The language divorced of any meaning becomes an object, both threatening and useless…

— Annabel Daou1

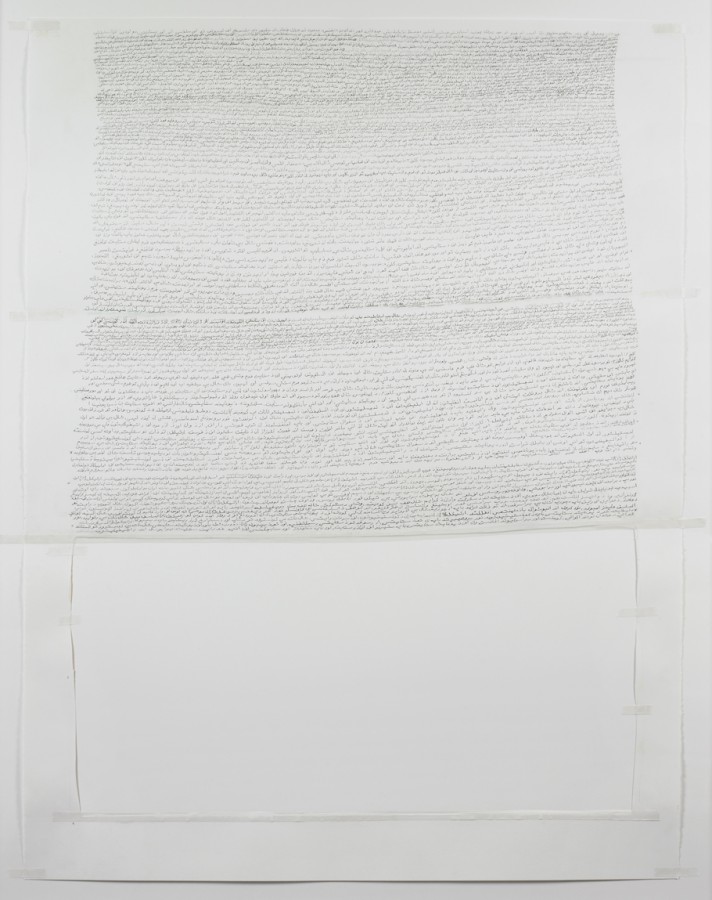

In Constitution (2004), Annabel Daou transcribes the text of the Constitution of the United States phonetically into Arabic characters. The result is not a translation of the Founding Fathers’ document, nor even a careful and systematic transliteration of the English words using the Arabic alphabet. Daou made this work as she read the Constitution, her eye following the famous text as her hand refashioned it in Arabic characters. Due to the immediacy of this process, the drawing exhibits a directness not typically found in translation or transliteration. The resulting work is not a readable text from which one might derive a linear narrative like that of the original text. Instead, it is a drawing filled with spelling inconsistencies and Arabic consonants imprecisely substituted for English consonant sounds not present in the Arabic language. Given the circumstances of its creation, the text may even be missing words. Daou herself thinks of the resulting text as the U.S. Constitution being read in an Arabic accent, the words having lost their meaning when taken outside of their American context. The literal implications of the Constitution as a document rather than simply a group of words placed together can only be understood fully in English, and even though Constitution is not a complete iteration of the text in the original document, this drawing requires knowledge of both English and Arabic for any sort of linguistic comprehension.

Divorced from its original meaning, language becomes an object.2 As the drawing progresses along with Daou’s reading of the Constitution, the artist’s mental process of interpreting language becomes increasingly detached from her physical process of writing. With the fundamental essence of the text so unglued, the original meaning disintegrates and the potential for misunderstanding abounds. To use the artist’s own words, in her attempt to create “presence with a lack of presence,” language becomes a sort of “paint.”3 This paint fills the top portion of the frame and acts as a deliberately elusive foil to the void of the hollow cutout in the bottom portion. Although written in pencil, the transcribed letters were treated as permanent—Daou did not make any erasures or revisions, juxtaposing the ephemerality of graphite on paper with the immovability of the marks she had made.

Constitution, one of Daou’s first text-based pieces, marks a fundamental point in her artistic development. As a bilingual, fluent in Arabic and English, who has spent significant portions of her life in Lebanon and the United States, Daou was able in making Constitution to consider both her own linguistic hybridity and the process of translation that takes place in the minds of individuals belonging to more than one culture. With this piece, the artist explains, “…[I am] aiming at the non-culture of people like me. Cultural, not linguistic, translation [occurs] in my head. Translation is constant; some part of you [always] has to be translated.”4 Yet Constitution remains of paramount importance to Daou precisely because its creation allowed her to leave these questions behind, to experience the liberation of making art that does not engage with “identity politics.” The text itself directs both Daou’s hand and the form of the work, thus liberating her from the potential burden of cultural decision-making.

