Verb List is far more than it seems at first glance.

Verb List holds the kernels not only of the artistic revolution brewing in American art during the 1960s, but of the monumental body of work that Richard Serra has been creating ever since. Serra made Verb List shortly after he moved to New York in 1966, following two years of travel and study in Europe. Living in New York’s then rough-and-ready SoHo district, he was part of a circle of artists, musicians, dancers, and filmmakers who were breaking down the boundaries between painting, sculpture, drawing, performance, and film to create works of art that directly reflect the artist’s actions and engage the viewer.

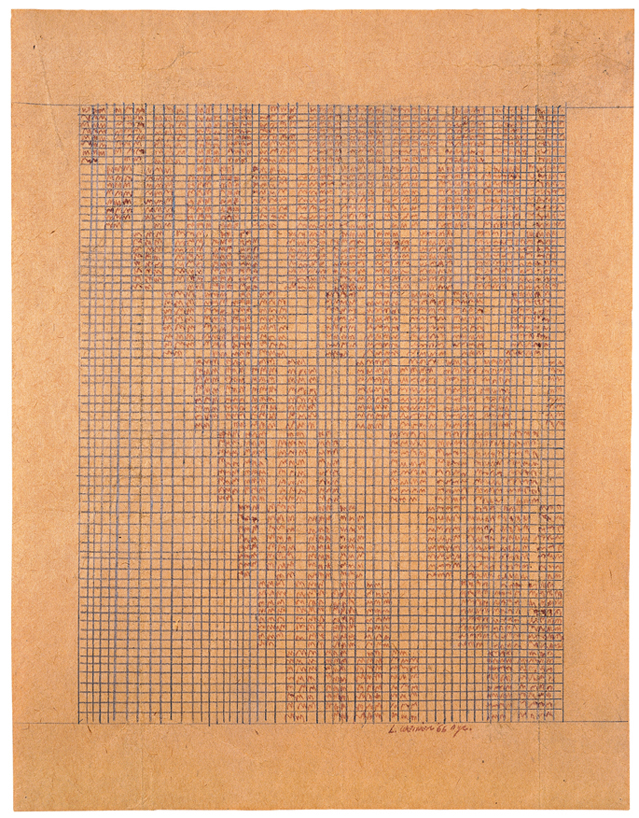

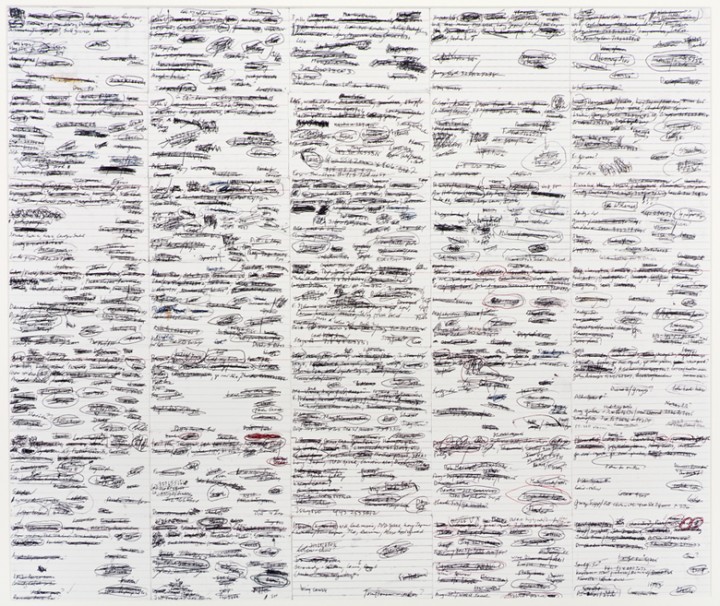

Serra was in his late twenties when he created Verb List in 1967–68. At the time, he did not consider it a work of art but thought of it as a way of figuring out his own direction as a young artist. In a recent interview, Serra said: “The Verb List gave me a subtext for my experiments with materials. The problem I was trying to resolve in my early work was: How do you apply an activity or a process to a material and arrive at a form that refers back to its own making? That reference was mostly established by line. In a sense you can’t form anything without drawing.”1

