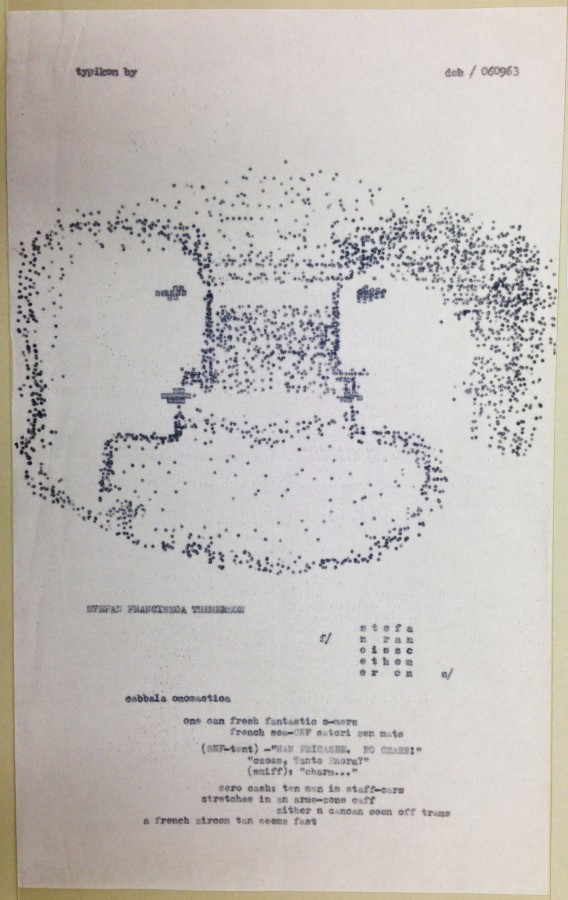

Some of the 1960s’ most important visual poetry came from an exceptionally unlikely source: a Benedictine monk from England’s Prinknash Abbey. Dom Sylvester Houédard, or dsh, as he signed his works, was one of the period’s most prominent concrete and visual poets. Houédard published extensively in small press literary journals, including Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Poor. Old. Tired. Horse., and maintained a correspondence with many of the leading poets and language innovators of his day, even collaborating with some of them, including John Cage, Gustav Metzger, and Yoko Ono. Educated at Oxford before ordination, Houédard evinces a profound intellectual engagement in his critical writings, citing Postmodern theorist Rosalind Krauss and philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein with as much facility as biblical verse.

