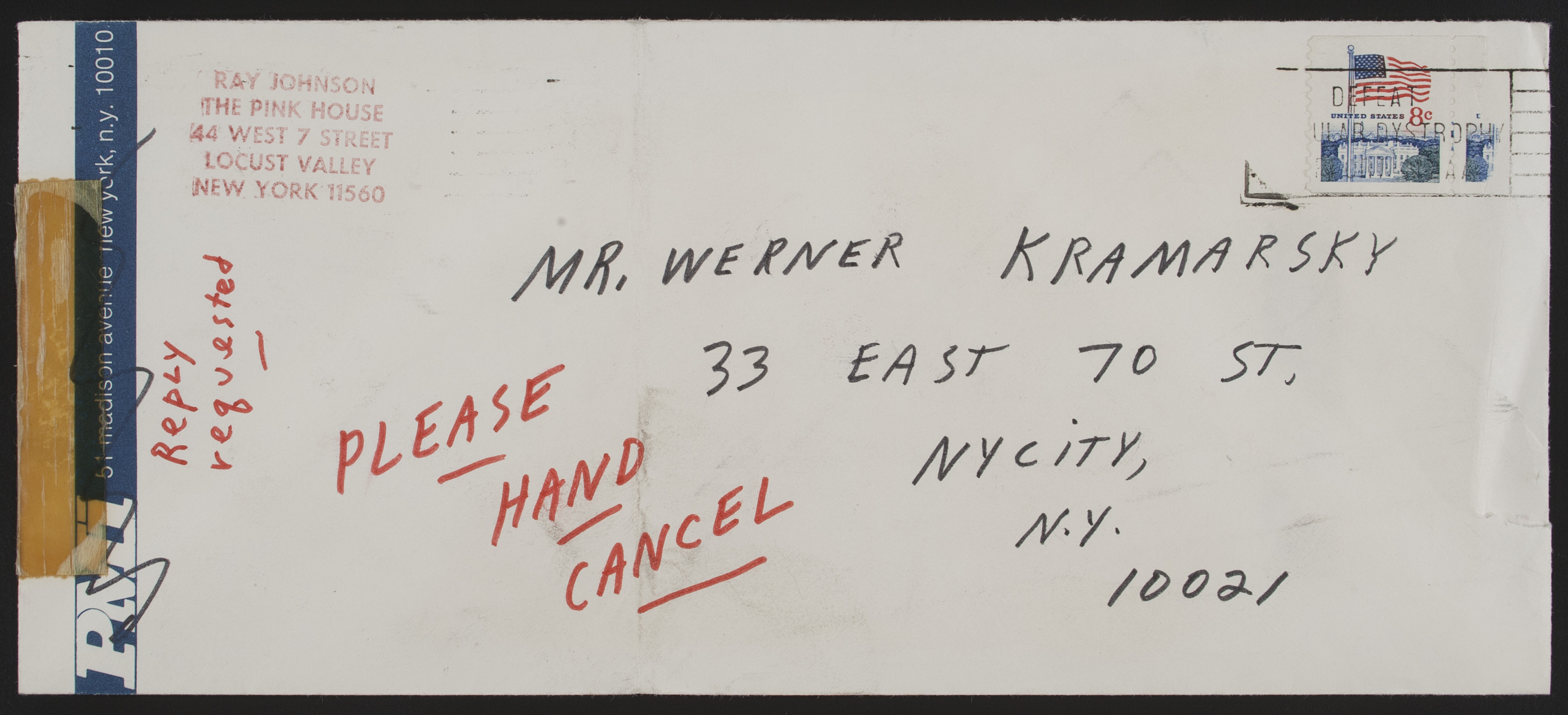

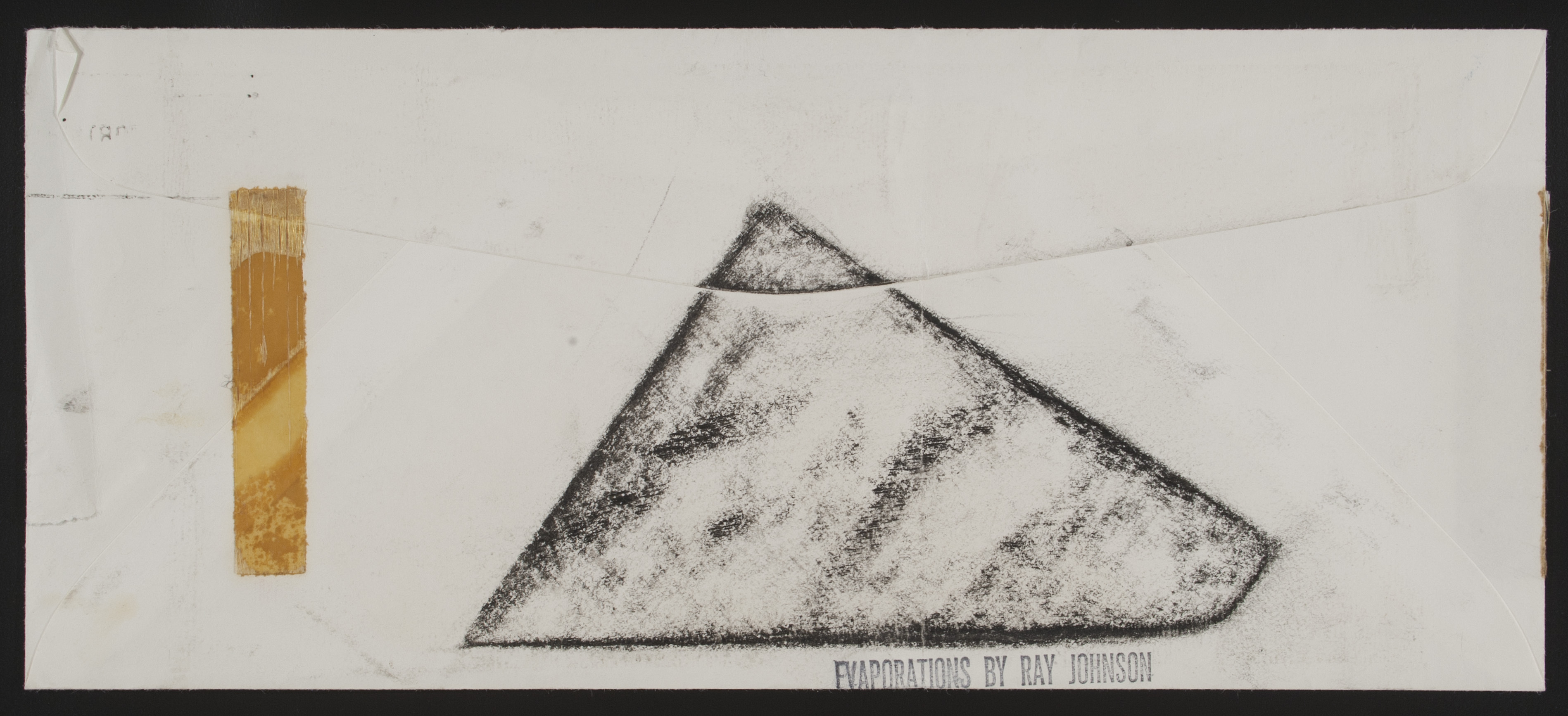

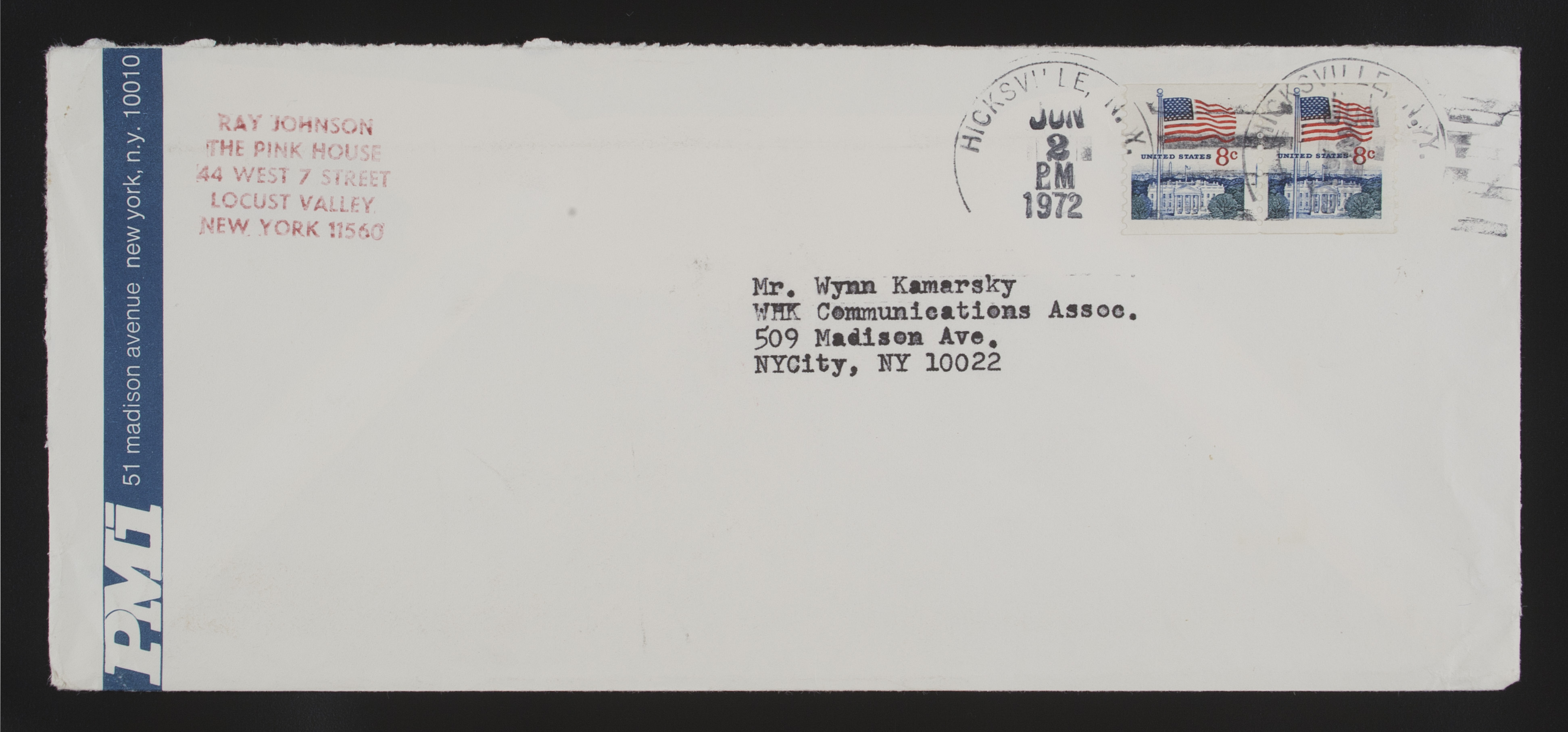

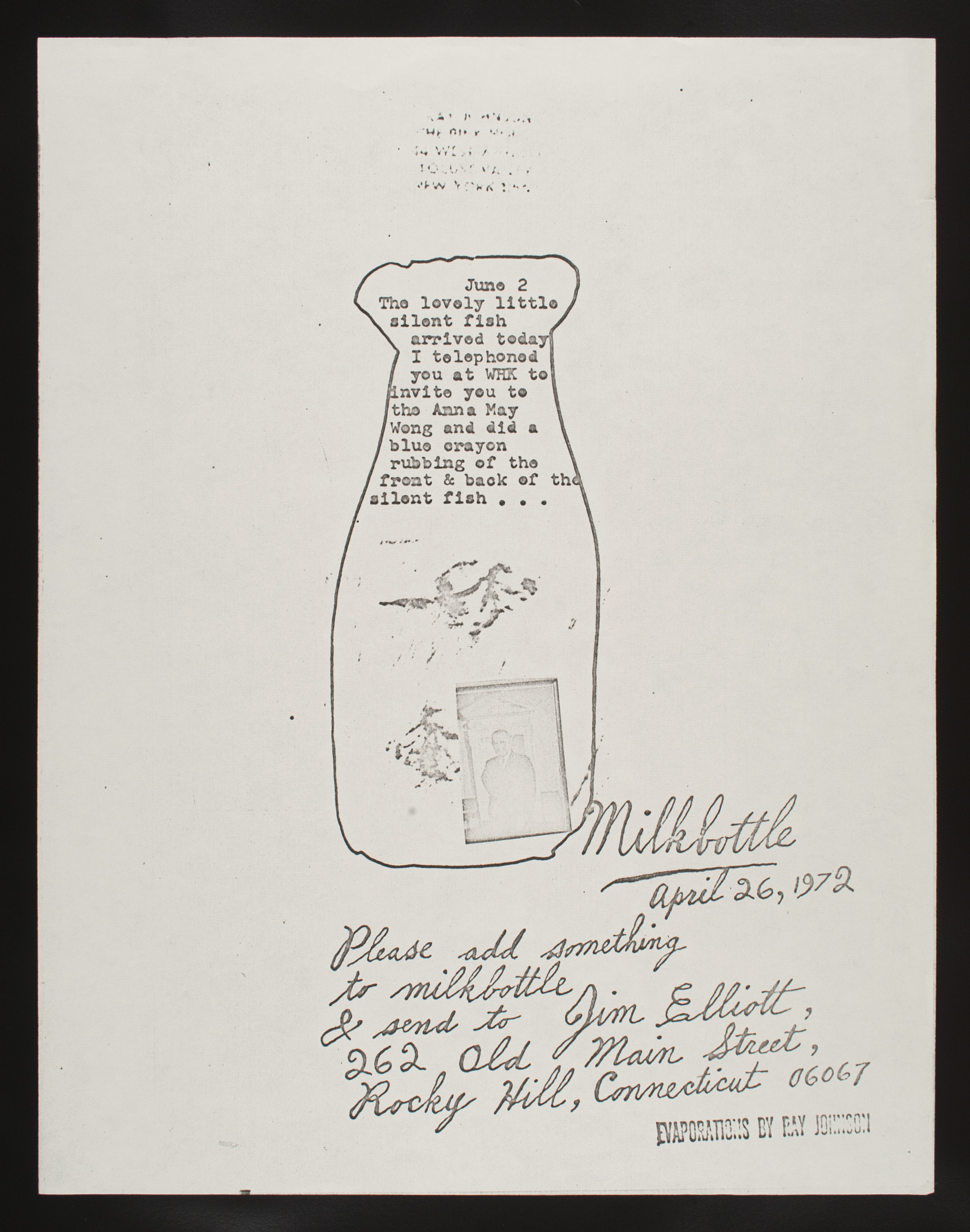

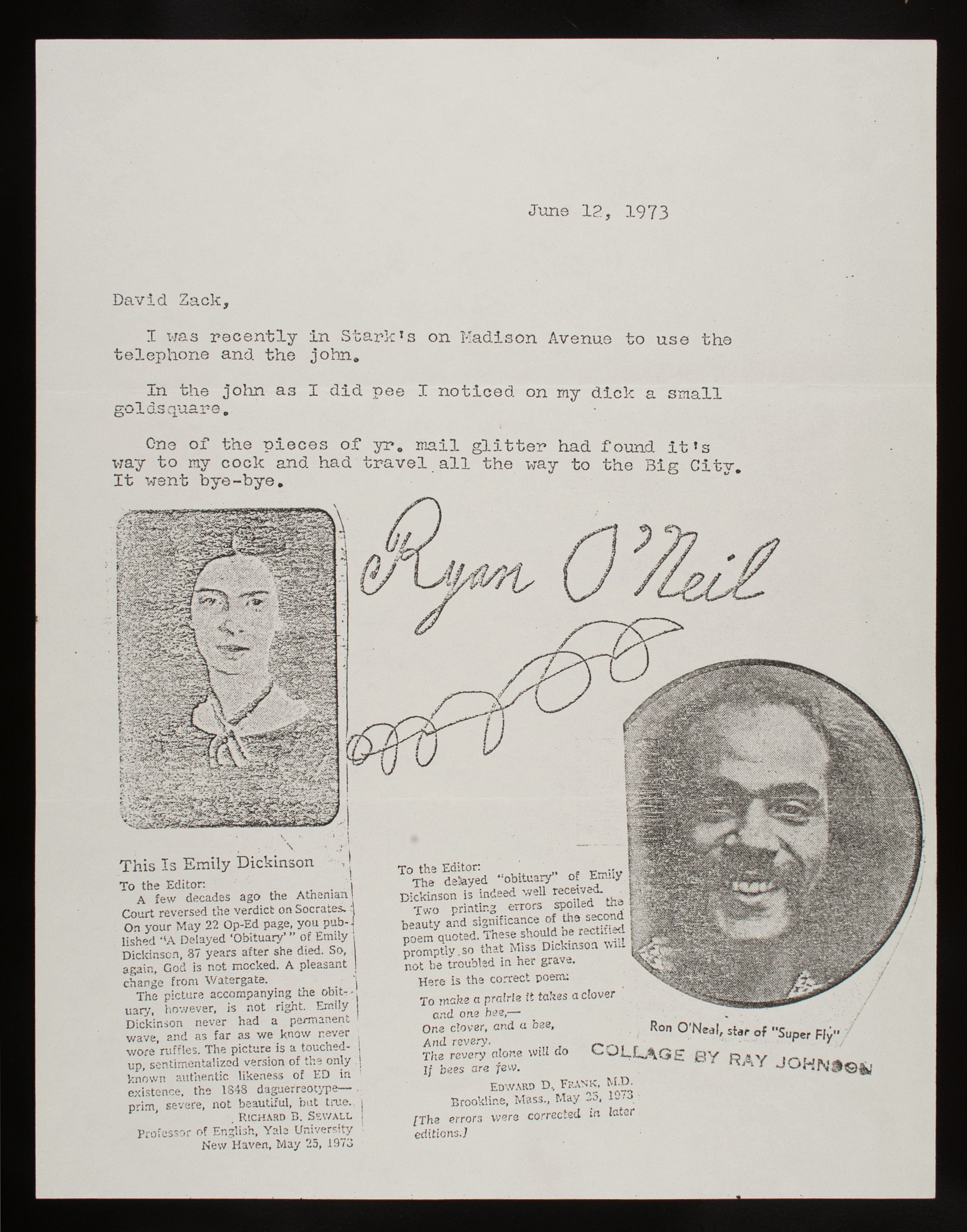

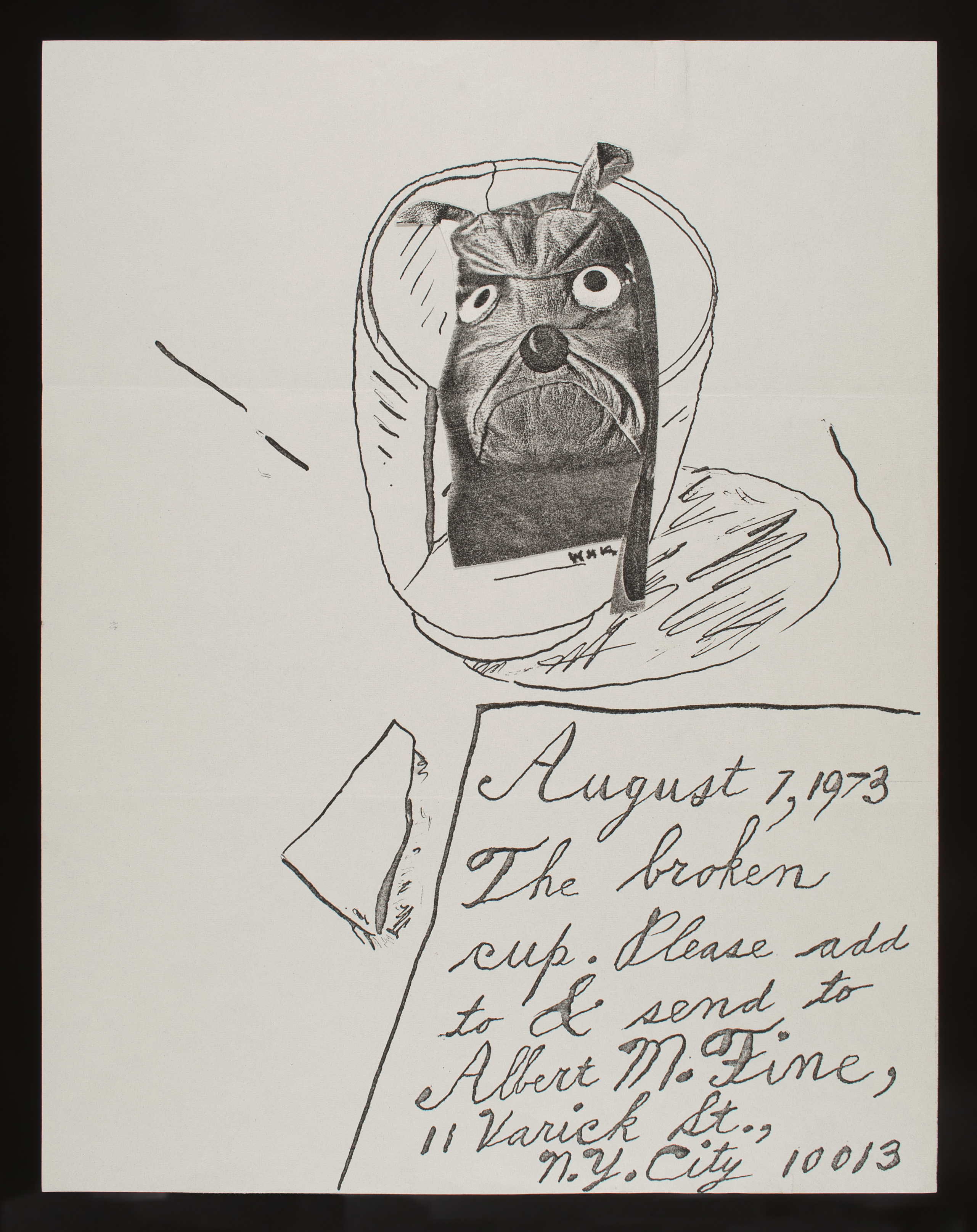

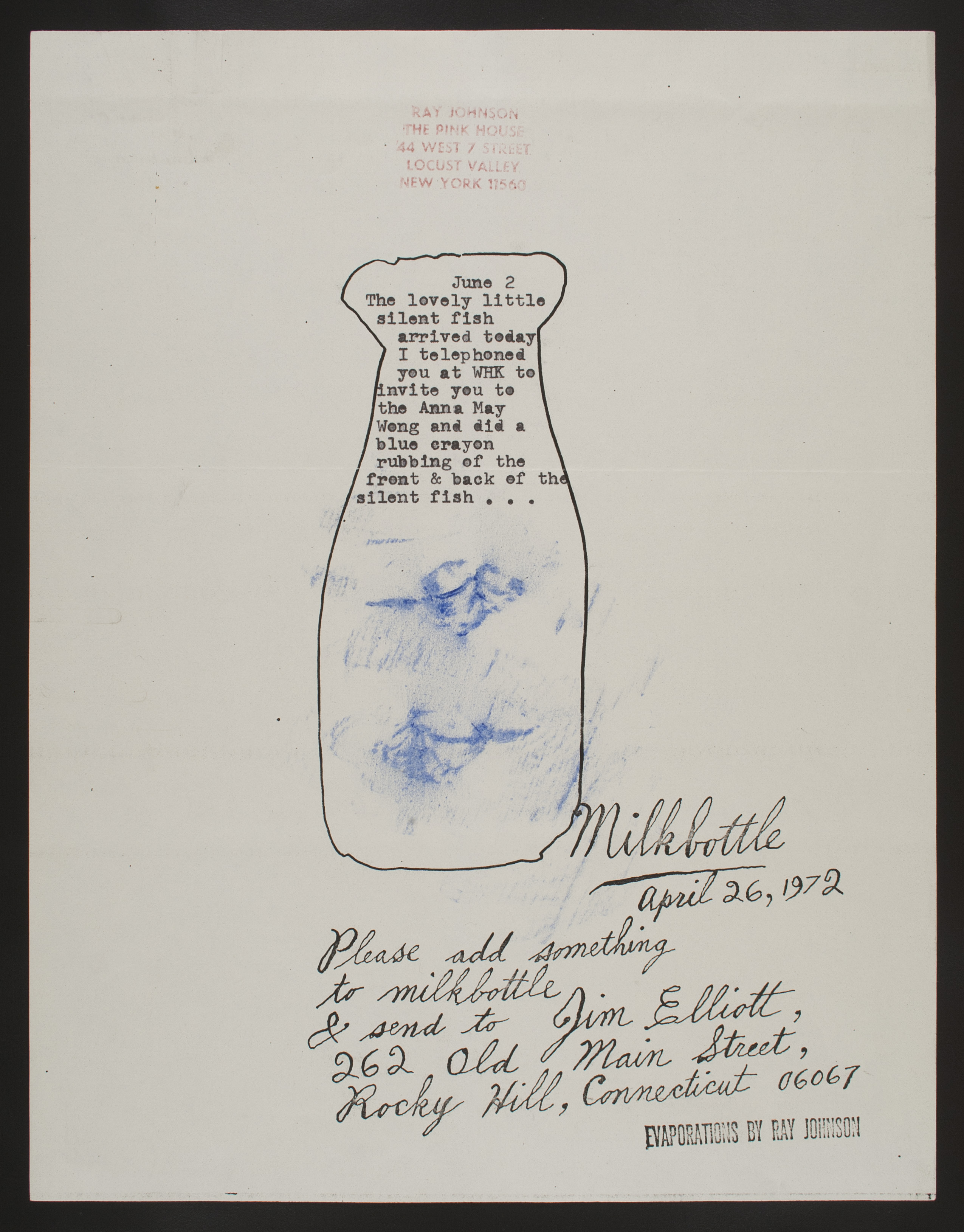