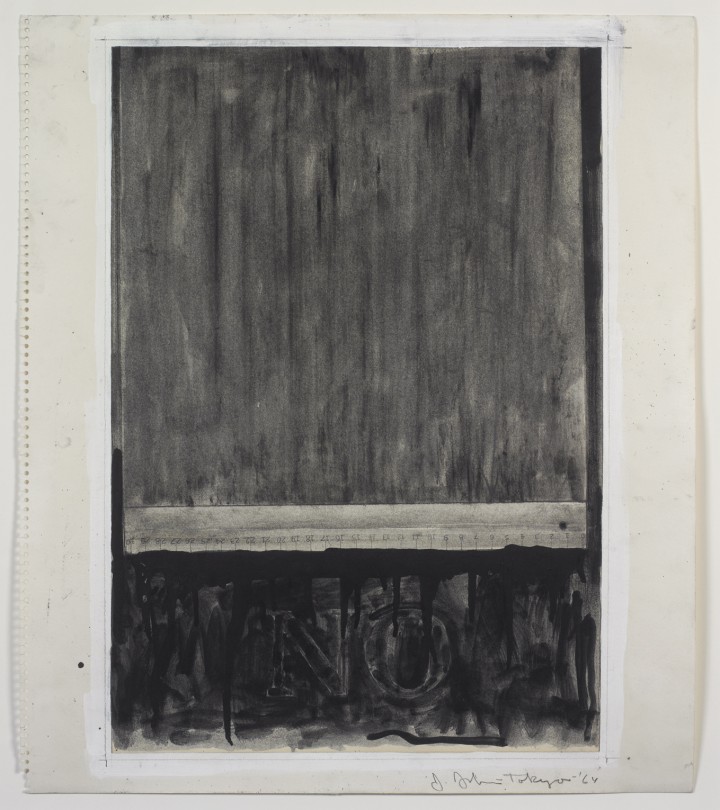

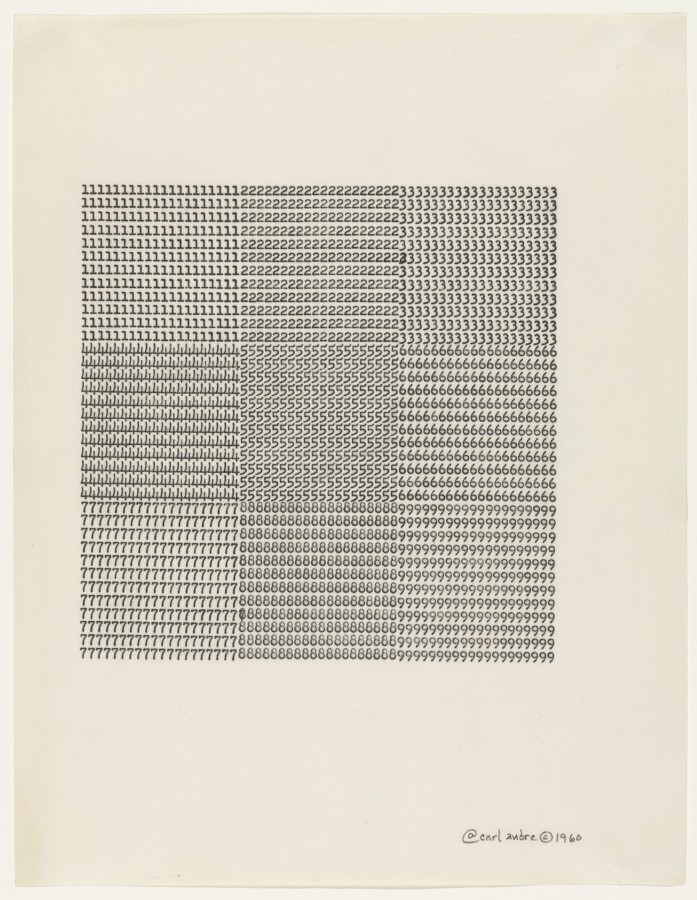

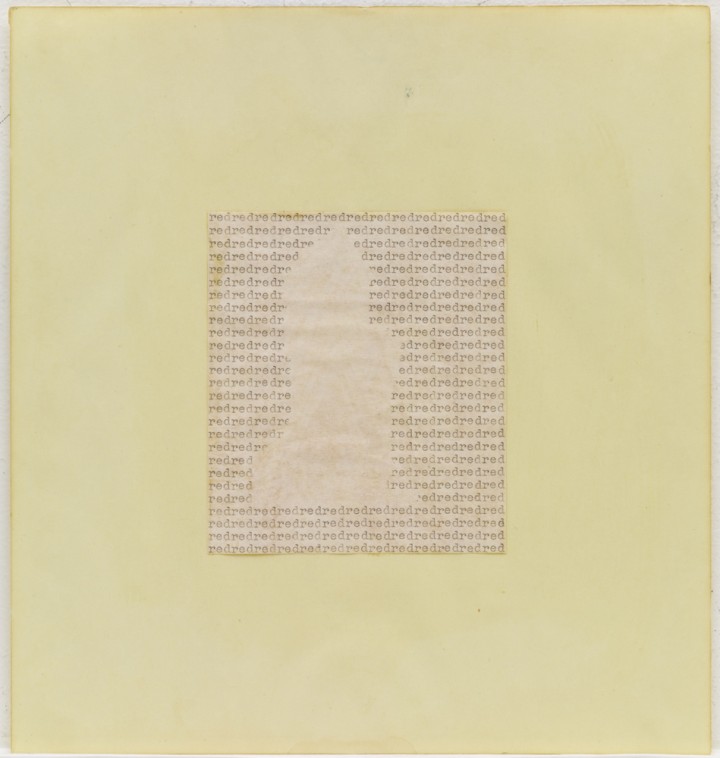

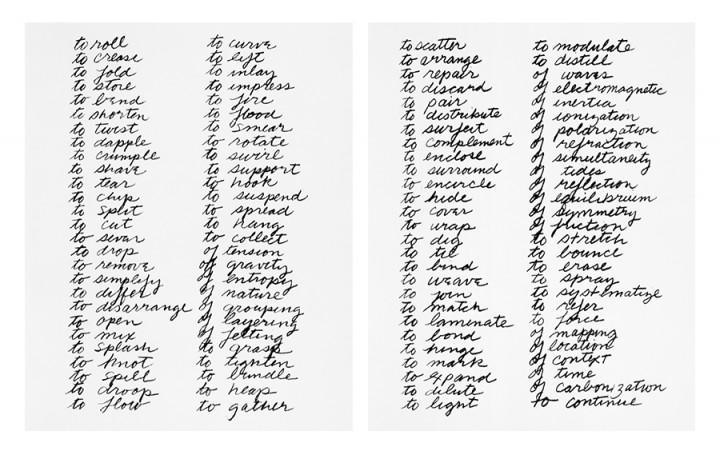

For Verb List, Serra wrote out in an assertive hand, well trained in the Palmer Method of penmanship, four evenly spaced lists of words on two ordinary eight-by-ten-inch sheets of paper. The words he selected were muscular and task oriented, and they show his kinship with the choreographer Yvonne Rainer, whom he considers an important influence on his early development as a visual artist. In fact, Serra’s choice of words—to roll, to fold, to bend—echoes Rainer’s 1965 manifesto in which she bravely states: “No to spectacle no to virtuosity no to transformations and magic…,” in her search for a new dance based on ordinary tasks rather than dramatic movement.2 Read out loud, the repetitive cadence of Verb List recalls the innovative music of the composer Philip Glass, a longstanding friend and, at the time, Serra’s neighbor and sometime collaborator in the moving business he started to make ends meet.

