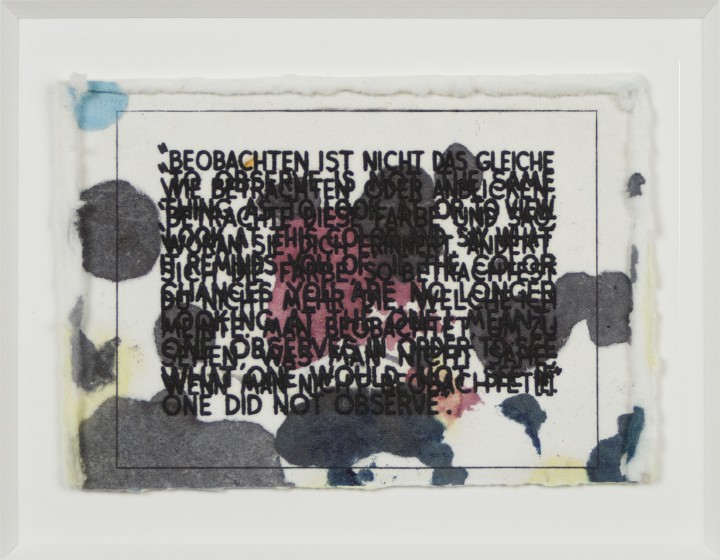

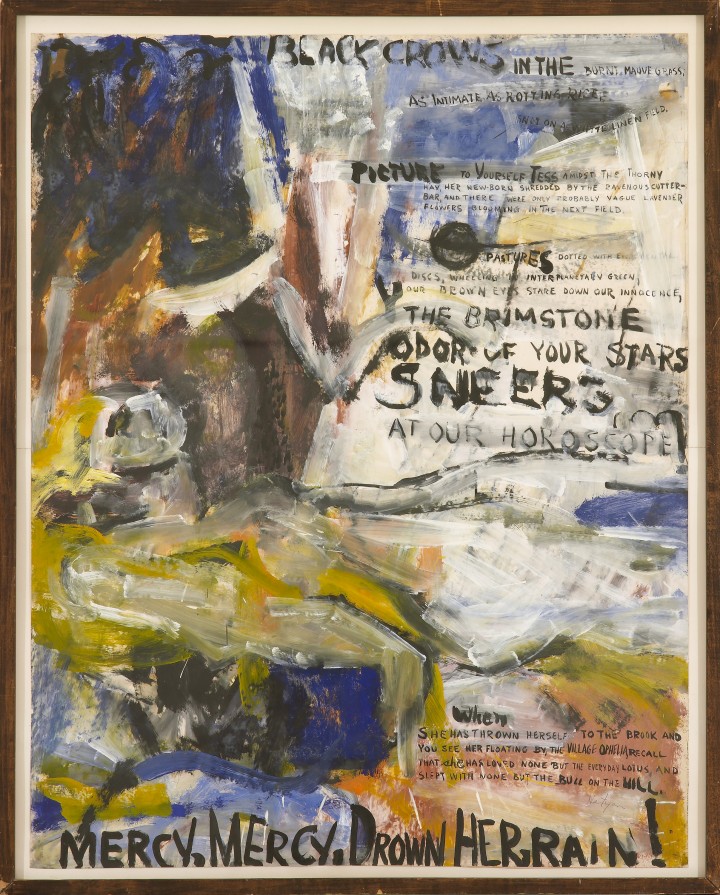

Perhaps the most striking thing about Grace Hartigan’s Black Crows (Oranges No. 1) (1958) is the tension between the gestural surface and the phrases that emerge from the background of the work, at times overtaking the paint. A busy abstract surface is characteristic of Hartigan’s style, but whereas in much of her other work she allows imagery to form, here Hartigan intersperses her painterly strokes with selections of text taken from Frank O’Hara’s “Oranges No. 1.” The poem is one in a collection of twelve published in 1949 by O’Hara, in response to which Hartigan produced twelve canvases, each featuring excerpted text from the corresponding poem.

One of the defining traits of Abstract Expressionism was the emphasis put on immediacy, and Hartigan’s gestural abstractions are a product of this era. In a parallel vein, O’Hara is known as a master of occasional poetry—the kind of thing jotted down on a cocktail napkin at a party just before a toast is to be given. His ability to infuse language with an acute sense of immanence and a breadth of emotion strikes a similar chord to that of Hartigan’s urgency. Close social and intellectual relationships between painters and poets during any given period have often proven professionally fruitful for both parties. The post-war period is particularly notable for a proliferation of these intimacies and the resulting work that grew out of them.

A 1957 poem by O’Hara entitled “Why I Am Not A Painter” opens with the lines, “I am not a painter, I am a poet. / Why? I think I would rather be / a painter, but I am not.” O’Hara goes on to describe working on his “Oranges” poems while his friend, the painter Michael Goldberg, works on a painting called Sardines (1955). As O’Hara tells it, both artist and poet begin with a word that serves as the title, but which does not figure prominently—or at all, in O’Hara’s case—within the finished work. This poem speaks to the close relationship between painter and poet, enumerating similarities in their intellectual approaches to their practice, while also making clear how these two artists, working in two mediums, ultimately produced two very different works.

O’Hara’s poem articulates the difference between painting and poetry as having to do with expressivity: “All that’s left is just / letters, “It was too much,” Mike says. / But me? (…) / There should be / so much more, not of orange, of / words, of how terrible orange is / and life.” O’Hara brings the tension between too much and not enough into the same field, suggesting that duality and contradiction are central to expressivity. By exploring the different valences of language across painting and poetry, we come to understand that though the two differ in some medium-specific ways, there is no hard and fast distinction between them. As often as difference is brought to bear as a way of producing hierarchies of value, when examined closely, it is not always so black and white.

Black Crows (Oranges No. 1) can be understood as a continuation of the conversation begun by Goldberg and O’Hara. Hartigan processes O’Hara’s poetry by augmenting the dimension and shape of the words, such that they seem to undulate with the flow of paint in three dimensions. Whereas O’Hara, in crafting a poem about difference, folds in Goldberg’s language relating to his own practice, Hartigan brings language out of O’Hara’s work and into the painterly realm. In Hartigan’s hands, O’Hara’s words become visually expressive in a manner more akin to painting than to poetry. The resulting painting, like O’Hara’s poem, works the divide between visual art and poetry, demonstrating difference while simultaneously showing the tenuousness of any distinctions that can be made.

Grace Hartigan

Cat Dawson