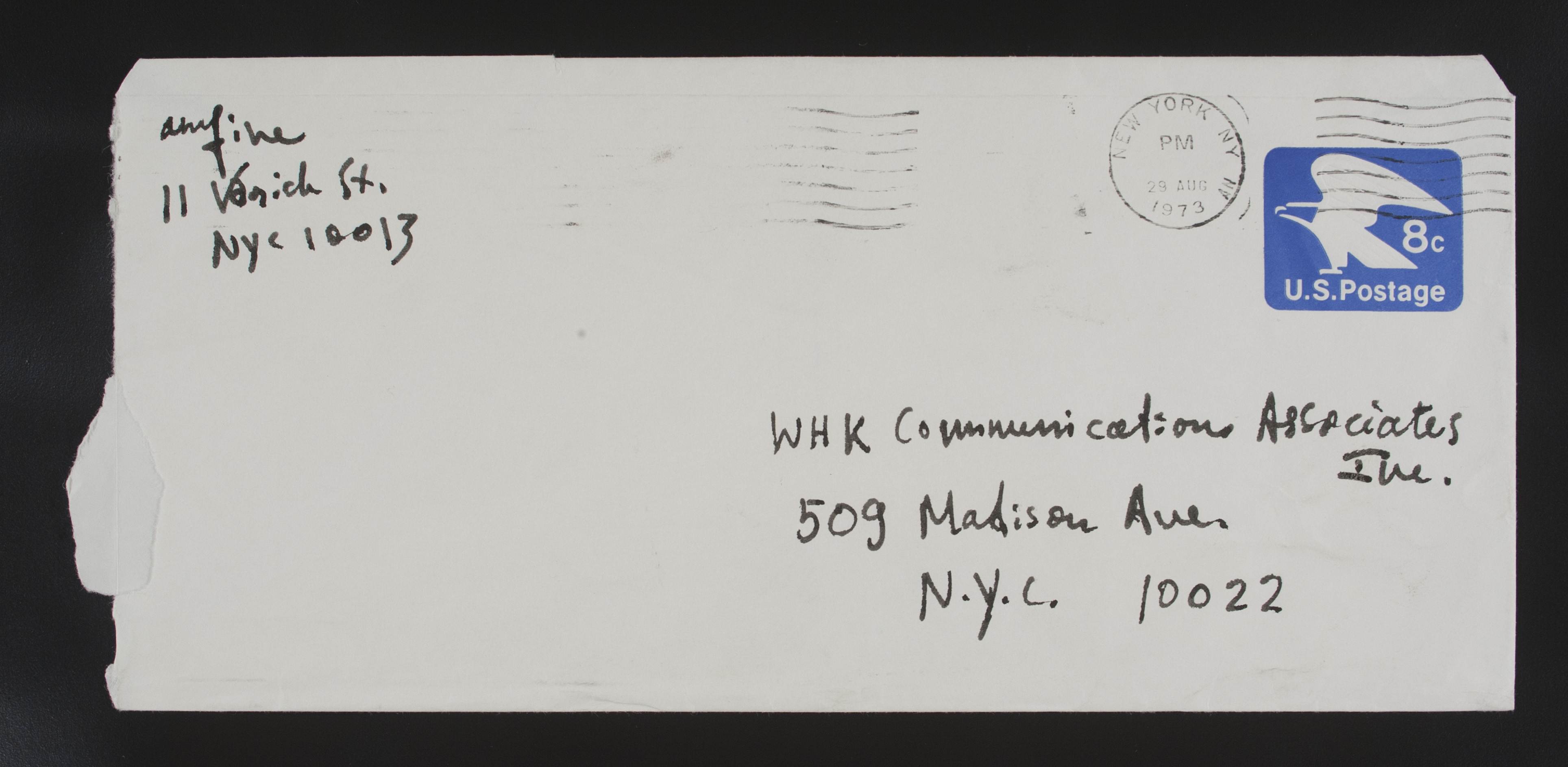

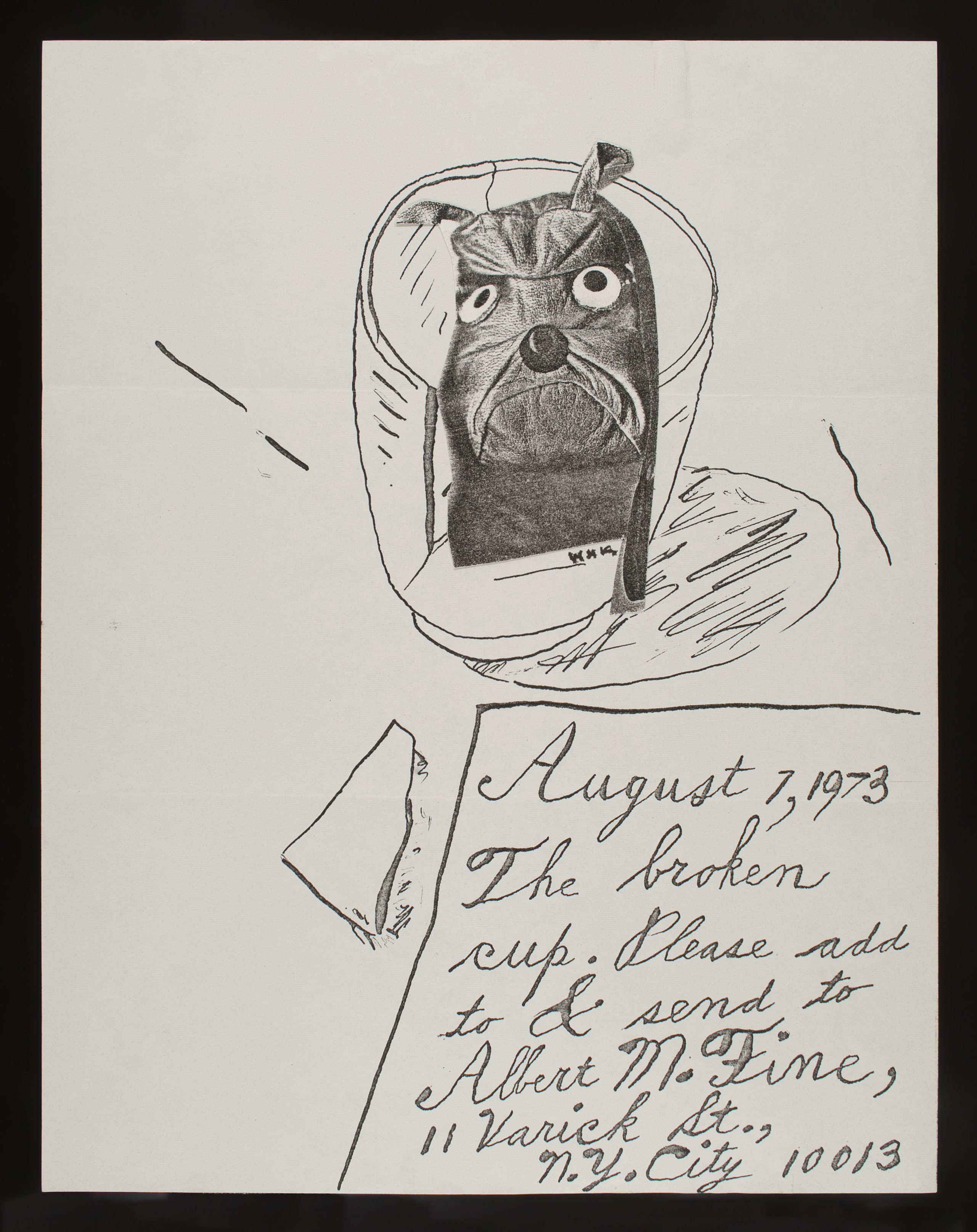

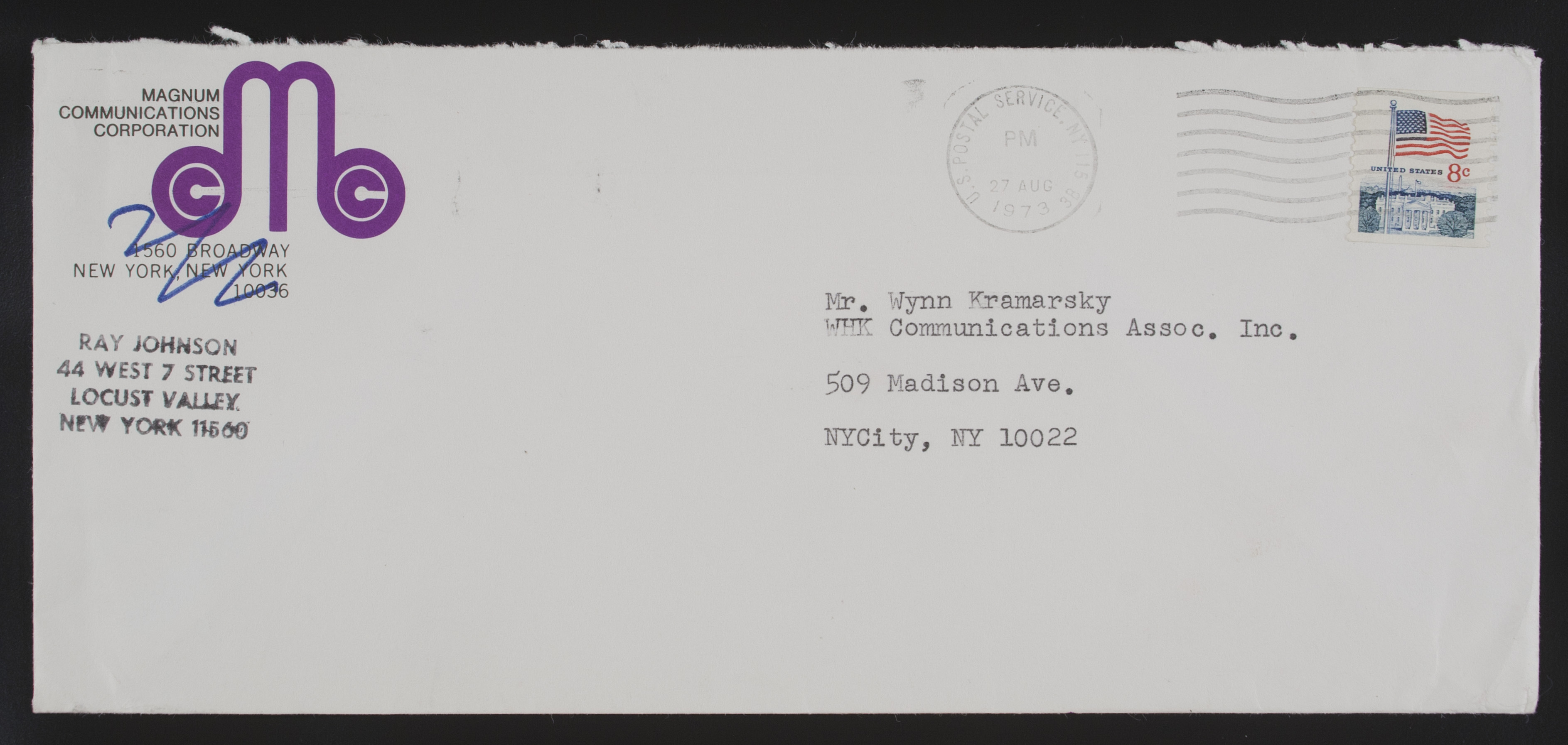

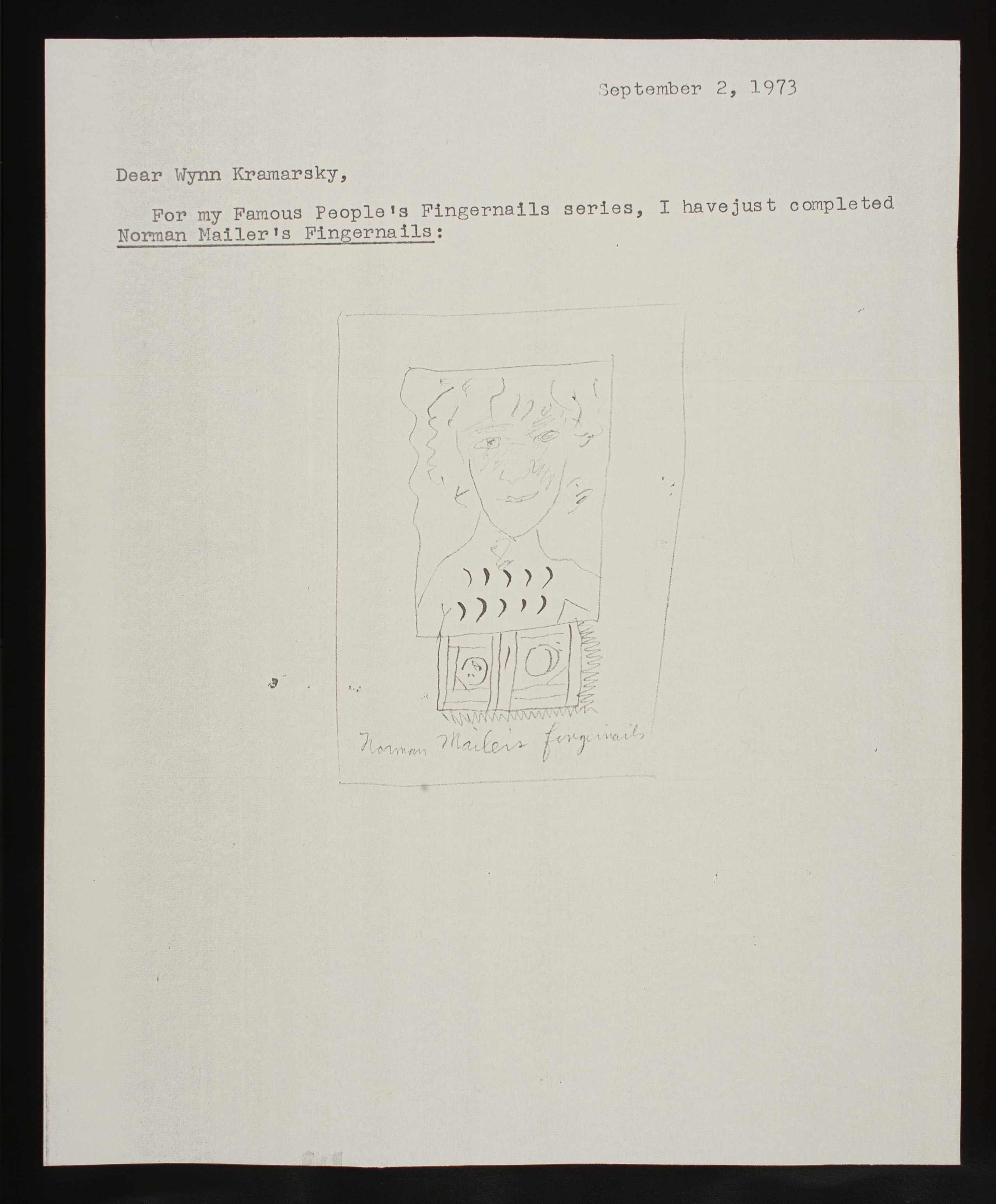

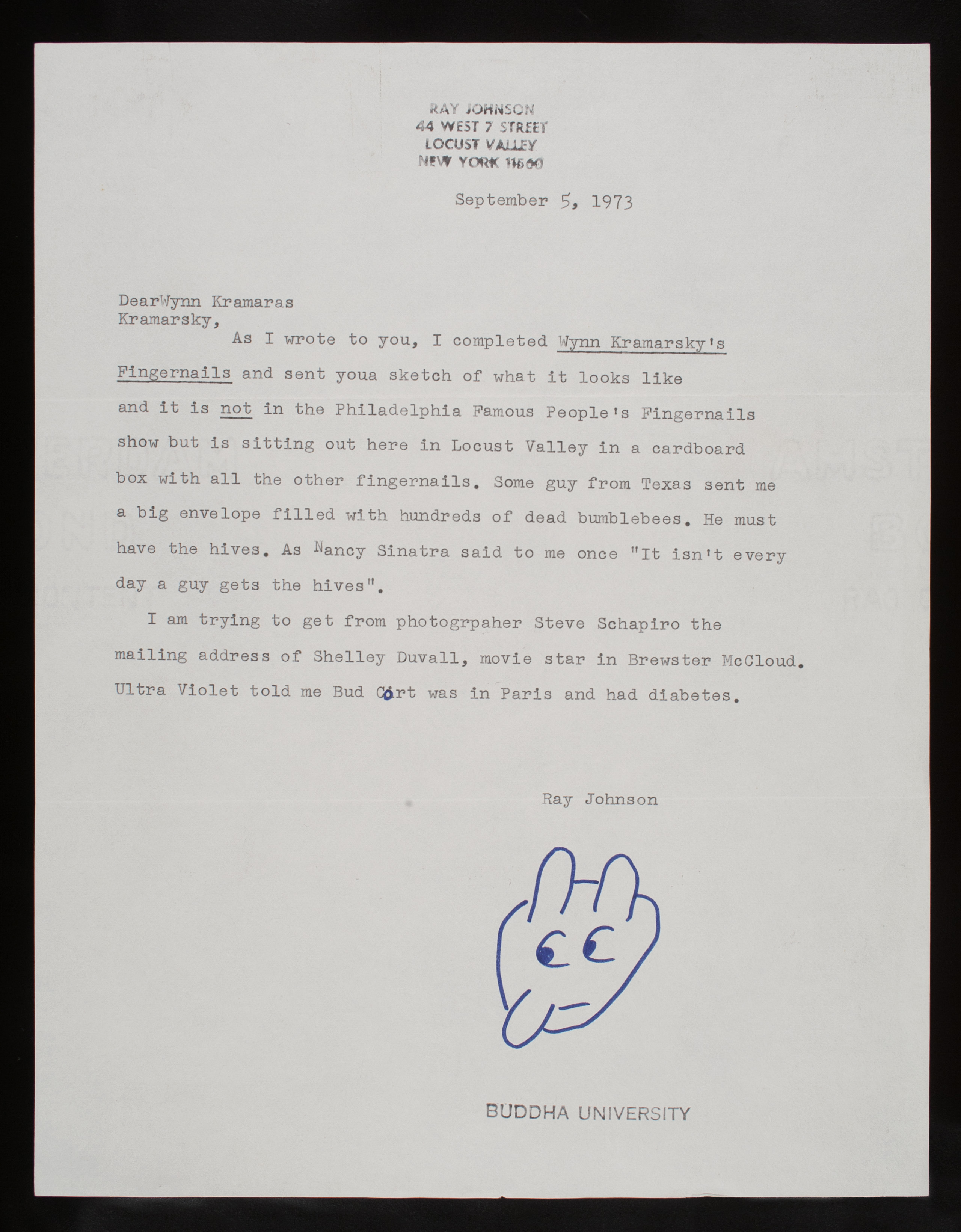

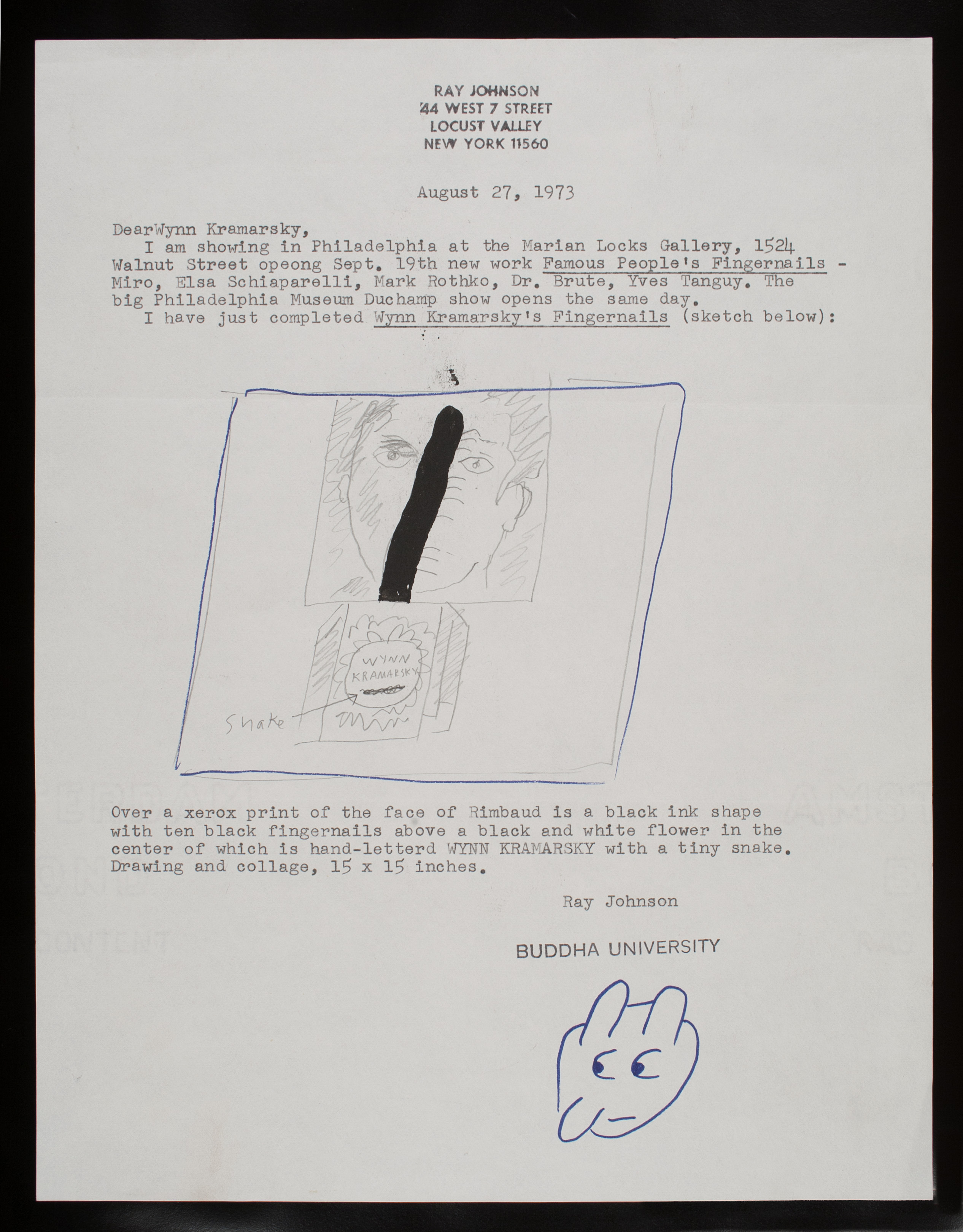