Regardless of the media, Serra and other vanguard artists of the 1960s were dedicated to the process of making art rather than to the creation of expressive objects or performances. Actually called Process art, this new approach changed the course of art in the past 50 years and gained early public exposure in three landmark exhibitions held in 1968–69: Square Pegs in Round Holes, or Op Losse Schroeven at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam; Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York; and Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form: Works – Concepts – Processes – Situations – Information, which opened at the Kunsthalle Bern, Switzerland, and traveled to two other venues in Europe. Featuring the work of 69 American and European artists, When Attitudes Become Form focused on works that showed the artist’s activity—forever transforming the relation of the artist, the audience, and the museum. Serra showed three sculptures, including a piece he made on site in the museum by splashing lead against a wall.3

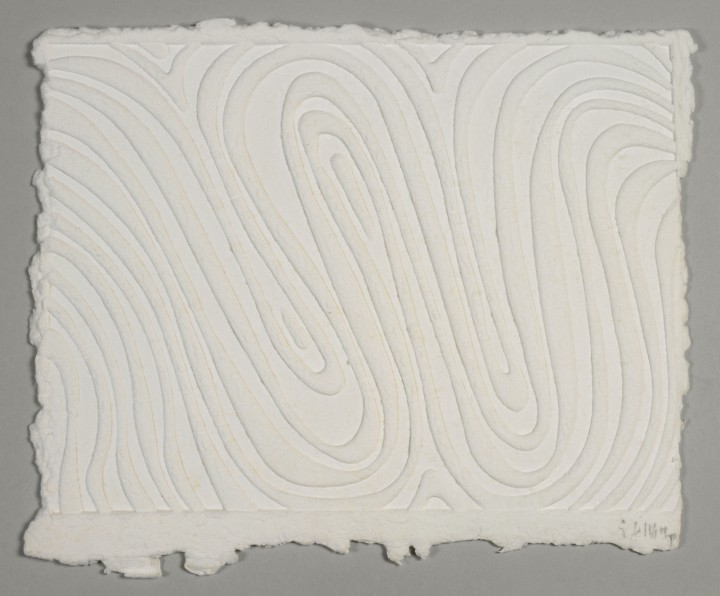

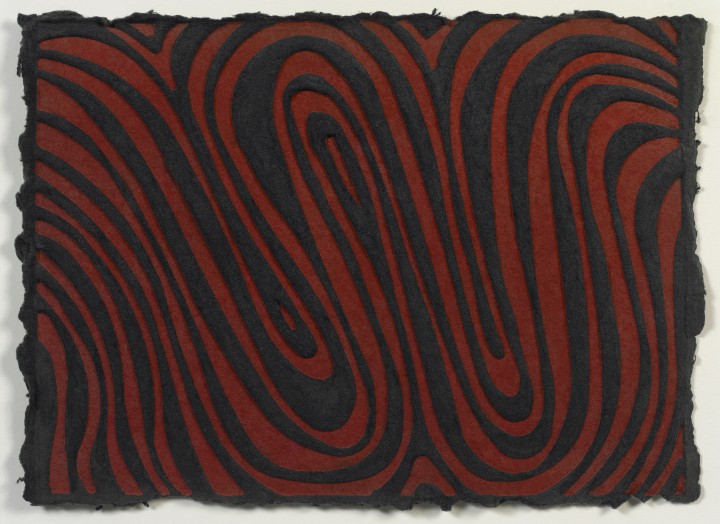

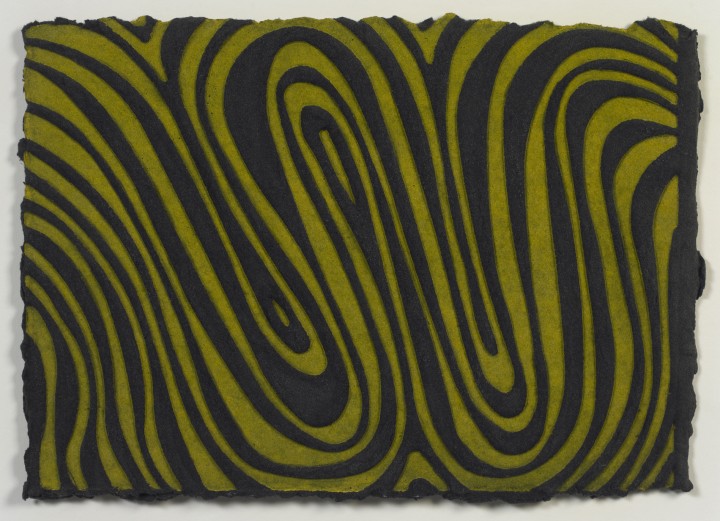

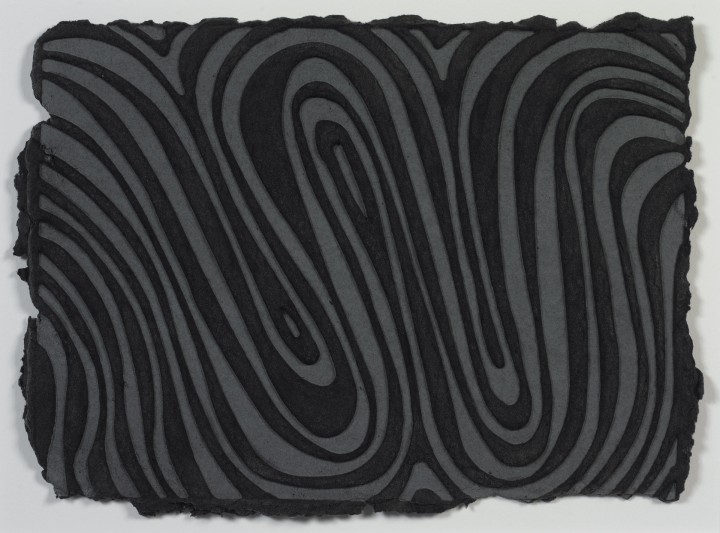

Since those heady days in the sixties and the birthing of Process art, Serra has created a powerful body of large-scale installation drawings with oil stick and monumental steel sculptures that continue to embody the possibilities that he mapped out