The consensus culture of Cold War America demanded conformity to a narrow constellation of prescribed behaviors and beliefs. Fear of Communist infiltrators was widespread, making all forms of difference threatening. Homosexuals were singled out as particularly vulnerable to Communist blackmail and thus were considered inherently untrustworthy. The prevailing understanding of homosexuality at this time did not include notions of love, only of deviance. Words such as love, so innocent in a heterosexual framework, became tainted with political threat when employed in a homosexual context. It is little surprise that gay artists were at the vanguard of an art-making practice that was simultaneously resistant to dominant culture’s impositions of power and illegible as such.

In the midst of these social conditions, Abstract Expressionism was the prevailing artistic movement. It entailed the conflation of artist and viewer, in the form of an expression of the artist’s inner self that would be immediately and emotionally understood by the viewer. Planning was to be avoided, and spontaneity, accident, and improvisation were privileged as the unmediated expression of the artist’s psyche. The presumed direct correlation between artist and mark made the gestural brush stroke the hallmark of Abstract Expressionism: gesture and identity became discursively synonymous.

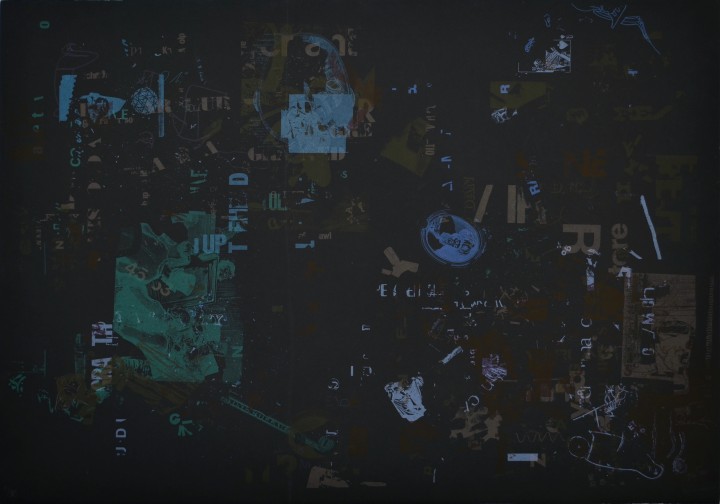

The critical reception of Abstract Expressionism made evident that not all artists can express equally. Personal expression for homosexual artists was dangerous, if not impossible, and challenging the presumption of a recoverable authorial presence became a centerpiece of their formal strategies. In refusing the formal qualities of Abstract Expressionism, gay artists sought to reject and reframe its ideological paradigms as well. In his 1952 work Untitled (Mirror), Robert Rauschenberg utilized a variety of techniques to create the image: oil and watercolor paints, pencil, collaged paper, crayon, and transfer drawings. A wide swath of white paint sweeps across the top of the canvas, below which a transfer drawing from an Old Master work has been framed in colored pencil. A collaged swatch of paper is the base for a variety of media: another solvent transfer, paint, crayon, and colored pencil. In presenting this diverse catalog of mark-making, Rauschenberg opens his canvas to multiple readings and refuses a singular organizing presence. He calls into question the privileging of one form of mark-making over another, challenging the Abstract Expressionist doctrine that valued the gestural mark above all else. That Rauschenberg’s image catalog was primarily drawn from other sources underscores the degree to which expression is always written in forms that originate outside of the self.

Among the solvent transfer images is one of a baby in a playpen. The baby may well be Rauschenberg’s son with Susan Weil, Christopher, who was born the year prior to this work, and who appears in other works such as Canyon (1959). Weil and Rauschenberg met at Black Mountain College, where he also met Cy Twombly; less than a year after he married Weil, Rauschenberg found himself falling in love with Twombly and left Weil and their infant son for a relationship with Twombly. By the time of Untitled (Mirror)’s creation, Rauschenberg and Weil were already separated. It was not an easy break, as Rauschenberg was torn by the conflict between the responsibility of marriage and family and following his heart. Thus even this image of a baby is made to mean multiply, standing as a symbol both of marriage and the heterosexual family unit, and of the dilemma the artist faced in wishing to live a life more true to himself, a life that meant being romantically involved with men.

Rauschenberg includes other images that similarly point to this dilemma, such as the solvent transfer of an Old Master Venus, which is a frequently recurring motif in Rauschenberg’s work. As Kenneth Bendiner notes, Rauschenberg reproduces a Cranach Venus in Levee (1955), a Titian in Odalisk (1955-58), a Velázquez in Barge (1962), a Michelangelo in Estate (1963), and a Rubens in Persimmon (1964), as well as others in Rebus (1955), Short Circuit (1955), Bicycle (1963), and Tracer (1964).1 Bendiner posits that the Venus transfers function “primarily as signs of love,”2 giving them an ironic twist considering Rauschenberg’s romantic interests.

The work’s title is drawn from a headline fragment from England’s daily tabloid, the Daily Mirror, and acts as a signpost to one of the work’s most significant thematics. Mirrors recur frequently in Rauschenberg’s work, adding layers of signification, whether within a transferred image, such as the fragment of Rubens’s Venus with a Mirror in Persimmon (1964); as an actual 3D object affixed to the surface, such as in Charlene (1954); or hanging from the work as in Minutiae (1954). At its most basic, the mirror is a trope of psychological self-awareness, from simple notions of self-reflection to Lacan’s Mirror stage, in which the child develops an awareness of its own subjectivity. For Rauschenberg, mirrors emphasize the individuated encounter rather than a universal or collective experience. In the works that include a physical mirror, the viewer’s reflection is incorporated into the surface of the works, materializing Rauschenberg’s emphasis on the centrality of the viewer. Moreover, since what is reflected changes with every viewing environment, Rauschenberg further destabilizes the idea of a work’s fixed and unchanging meaning, instead opening it up to an endless stream of potential significances. Finally, the mirror ironizes one of the prevailing ways in which homosexuality was then understood. Based on the Greek myth of Narcissus, who fell in love with his own image, Freud proposed that homosexuality was the result of a faulty object-choice in that the homosexual is attracted to someone whose gender matches his own: his mirror image.

As do many titles, the word Mirror serves as an organizing rubric guiding our contemplation of the work. As a word, Mirror is more noticeably reversed than some of the other pictorial elements, which spurs the viewer to consider the import of its reversal. Its adjacency calls our attention to the Statue of Liberty’s reversal, so subtle that one might not notice the flipped position of her arm holding the torch. Untitled (Mirror) is one of Rauschenberg’s earliest works using the solvent transfer method, which would soon become the bedrock of his artistic practice. This method involves the transfer of an image from a printed source – most frequently newspaper and magazines – which is soaked with xylene or other chemical solvents, laid onto a new surface, and rubbed with a burnishing tool, transferring the ink from the source to the receiver. The source image is reversed on the receiver, a consequence which is usually incidental and without any symbolic import. However, the reversal here of the Statue of Liberty—our nation’s symbol of hope, opportunity, and freedom—carries implications of the myriad ways in which those privileges are often denied gay and lesbian individuals.

1. Kenneth Bendiner, “Robert Rauschenberg’s ‘Canyon’,” Arts 56 (1982): 57-59.

2. Ibid, 57.

Robert Rauschenberg Biography

Sarah JM Kolberg Biography