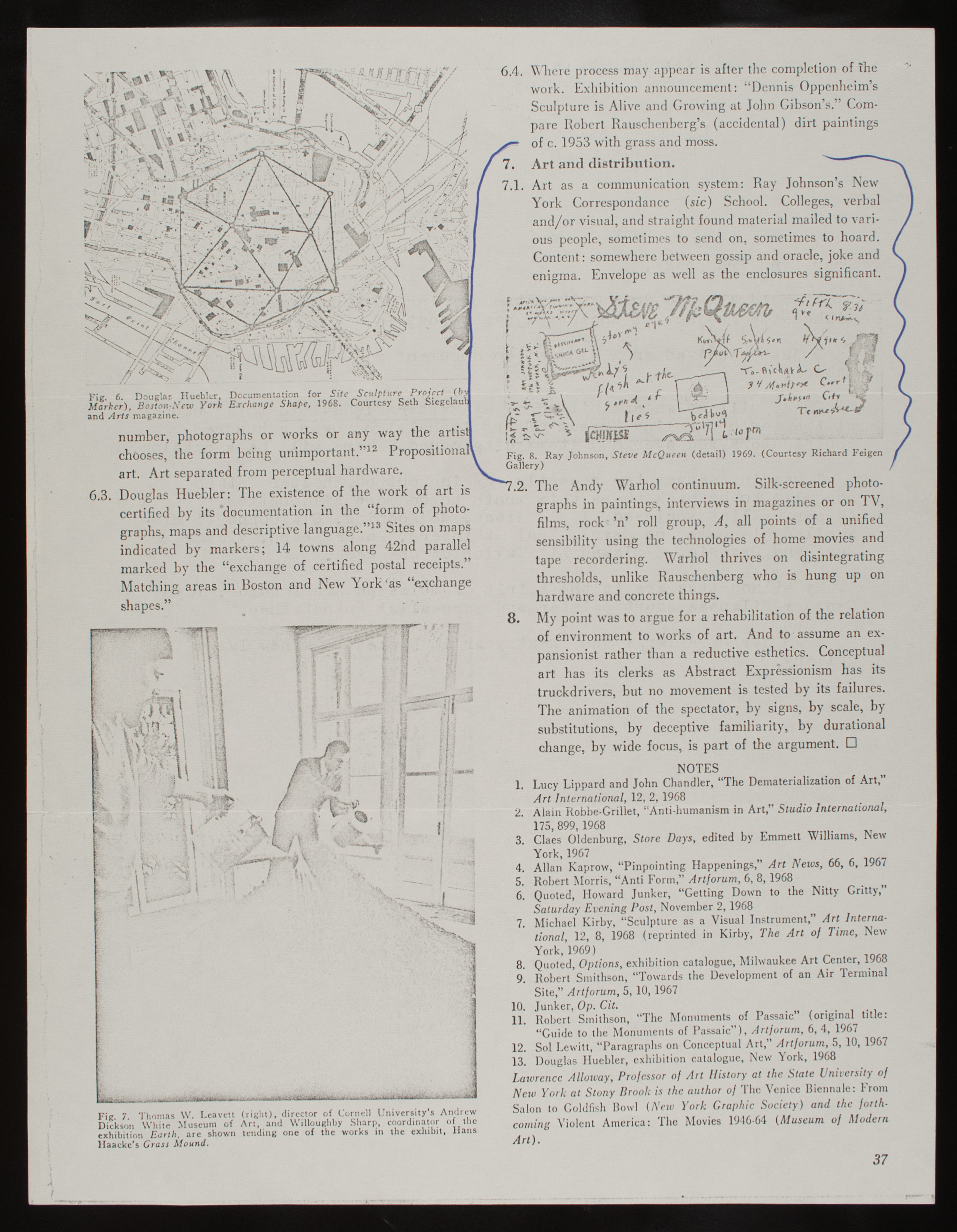

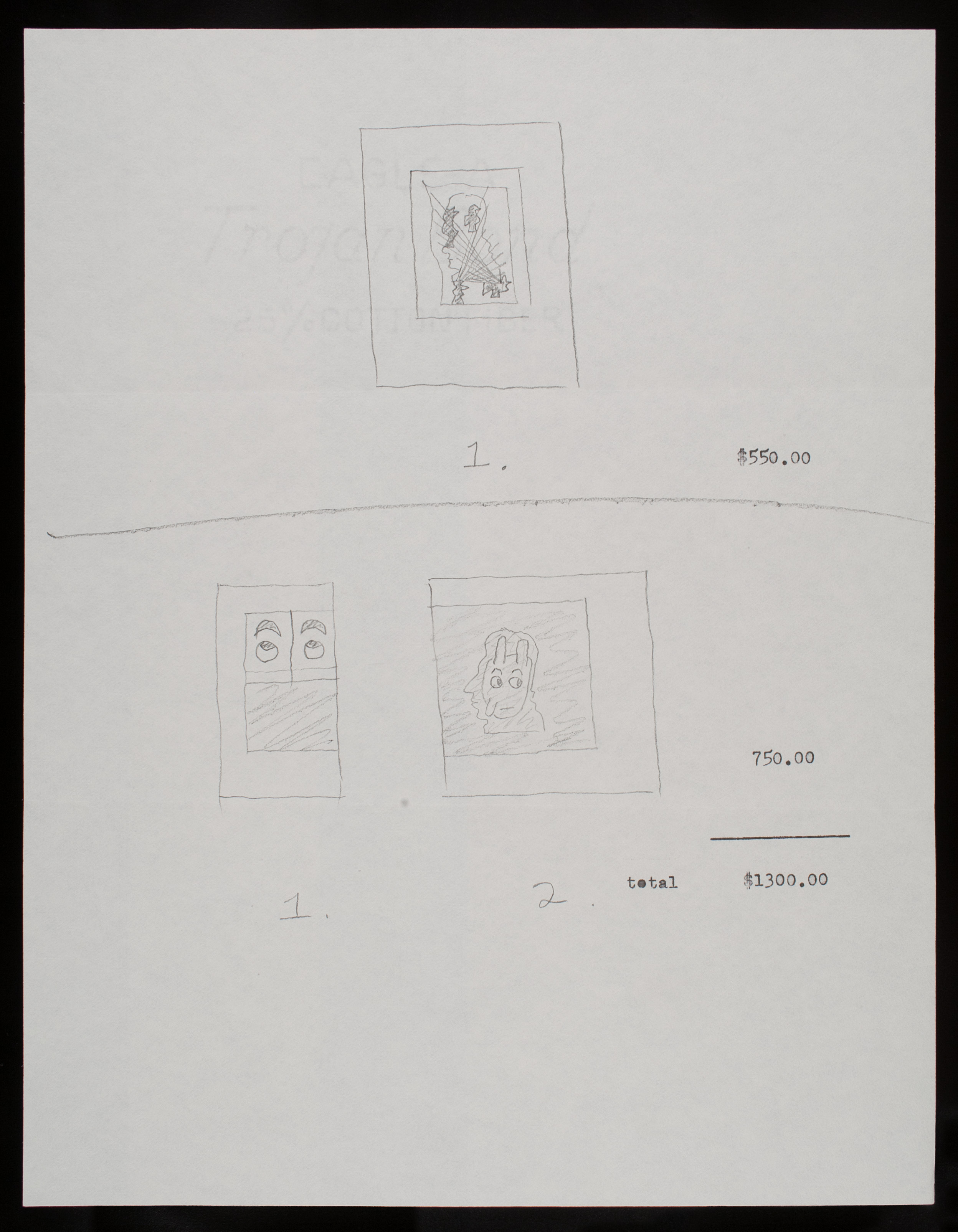

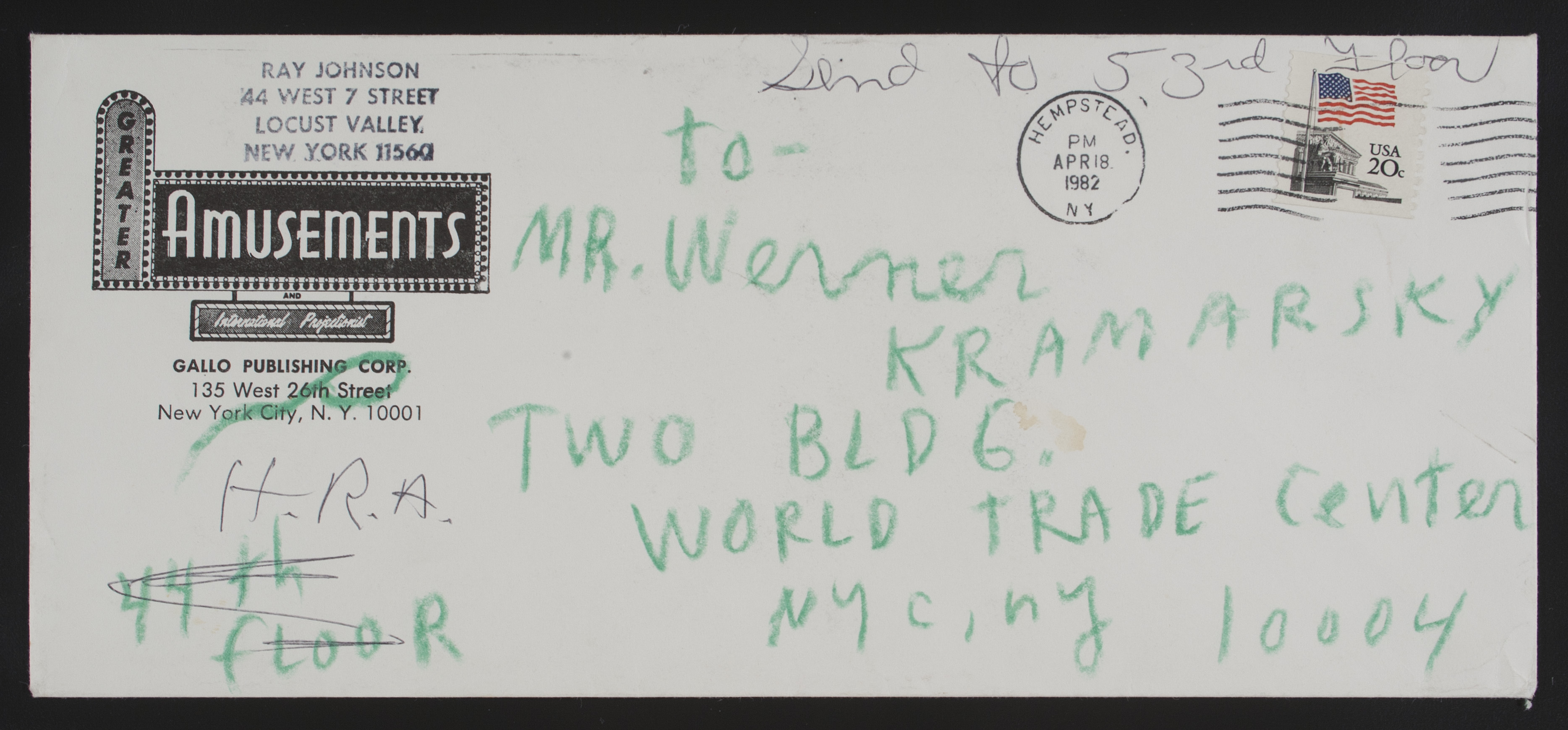

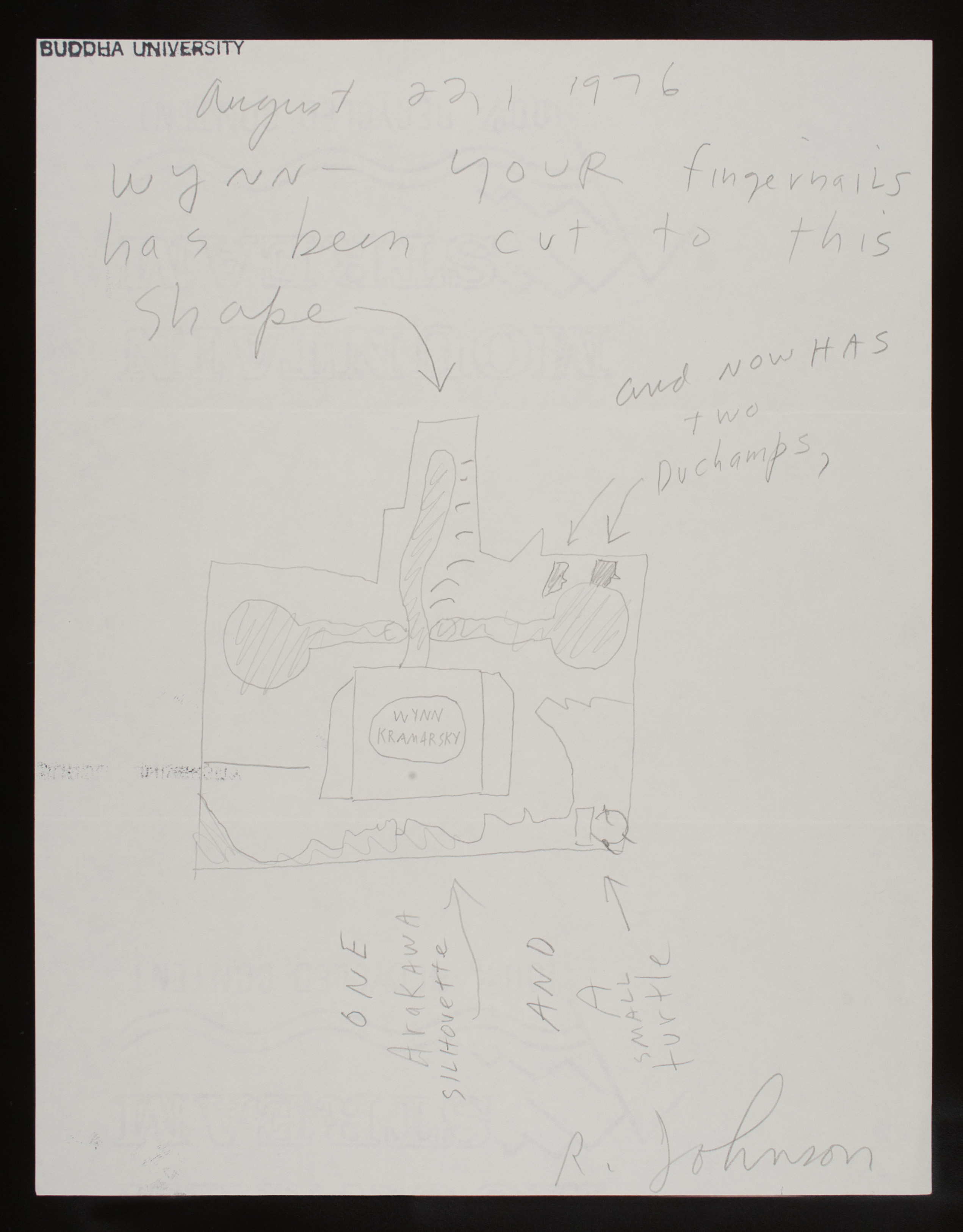

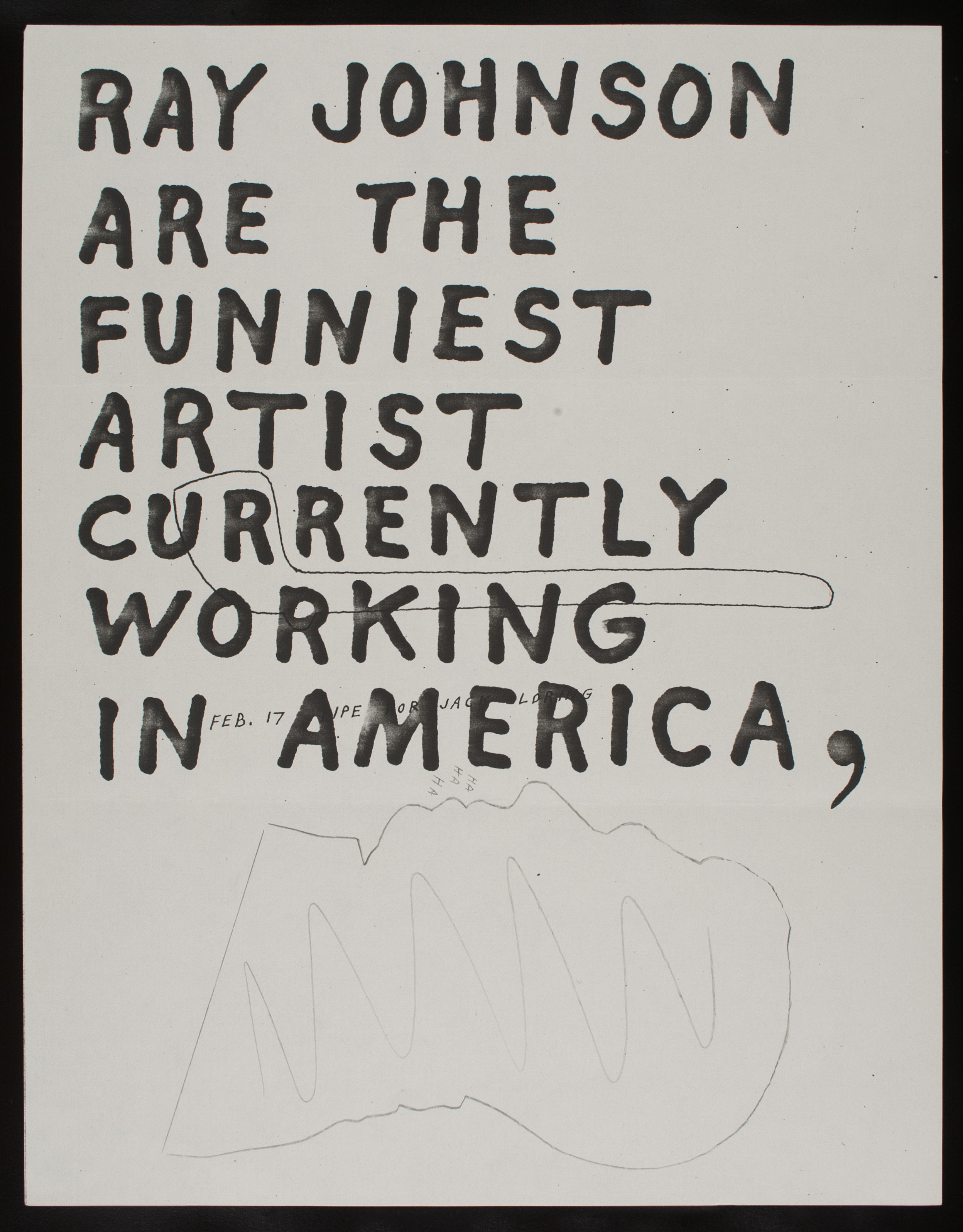

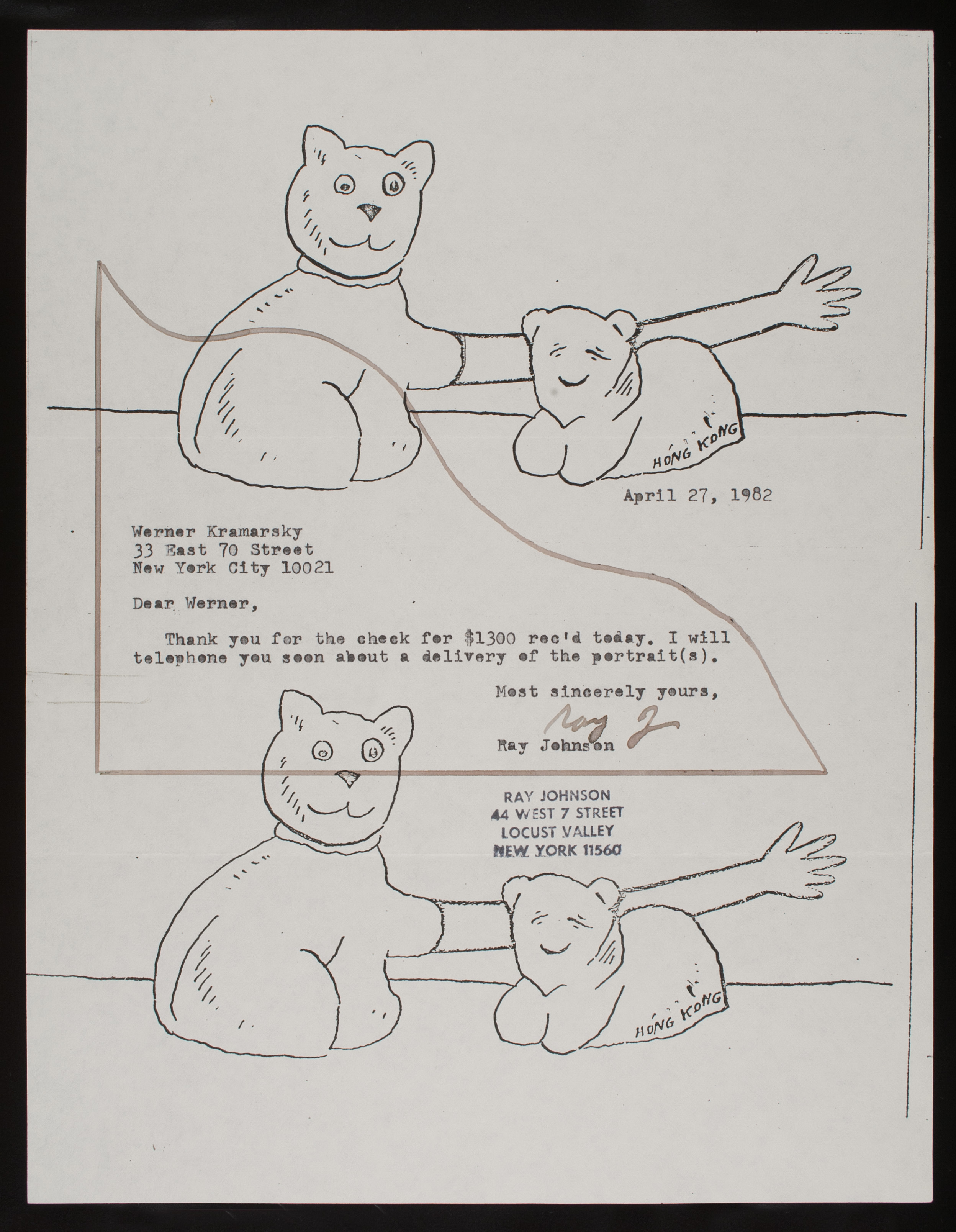

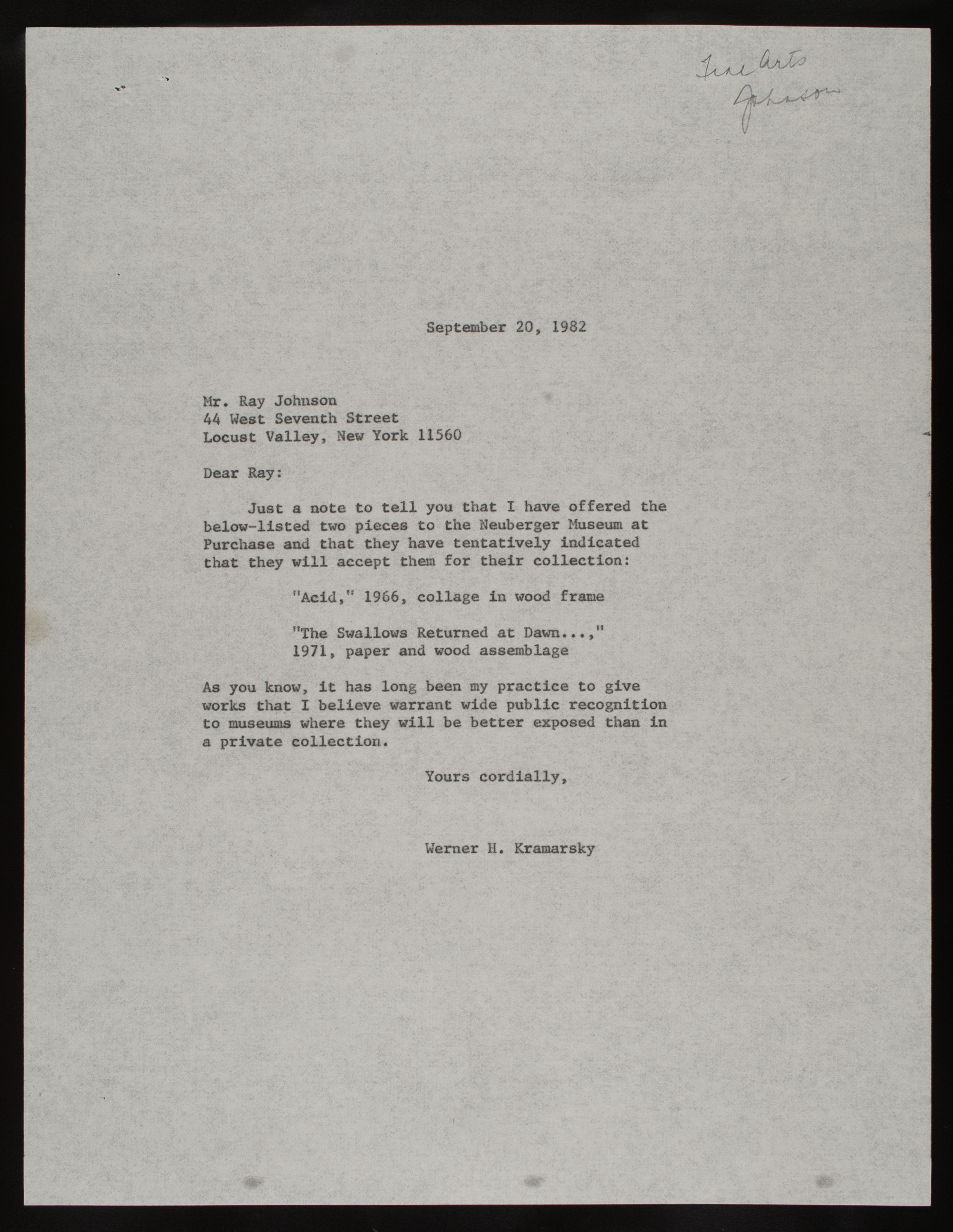