in Verb List, impacting the way a viewer experiences the passage of time and the physical act of moving through space. As he continues to create masterful sculptures around the world, Serra also keeps sketching, as he did as a boy growing up in California: “Drawing for me is a way to keep my hand and eye conditioned and to keep my mind nimble.”4

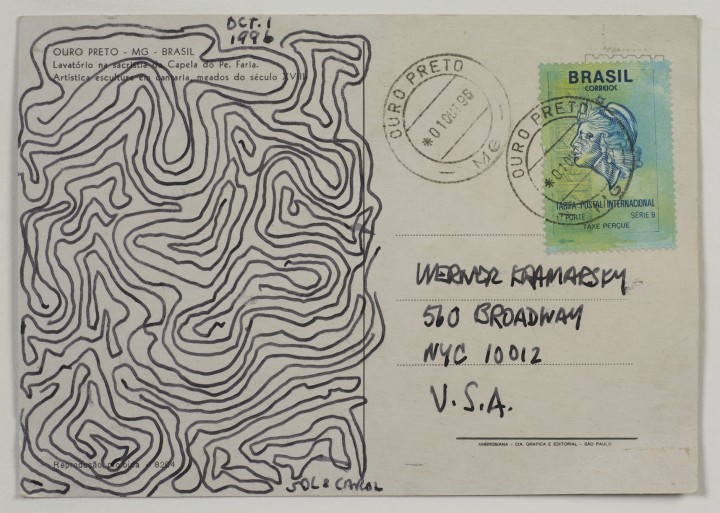

Today, nearly fifty years after Serra made Verb List, this seemingly unassuming work is considered an iconic art object. Verb List was the earliest work included in the major retrospective of Serra’s drawings shown in New York, San Francisco, and Houston in 2011–12. Serra kept Verb List in his personal collection until 2012, when he gave it to New York’s Museum of Modern Art in honor of Wynn Kramarsky—a tribute to their enduring friendship and mutual respect for machine shops, “shop talk,“ and the well-made object.5

1. Richard Serra quoted by Gary Garrels in “An Interview with Richard Serra (2010)” in Richard Serra Drawing: A Retrospective (Houston: The Menil Collection, 2011), 61.

2. Yvonne Rainer, Feelings Are Facts: A Life (Cambridge, Massachusettes: MIT Press, 2006), 263.

3. See Christian Rattemeyer et al., Exhibiting the New Art: ‘Op Losse Schroeven’ and ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ 1969 (London: Afterall Books, 2010).

4. Serra quoted in Garrels, 81.

5. Wynn Kramarsky in conversation with the author in July 2012.

Richard Serra Biography