“People sometimes say about my painting, ‘That’s a real Happening.’” — Jim Dine1

In the early 1960s, Jim Dine was one of the leading artists of a new inter-media performance art. Combining performance, visual art, spoken word, and music, these Happenings trace their origins to an event staged in 1952 by John Cage at Black Mountain College. Cage read excerpts from Zen texts, selections from Meister Eckhart, and played a radio; Robert Rauschenberg displayed his White Paintings, upon which shadows fell and random images were projected; dancer Merce Cunningham led dancers through the audience aisles; musician David Tudor played a prepared piano and poured water between two buckets; while poets Charles Olson and M. C. Richards read poetry. Although Cage organized the event, the performers were free to structure the time that they were given.

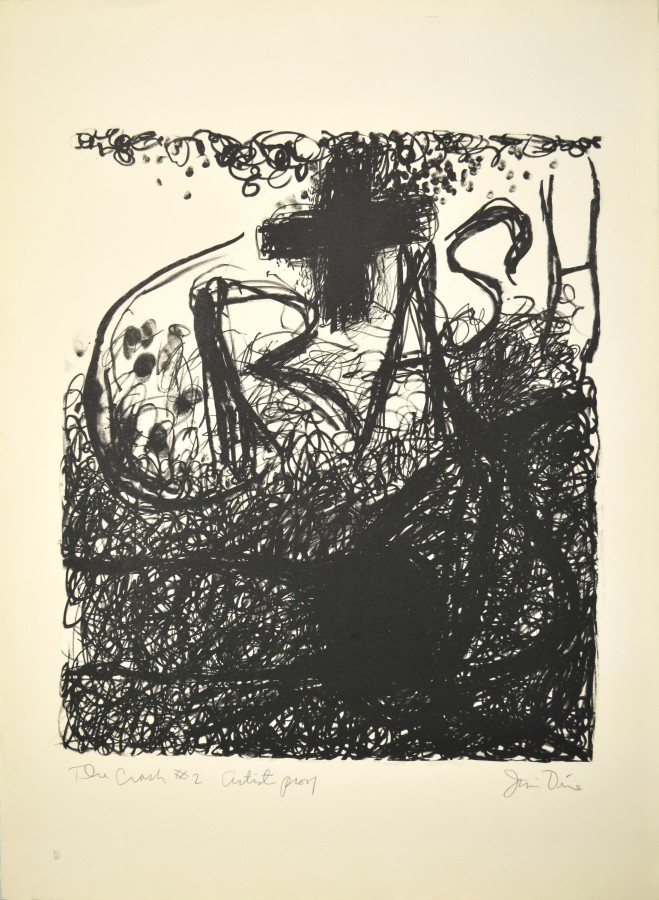

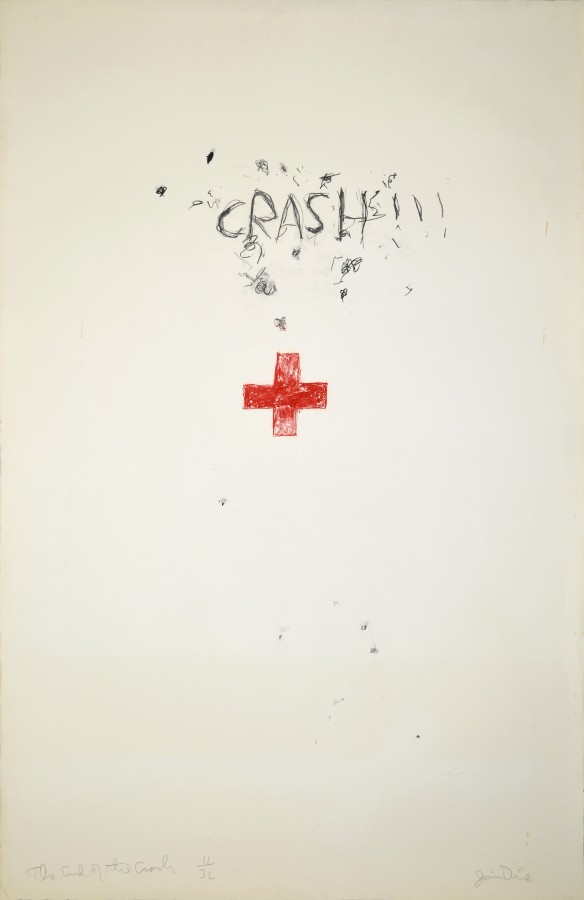

When Cage began teaching at the New School for Social Research in 1956, among his students was Allan Kaprow, who would later meet Dine in 1959. Together they pioneered the Happenings movement. The Crash #2 and The End of the Crash belong to a series of lithographs Dine created to accompany his 1960 Car Crash happening, which recalled two crashes Dine had suffered: the first, in which Dine was thrown from the car, was precipitated by the shock of hearing news on the radio of the death of a friend in an accident; and the second, in which his wife, Nancy, broke her arm while securing their son, who was riding in the backseat. The Car Crash performance was an emotional exorcism in which Dine, assisted by three others, attempted to recount the events’ terror to the audience.

From November 1 to 6, 1960, Dine performed the fifteen- to twenty-minute Car Crash six times at New York’s Reuben Gallery. The anteroom of the gallery was filled with paintings, drawings, and lithographs—including these two—displaying a shared imagery of tire-like circles and crosses. The gallery room was filled with various tubes, belts, cords, and other debris, all of which was whitewashed. From the ceiling hung a silver foil-covered cross; additional crosses hung or were painted on various surfaces. In the dark, accompanied by recordings of honking and other traffic noises, Dine entered the room wearing a silver jumpsuit, a bandage wrapped around his head, white face paint with black eyeliner and lipstick accentuating his features, and two lights attached to his head. While emitting a stream of guttural sounds and despairing moans, Dine frantically drew, erased, and redrew a car on a blackboard. Dine represented the car itself, while two flashlight-bearing collaborators represented other cars, repeatedly re-enacting the accidents by “crashing” their beams into him. A third collaborator recited a Dada-esque stream-of-consciousness recounting of the crash, which sounded extemporaneous but had actually been carefully scripted by Dine.