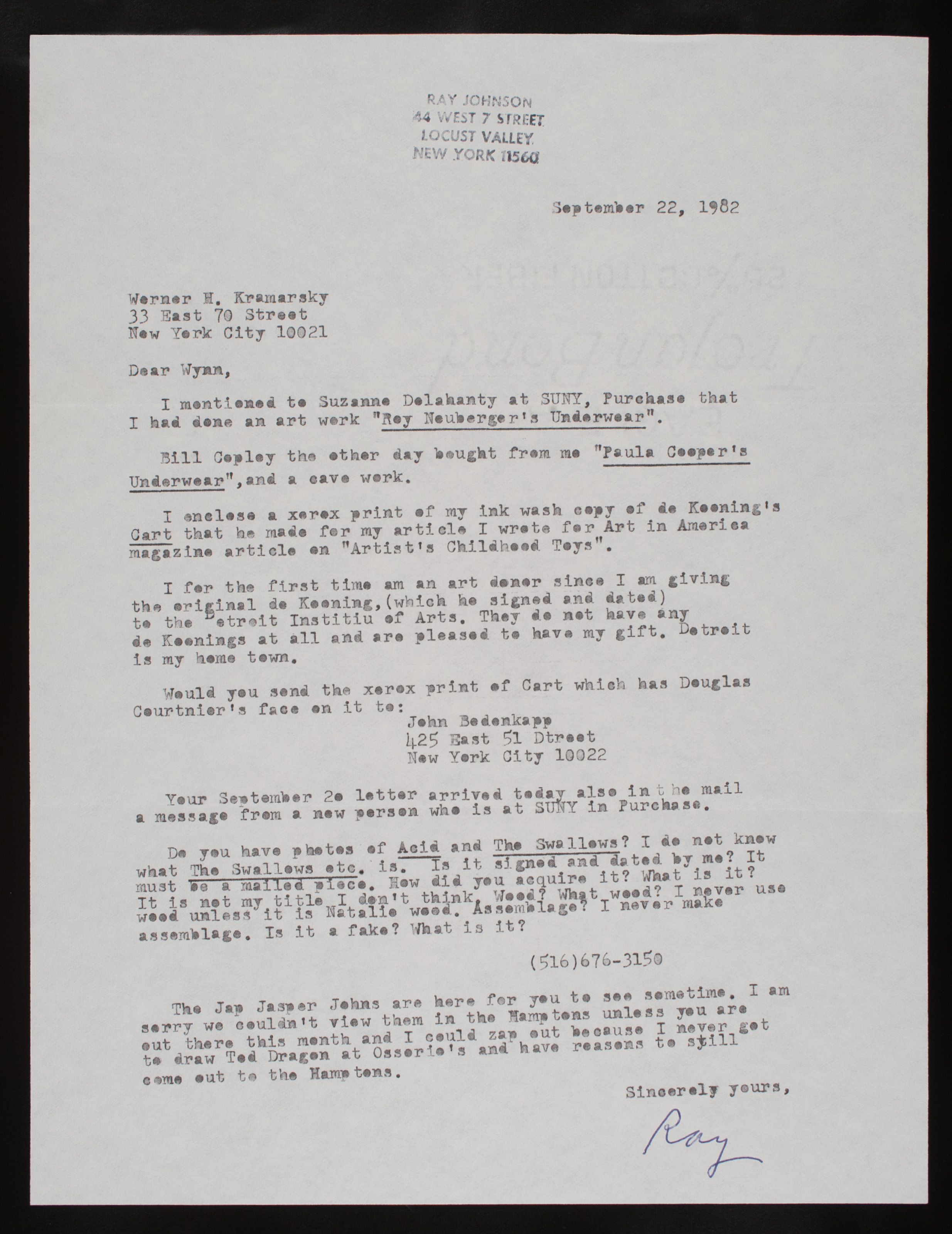

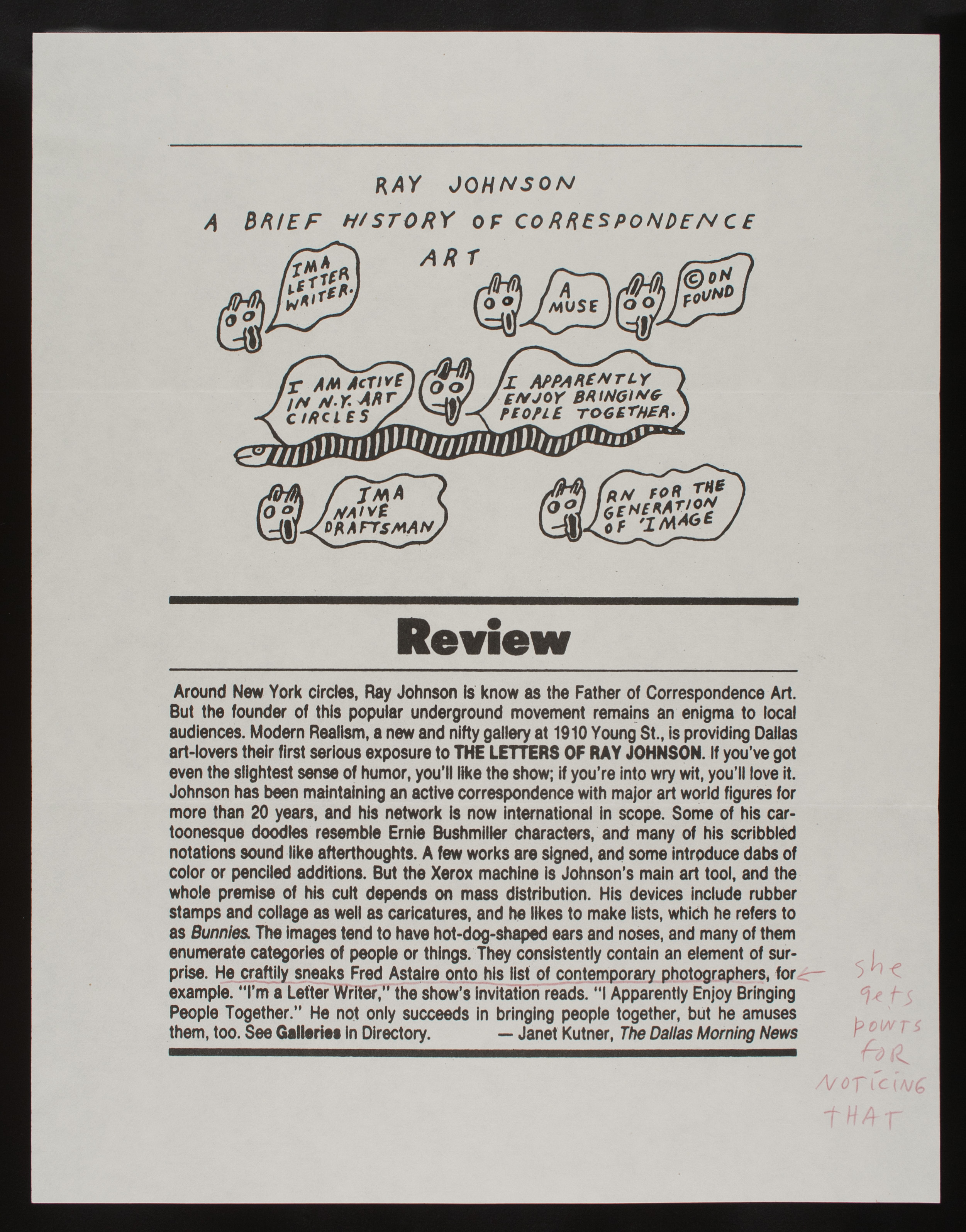

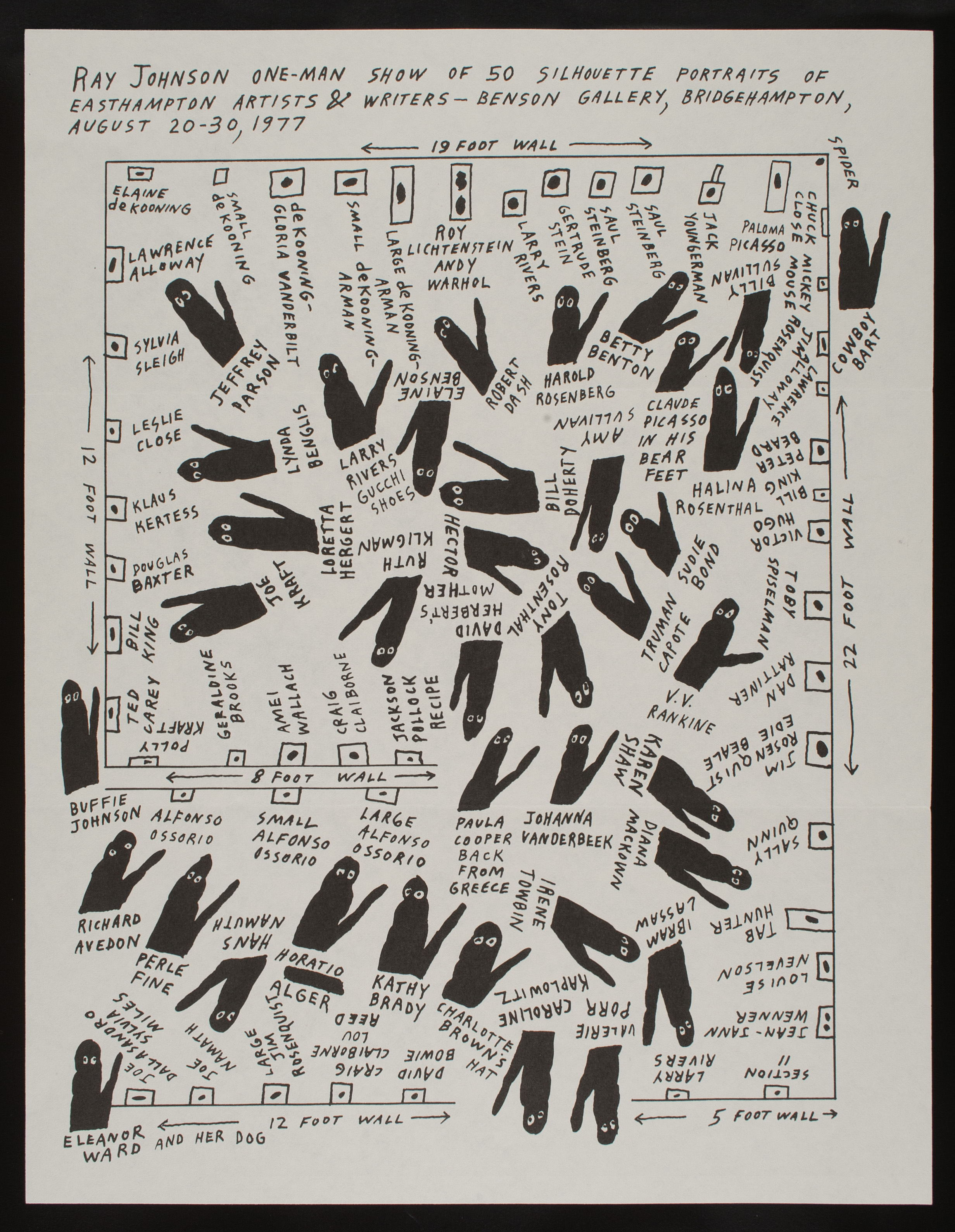

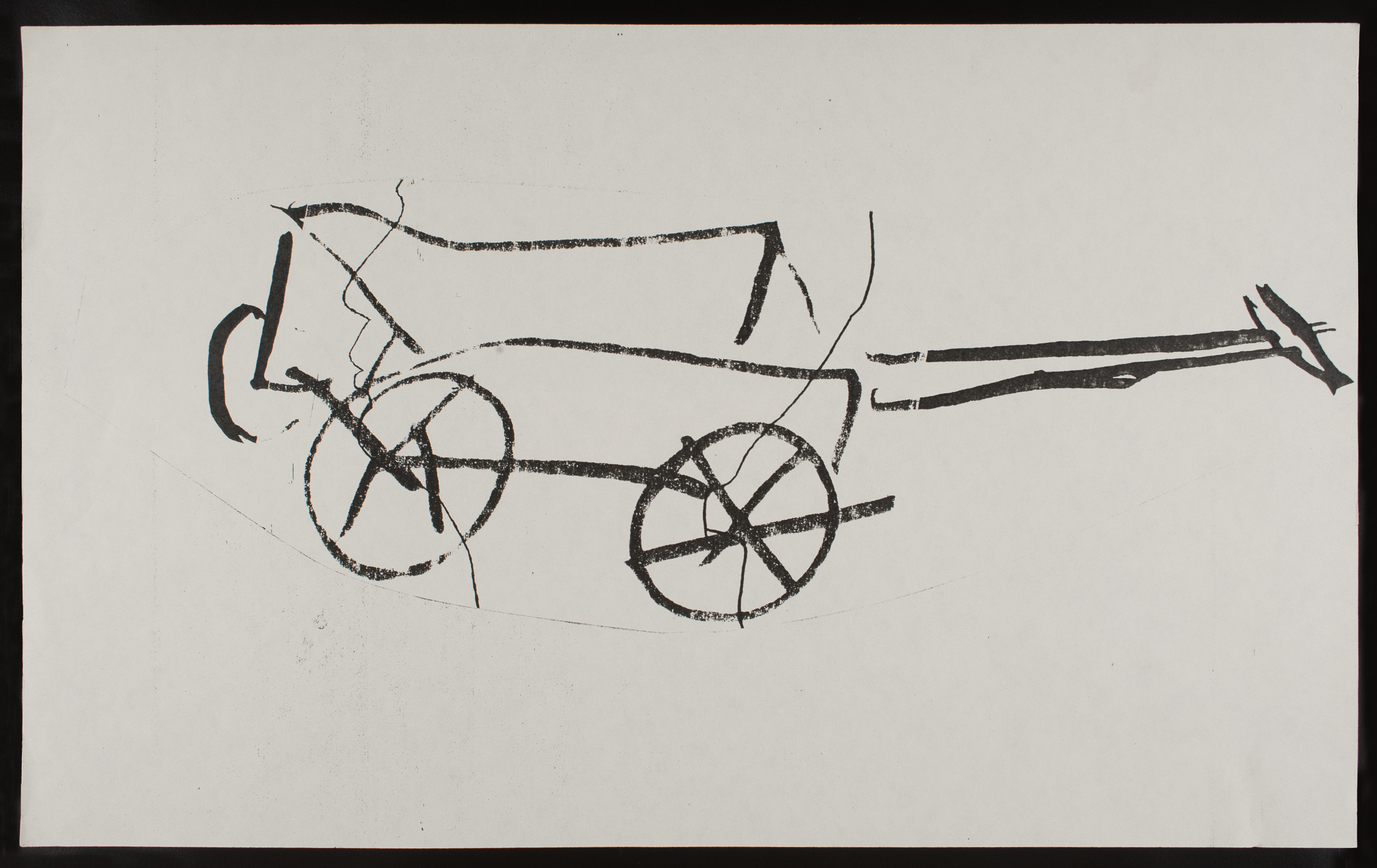

Ray Johnson, Correspondence Archive, 1972-1994, mixed media on paper, dimensions variable. © Wynn Kramarsky & Ray Johnson Estate, Courtesy Richard L. Feigen & Co. / Photo: Ellen McDermott

Fever Dream about Ray Johnson

It seems like everyone has a story about Ray Johnson. I also have a story about Ray. It’s not a story in the traditional sense–not a “One time, Ray and I…” sort of story–because he was long dead when I met him.

The context of my Ray Johnson story is that I was asked to write a fictional response to Ray Johnson. I had never heard of Ray before. But suddenly I was inundated with images of his work. And then something unexpected happened, which was that I got sick, and while I was sick, I had a dream about him. That’s my Ray Johnson story.

The dream, as dreams tend to be, was a collage. This one had five parts.

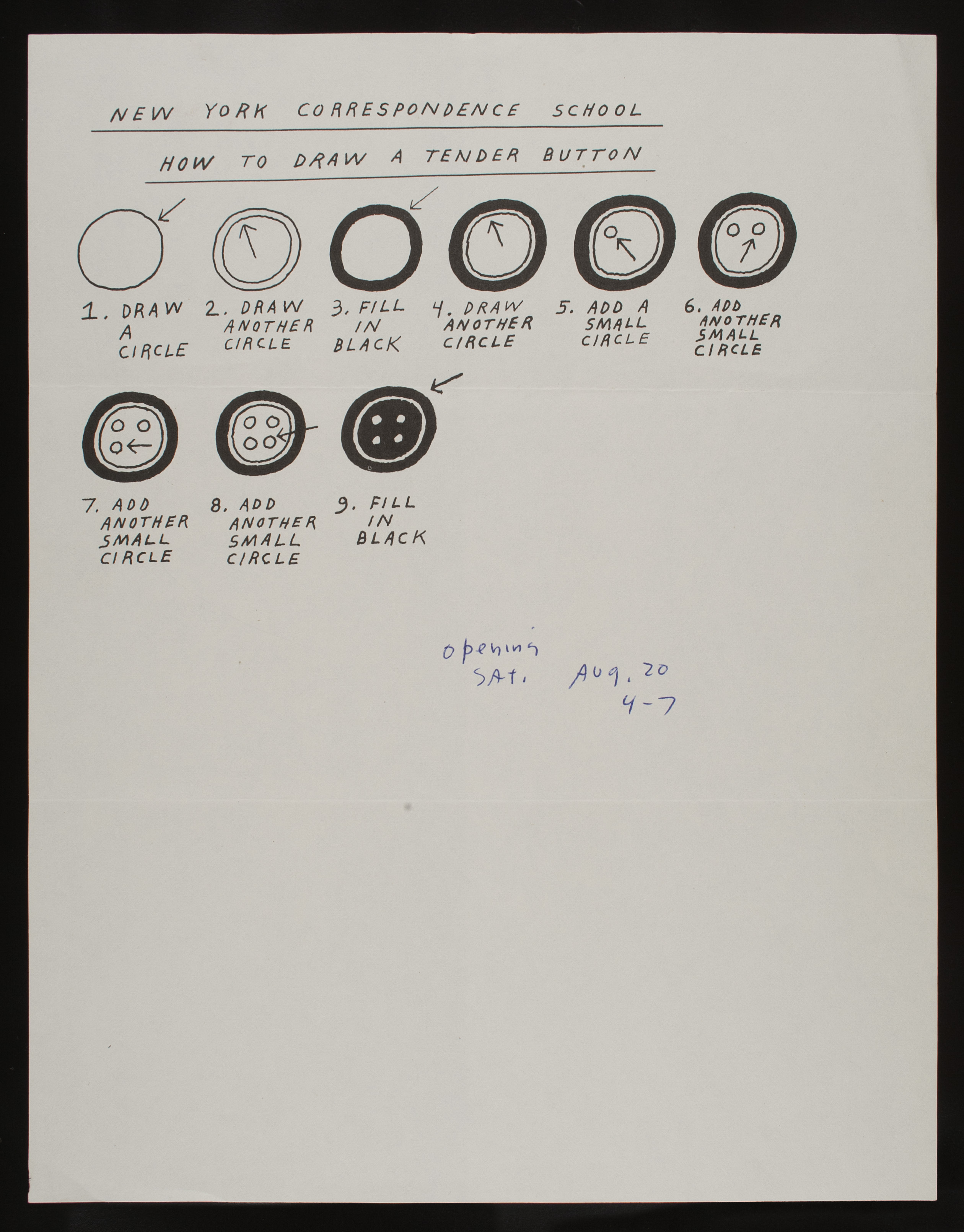

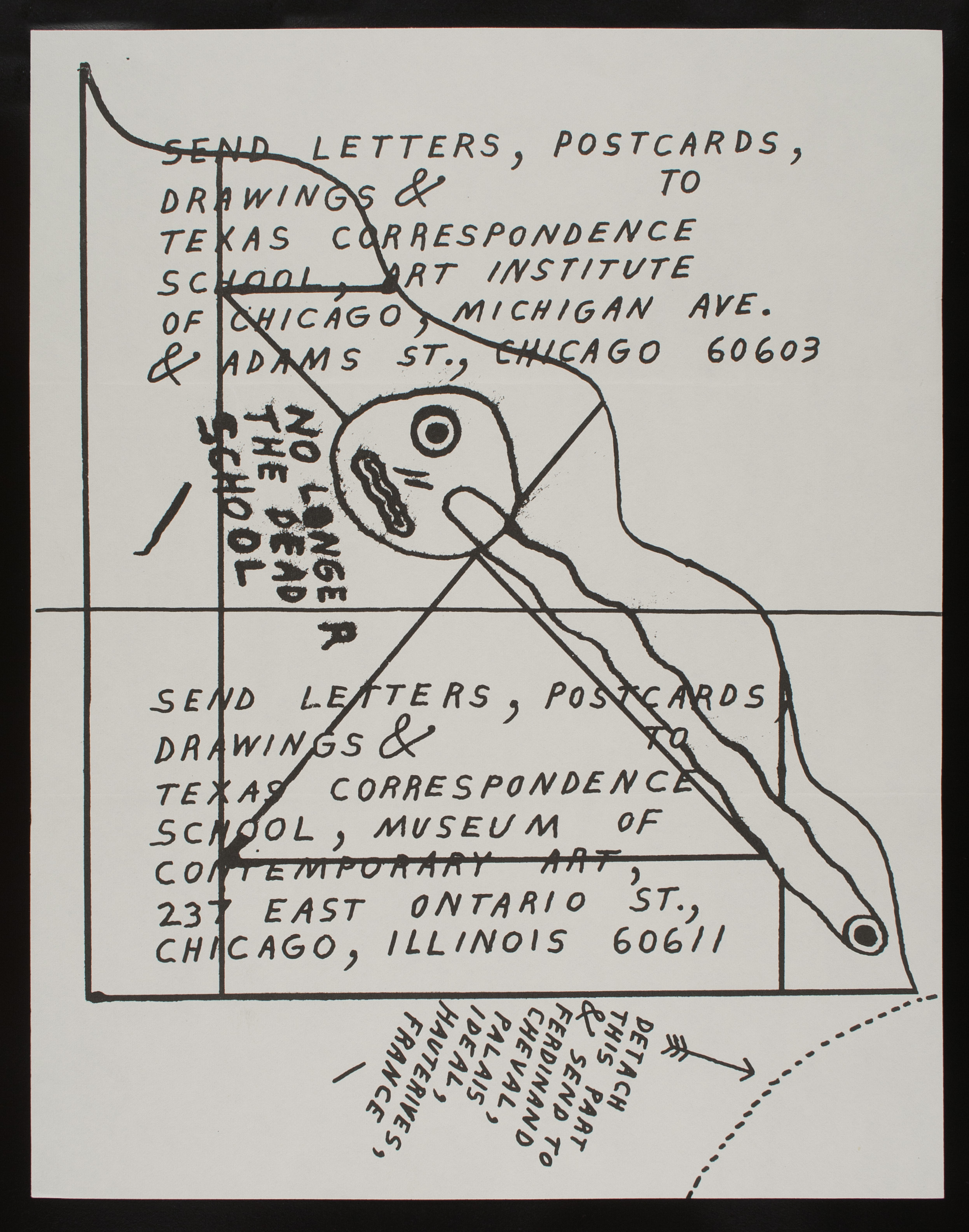

The Part with the School:

The dance class at the Correspondance School was called “Steps to Christ,” and the twelve steps were clearly diagramed on the chalkboard. I sat by the window because I wanted a view of the grass, and beyond the grass, a river with a bridge, and beyond the river, two peaks. (Later, I would see an envelope in an art gallery, elaborated by Ray with two bunny heads labeled “Himalaya” and “Heralaya.”) On every desk there was a nametag. I pinned my nametag to my chest, and my name was Art Baud. Ray arrived late. I knew his cue ball head from his picture, and his face–cheerful and sly as if he were wearing some kind of mask. He was twice the size of everyone. I couldn’t take my eyes off him. It looked like he’d gone swimming in all of his clothes. The teacher was waiting patiently with her hands folded on her desk; she wasn’t going to start her lesson until everyone was seated. The problem was that Ray was too big for any of the chairs. He was standing, trying to think of what to do. The tension in the room pulled the air taut. Finally, Ray lay across the whole back row of desks, and everyone cheered.

The Part with the River:

Instead of going on with the lesson, the whole classroom stood up (still cheering) and carried Ray out onto the campus quad, where the sun was shining and the birds were flitting over the grass. The grass gave way to the riverbank. Something about the quality of the day assured us a dip was going to be the perfect thing. We set Ray down next to the bridge, where lots of curious objects had washed onto the sand. Ray reached down and picked up a nutcracker in his huge hands and smiled, and then everyone stripped. I was soon surrounded by hundreds of naked celebrity artists, and I felt very self-conscious. Ray was already splashing around in the shadow of the bridge, huge and smiling. The artists began running single-mindedly towards the water, but before they could reach it whatever was holding their bodies together was disappearing, and they were scattering across the beach. Where they fell there were now more objects: ropes and combs and potato mashers and bicycle seats. I picked up a box and tried to collect all the pieces, but it felt futile: there was too much to pick up. When I saw that Ray was beckoning to me from the water, I jumped in.

The Part with the Telephone:

The water was so cold I thought my heart would freeze. Was I still holding the box? I suppose I was. I sunk down into the black water, clutching the box to myself for warmth, and when I opened my eyes everything was red, like a darkroom with a red lamp. In fact, that’s exactly where I was: in a darkroom, where a string of red photographs was suspended above red plastic chemical tubs. All the photographs were of mandrake roots. With their insinuations of legs or trunks or ears, some of them looked liked elephants while others looked like fetuses or rabbits. I took the photographs off the line and put them into the box. I realized a telephone was ringing somewhere. I reached over and picked up the handset. It was Ray’s voice. He wanted to know why something wasn’t in “the show.” I was confused. “Bring the beach box you’re holding!” said Ray. I said I would, even though I didn’t understand. He hung up. I was incredibly confused. There was the sharp noise of cracking celery, and I turned around.

The Part with the Auction:

The face of a horse-sized rabbit hovered in space, crunching down on a carrot and thumping the floor with its six-foot-long feet. It was the biggest rabbit I’d ever seen, and Ray sat on its back, holding on by its ears. He was inside some kind of ring, the kind you might find at a horse show. This was an indoor stadium and there were hundreds of people milling around the stands. Ray reached over the fence, took the beach box from my hands, and rode the rabbit into the middle of the ring. The audience took their seats. The lights went down and a spotlight came up on Ray. We were waiting to see what would happen next; it was so silent. Then, a man next to me raised a white paddle. Instead of Ray speaking, it was the huge rabbit doing the talking in Ray’s voice. “I have two hundred,” it shouted. “Do I hear two-fifty?” A woman in a broad-brimmed white hat raised her paddle. “Two-fifty! Three hundred?” said the rabbit. The man next to her raised his paddle, and the numbers kept going up and up. It seemed everyone had a paddle and everyone was using it. Even I had a paddle. I raised it into the air. Ray pointed at me in the audience, and a sudden spotlight blinded me. There was a hush in the stadium. “He’s bought it now, ladies and gentlemen!” Bought what? My stomach dropped. What did it cost?

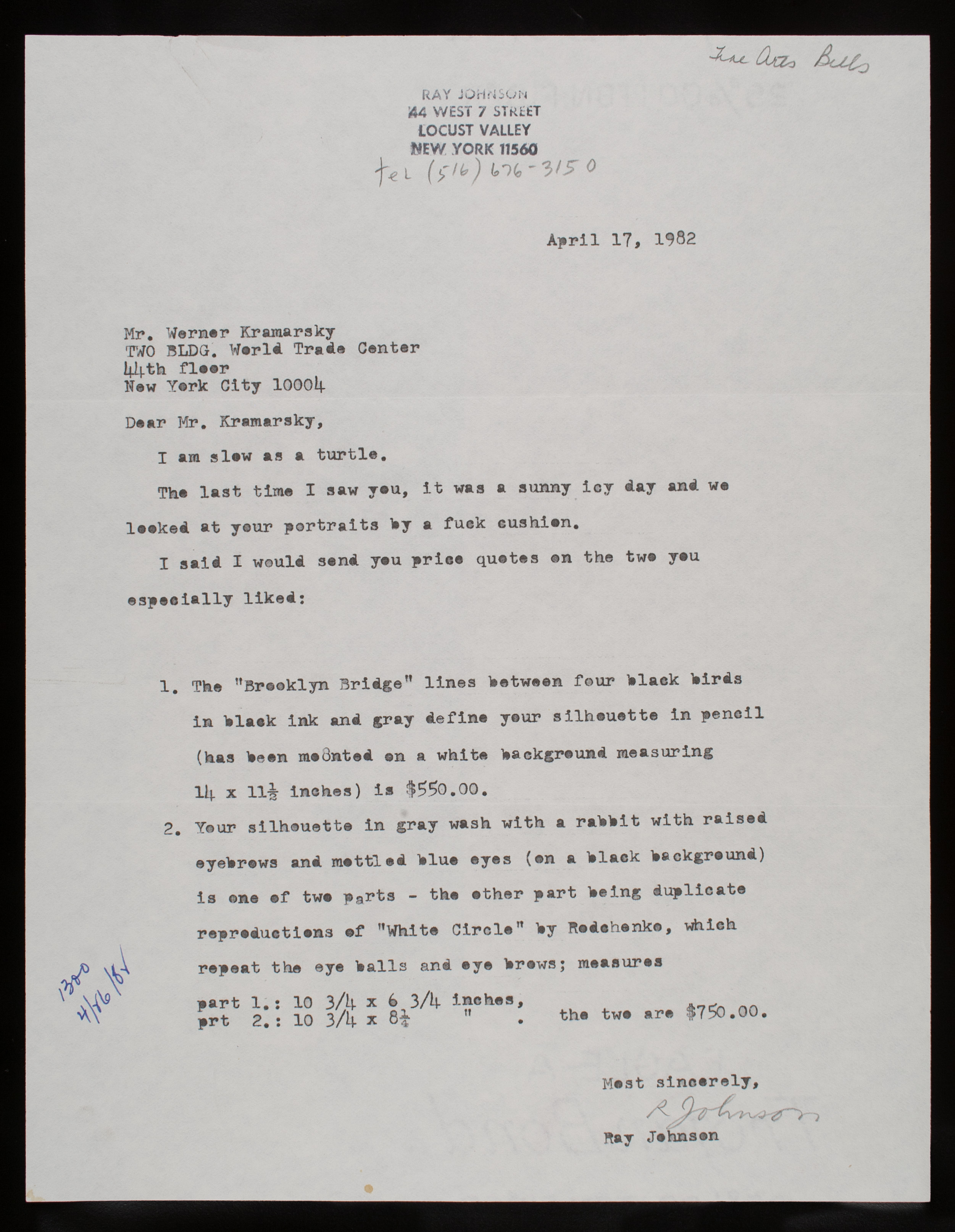

The Part with the Letter:

I ran to a place that was simultaneously all the places I’d ever lived. The living room, for example, was a mix of childhood and adulthood, and the walls were striped in two shades of green, glacial and avocado. I sat down at the kitchen table. I was forcing open an envelope with a pen. Inside there was a Xeroxed profile of a man’s head; its jaw was missing. For upper teeth, someone had written in tiny architectural caps, “PLEASE DRAW SOMETHING IN THE SPACE PROVIDED.” I looked through the window and drew what I saw: a man swimming in the water in January.

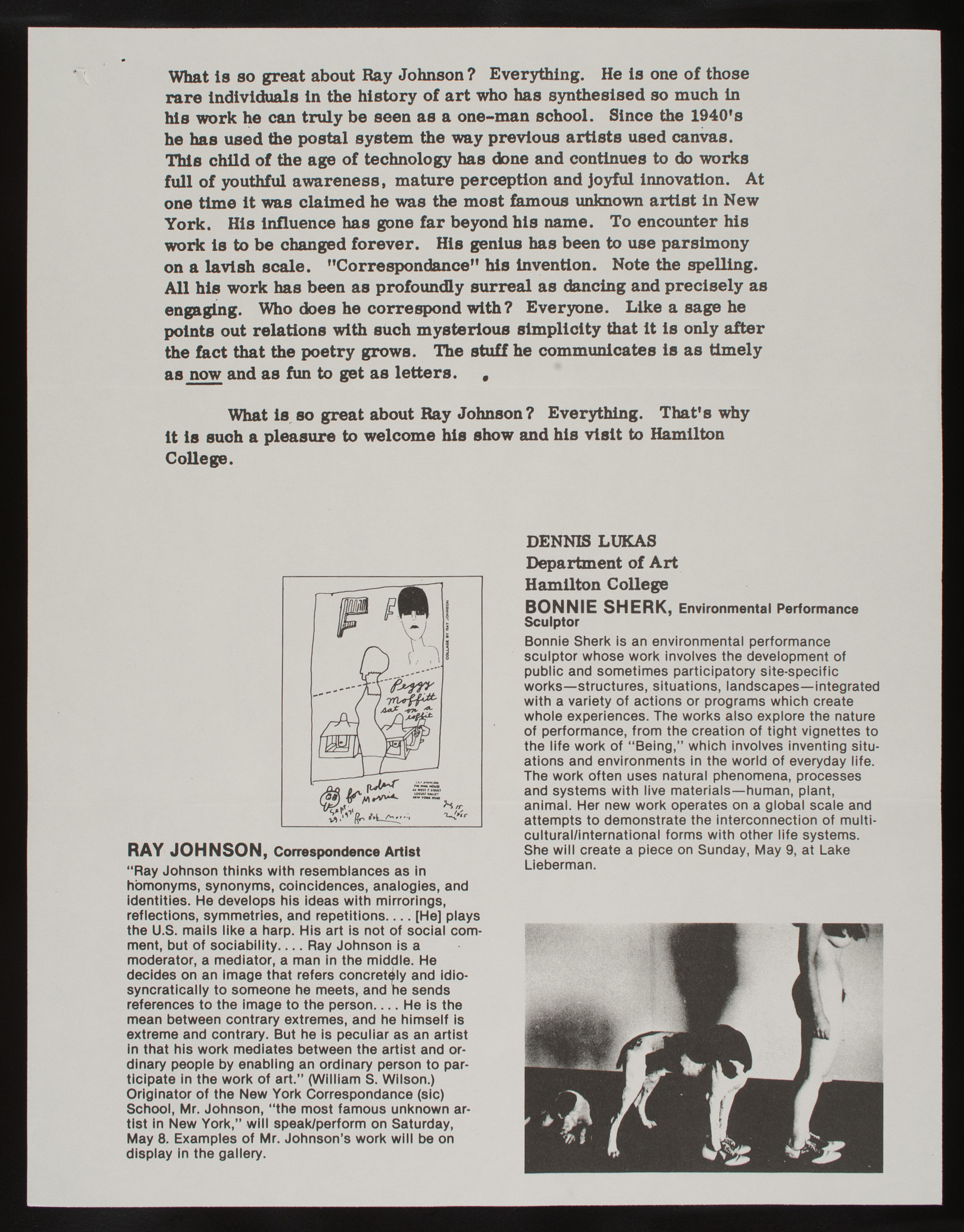

Ray Johnson Biography