Audio Transcript

When I look at the Roman alphabet, I immediately translate it. I don’t look at it as drawing; I read meaning into it. But when I look at other alphabets, Chinese or Sanskrit or Aztec hieroglyphics, or what have you, because I can’t read them or I can’t decipher them, I encounter them as drawings and as marks that could be three-dimensionalized into sculpture. A lot of the drawings that I made during this period were, in a sense, explorations into configurations that I might someday turn into sculpture. I started to look at all these different ancient languages, which did not use the Roman alphabet or the Greek alphabet, and I looked at them as drawing and as sculpture. Then I thought, wouldn’t it be interesting to take these pictographs and hieroglyphs and other visual languages and make them into a kind of a garden? It would be a topiary, like the grand English and French gardens. So the fantasy was to make this grand garden in which, as you moved through it, you would see these weird topiaries—but if you knew the secret language, you would realize that you were moving through the history of language and the history of human thought. I think language, and particularly written language, may be one of our greatest assets as human beings.

I used all kinds of things: I used parts of the Rosetta Stone, which has always been my favorite. I used a hobo language, I used Sanskrit and Arabic; I found a script that supposedly was the angels’ writings. I’m sure that was made up by some Early Christian who thought he or she had access to how the angels would write, so I put that in. And then I found the devil’s handwriting, and I put that in. And everything that I thought would really make good calligraphy, good drawing, good sculpture, I put in there, that was also mysterious to me in terms of the fact that I could not translate it, I could not decipher it, so it just looked like art. And I used a French garden—which may have been Villandry, I’m not absolutely sure—as my template. And in my megalomaniac fantasies, someday I would like to see the garden made. But it’s not likely, so the drawing exists.

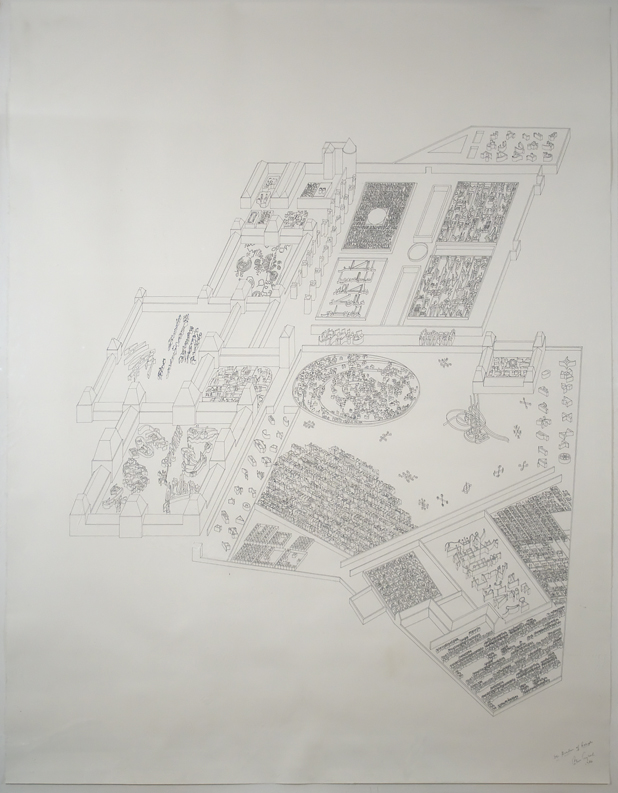

At first glance, Alice Aycock’s The Garden of Scripts (Villandry) from 1986 resembles a drawing by a landscape architect for a potential client. Upon closer examination, one realizes that this garden is filled with characters from various languages. The three-dimensionality of the scripts exposes this drawing as the work of a sculptor. In fact, Aycock drew The Garden of Scripts as a topiary-filled labyrinth, intending fictitious visitors to “walk in and throughall [of] these languages,” which is aligned with the artist’s wish to eventually translate this garden into sculptural form.1

Familiarity with Aycock’s background and work as a sculptor provides additional insight into this particular work on paper. For instance, the spiraling details resemble some of her more iconic structural forms, while the freestanding letters display her consistent curiosity and whimsicality. The artist’s deep interests in history, other cultures, fantasy, and time travel are revealed in her choice of a grand French garden composition—although Aycock later realized that the garden depicted here is not, in reality, the garden at Villandry, as the title suggests. Some of the artist’s earlier works were land pieces that involved reshaping the earth; this history is evident in her delicate portrayal of these linguistic sculptures as seemingly organic forms.

Within this metaphorical garden are a multitude of ancient written languages, including Aztec, Chinese, Sanskrit, Arabic, Hebrew, hobo code, hieroglyphics, and cuneiform. It was important to Aycock that all of the text be significant in some way, which influenced her choice to include parts of the carvings from the Rosetta Stone. Through the architectural translation of language, the artist poses a unique conceptual and visual contradiction by placing scripts within a landscape—encoding one thing within another.

As she mentions in a recording about this work, here Aycock echoes her initial rumination on animal tracks. For the artist, such markings left in the snow or dirt become “magical…signs of power” given their ability to serve as a means of communication between various living creatures. Moreover, tracks that can stand alone—without translation—take on new meaning as symbols and insignias of sorts.2 Aycock once said, “Meaning is always arbitrary, but the sign [i.e. the work of art] stays there and floats until some other arbitrary meaning flows into it.” In this way, Aycock portrays language (like art) as a visual experience, rather than as an arbitrator of objective meaning.3

Alongside her interest in indecipherable languages, Aycock was drawn concurrently to the concept of private gardens and “little worlds” like that of Charles Dickens’s Madame Defarge (Tale of Two Cities) or Hadrian’s Villa. Aycock arranged her personal garden using diagrams of ancient battles, although the plantings have since become overgrown and now lack any evidence of their original order. Similar to the secret code of her own garden, Aycock intended for this fantasy drawing of topiaries in the form of calligraphic figures and pictographs to remain a mystery. The Garden of Scripts is ultimately a place where visitors may stroll through the history of language and human thought—yet remain completely unaware of the meaning embedded within the surrounding vegetation.

1. Jonathan Fineberg, Complex Visions: Sculpture and Drawings by Alice Aycock (Mountainville, NY: Storm King Art Center, 1990), 27.

2. Alice Aycock, audio commentary, 22 June 2011.

3. Robert Hobbs, Alice Aycock: Sculpture and Projects (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 154.

Alice Aycock Biography