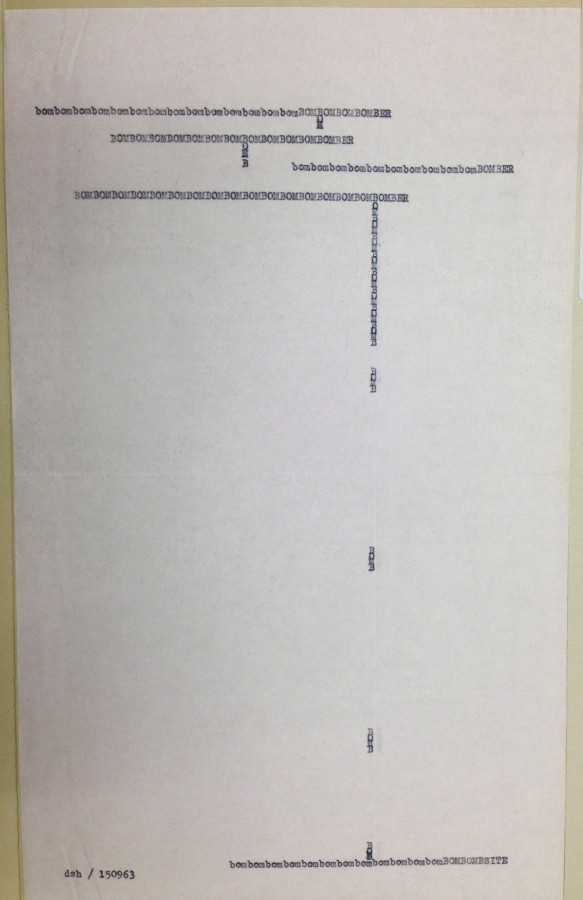

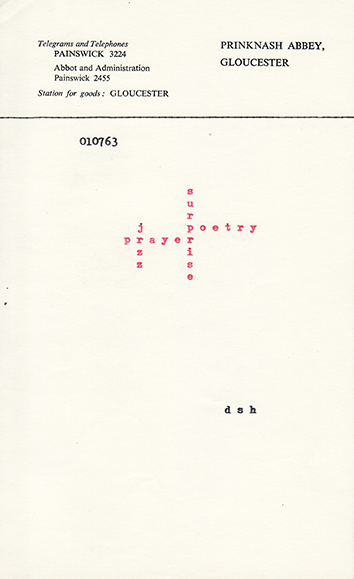

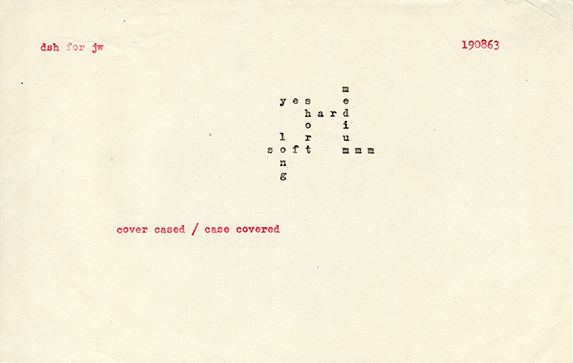

Almost all of Houédard’s works were composed on his portable Olivetti Lettera 22 typewriter, many on Abbey letterhead, and often using the different colored ribbons available for this model, an aspect of his work that was frequently lost in publication. Houédard’s use of the typewriter gave rise to the neologism “typestracts” to describe his poems, and he is recognized as one of the leading practitioners of typewriter art. Like Finlay, he alternated between concrete poetry, such as bombombomb… and typikon by, and visual poetry, such as cover cased / case covered and prayer poetry, all from 1963.

bombombomb… illustrates concrete poetry’s precept that the image created by the poem’s words serves as a visual analogue to the idea expressed by the poem. As such, the arrangement of the words takes precedence over syntactical concerns, and traditional poetic values such as rhythm, meter, and metaphor give way to spatial arrangement, negative space, and visual architecture. bombombomb… consists of the arrangement of ten letters and three words: bomb, bomber, and bombsite. Arranged horizontally across the top of the page, four rows of varying length spell out bombombombomber, each word running into the next, evoking the anxiety of a sky filled with planes arranged in the finger-four tactical formation of the Luftwaffe. A steady stream of BOMBs drops vertically from three of the bombers to the bombsite on the ground.

While a work like bombombomb… relies on the direct relation of word to image, many of Houédard’s visual poems relied on what he referred to as the work’s “pluritotality” – the sum of its multivalent meanings, both denotative and connotative, sincere and ironic. Houédard was a great admirer of the Beats, read extensively in and corresponded with Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, and Allen Ginsburg, and his writing reflects the jazz-inflected syntax and frank, often homoerotic, sexuality of the Beat aesthetic. Houédard’s prayer poetry links a variety of experiences—poetry, jazz, and sex—to the sublime quality of prayer.

This poem emphasizes the degree to which Houédard, and others of the time, were invested not in determining meaning for the reader, but in making readers aware of their freedom to discover new meanings. As he wrote in the catalog for the 1965 exhibition Between Poetry and Painting at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, in which his work was featured: “dictionary(convention) as language coffin – this word/poem means the WAY we use it – we (not them) convene its meaning”.1 As an example, consider the word pair prayer/jrzz which pivots off of the shared r. We must assume that Houédard intended the dual reading of jazz/jizz, considering that he could easily have shifted the vertical word one letter to the right, creating the word jazz and avoiding the suggestion of any sexual meaning. But that would have hewed too closely to fixing the word in the “language coffin” that he wished to avoid.

Are we to assume that the poem refers to the pleasures of mutual or solitary sexual satisfaction? It could easily be either, but the decidedly masculine sexual slang facilitates a homoerotic interpretation of the poem as a whole. Similarly, cover cased / case covered undertakes an investigation that, while not overtly sexual, is nevertheless all sexual innuendo and longing. The inventory of sizes (long, medium, short) and tumescence (soft, medium, hard) bracketed at the top and bottom by yes and mmm mark this work as a catalog of male homoerotic desire.

That we can read the words in cover cased / case covered in a sexual manner, against their common meanings as simple adjectives describing the physical qualities of objects, demonstrates Houédard’s investment in opening language to a “pluritotality” of meaning, even, and perhaps especially, if some of these meanings run counter to those privileged by dominant culture. Just as the alternate readings of jazz/jizz pivot on the r, the words in cover cased / case covered pivot on the totality of each individual word in relation to the whole. By enabling each word to convey both a traditional and a dissident meaning, Houédard shows that it is possible to escape the language coffin. Like his collaborator Cage, Houédard facilitates our understanding of language as an instrument of control wielded by dominant culture and the discovery of a radical freedom precipitated on our redeployment of language against it. His minimalist typestracts exemplify his desire to create “jewel-like semantic areas where poet and reader meet in maximum communication with minimum words”2: areas in which we can discover the power to create meaning, and with it, the power to create new realities.

1. Dom Sylvester Houédard, “Statement by Dom Sylvester Houédard” in Between Poetry and Painting (London: Institute of Contemporary Arts and W. Kempner, 1965), 55.

2. D.S.H., Charles Verey, and Ceolfrith Gallery, Dom Sylvester Houédard (Sunderland, Durham: Ceolfrith Arts Centre, 1972), 47.

Dom Pierre Sylvester Houédard Biography