Akin to the operation of concrete poetry, here words and images combine to evoke a comprehensive account of the crash. The word crash functions as both a noun and a verb: the energetic scribbling conveys the action of the crash, while the cross designates the site of the crash itself. The tangled black lines and spider-like arrangement import an ominous quality to the work, which underscores the inherent violence of the event. In contrast to The Crash #2, in which the word is enmeshed within a web of black lines, in The End of the Crash the word crash materializes seemingly out of nowhere, emphasizing the frightening suddenness of the event. The presence of the cross (an iconic red in The End of the Crash) helps shape our interpretation of the word crash, as it implies the presence of victims. The Crash series is, as Jean Feinberg noted, “a potent metaphor for danger, tragedy, and the omnipresent specter of death that Dine sensed in American life.”2

The chaotic scribbling represents the snarl of Dine’s emotions and echoes the Abstract Expressionists’ gestural brushstroke, that indexical trace of the maker’s body. Dine materializes this boundary between body and memory, between what we can see and what we cannot. In tracing the lines with our eyes, we recreate the action of Dine’s hand as he created them. The black lines additionally call to mind the dizzying trajectory of the crash. Whereas Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns ironized the gestural brushstroke, revealing the fraudulence of its promised authenticity, Dine embraces it, putting it in service to the work’s deeply personal and emotional import.

The Crash series helps illustrate the complex interplay between word and image that was under investigation at this time. While the totality of the work evokes the idea of a crash, Dine’s use of nonsensical language underscores the impossibility of accurately communicating the individual truth of such an experience. At its heart the work challenges the notion of a totalizing meaning fixed by the maker, requiring viewers to draw upon their own unique experiences to complete the work.

1. Michael Kirby, Happenings: An Illustrated Anthology (New York: Dutton, 1966), 203.

2. Jean E. Feinberg and Jim Dine, Jim Dine (New York: Abbeville Press, 1995), 16.

Jim Dine Biography

Sarah JM Kolberg Biography