Building on Nathan Langston’s fascinating discussion of ekphrasis, the act of translation of ideas from the visual to the textual, I’d like to re-focus on his mention of “information.” As Nathan put it, “the very premise of the show concerns the relationship (or sometimes disconnect) between information communicated as text and information communicated visually. There are both differences and similarities between the ways these two forms convey information…”. I’d like to delve a little bit deeper into this idea of “information communicated visually.”

It’s a cliché by now to point out that we currently live our lives surrounded by “information,” right? We have Wikipedia at our fingertips and newsflashes beamed across our buildings. We have so much information available to us that we have to organize it into charts, graphs, and color-coded maps. This sea of visual information is only going to get deeper as we get closer to the November elections. We’ve all had to become experts at recognizing these charts and digesting them.

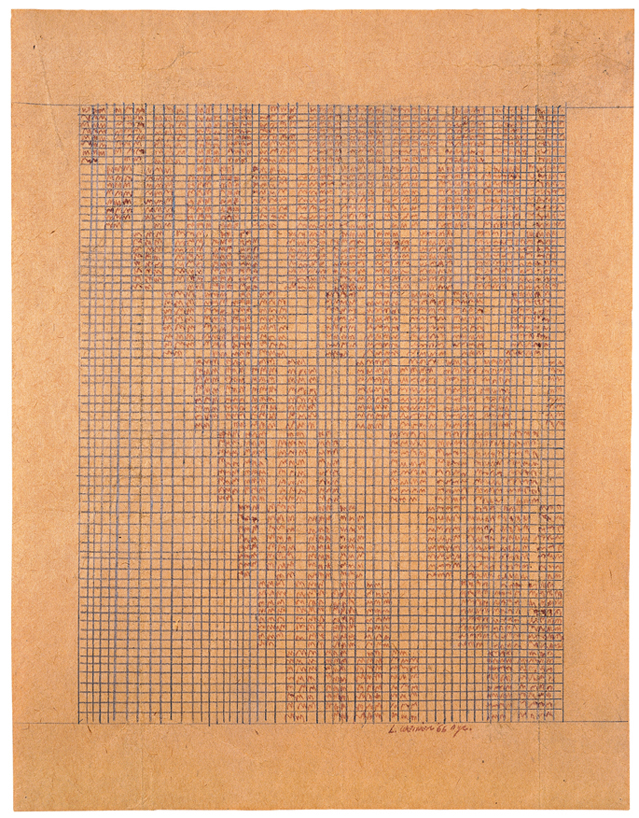

I’m interested in how these skills at extracting data from the visual translate when we turn our gaze to the art object. I’m especially interested in artists whose works use the trappings of the chart or the graph to encourage us to try to decode their work, only to frustrate us by not providing clear answers and data as such. My impression is that it’s this frustration of expectation that makes these works so powerful, though I’m still trying to puzzle out exactly how this works.

What do you think — is there an overlap in how we read a newspaper graph and how we read a work of art? Is there a difference between how we approach a drawing like Mark Lombardi’s or Lawrence Weiner’s and how we might approach another drawing? Do you try to read information into Stefana McClure’s and Stephen Dean’s work? Is that “reading” a part of the viewer’s experience of the work? How do these works, even at their most informational, manage to expand beyond the informational?

Emily Sessions (b. 1980, Philadelphia, PA) is a PhD student in the History of Art at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. She received her BA in Psychology and Anthropology from Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts, and her MA in Art History from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. She has worked at such institutions as the Brooklyn Museum, New York; the Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University; and the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, New York. Sessions has published and presented on subjects ranging from medieval mappaemundi to relational aesthetics. She lives and works in New York City.