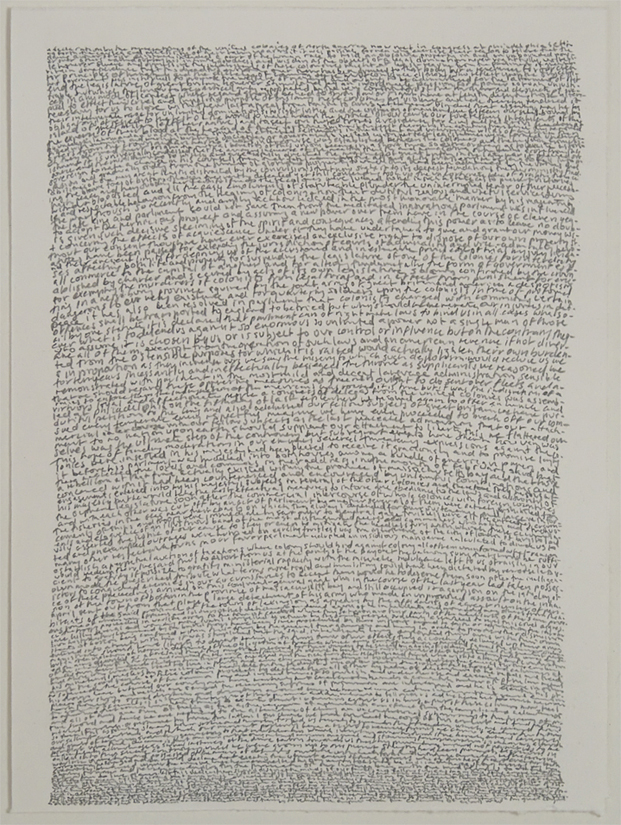

The Declaration of the Cause and the Necessity of Taking Up Arms (2006), made two years after Constitution, similarly detaches the language of a landmark historical document from its original context in order to examine the network of language, culture, and the written word. In this smaller work, however, Daou does not use the Arabic alphabet, instead filling the sheet with a minuscule English version of a document prepared by the Second Continental Congress in 1775. The drawing was originally shown in an exhibition of Daou’s work entitled “America,” in which the artist transcribed twenty documents relating to American history and culture. This series of works attempted to portray the country’s complex and often contradictory history from its founding until the present. As one part of this larger project, Declaration is remarkable in its ability to encourage the viewer to reconsider the original text through the lens of Daou’s handwriting, addressing both personal connections and contemporary relativity. By intentionally disorienting the viewer in this way, the artist locates her work in the space between meaning and non-meaning, maintaining a continuously shifting perspective. Misunderstanding always inversely suggests the possibility for understanding, and in the case of language, it is precisely this possibility that interests Daou.5

Annabel Daou, Book of Hours – one, 2006, artist’s book: graphite on paper with hand binding, 5 x 3 ½ x ½ inches (12.7 x 8.9 x 1.3 cm), closed. © Annabel Daou / Photo: Ellen McDermott

In Book of Hours – one, Daou carefully fills the pages of a blank book with times recorded from the face of a clock. Drawn arrows and numbers visually bridge the gaps between semi-transparent pages, creating sets of timestamps that sometimes fall into seemingly orderly intervals—one hour, one hour plus one minute, etc. Yet this system, while intriguing, resists being decoded fully by viewers. For Daou, this literal “book of hours” documents the passing of time as she experienced it while creating the work. After a collaborator supplied her with 120 individual words that were particularly meaningful to Daou at the time, she habitually spent concentrated blocks of time writing each of those words on paper, one after another. Book of Hours – one maps the times shown on the clock at the start and finish of each 120-word writing cycle. Daou admits that the 120 words were simply “an excuse,” meaning that here she explores the physical process of writing “time” with primary interest in the progression of real time rather than in the content of the words.6 While the contextual information contained in these pages is highly personal to Daou, the artwork also functions universally. For those with no prior knowledge of Daou’s process, the book’s depiction of time can seem innately to relate to the daily life of every human. Viewers may even find themselves contemplating their own activities or rituals associated with these points throughout the day.

With the title Book of Hours, Daou alludes to the late medieval European tradition of books of hours, or prayer books meant for private daily use. These devotional manuscripts guided users through days and seasons with appropriate prayers. Books of hours developed into a genre of sumptuously illustrated and highly personalized luxury objects, but on the most basic level they functioned as calendars. Daou’s artistic process similarly incorporates time-based ritual, but her choice of unadorned materials contrasts with the preciousness of this book’s medieval counterparts. Daou’s reference to the medieval tradition is perhaps similar to her use of historical documents in Constitution and The Declaration of the Cause and the Necessity of Taking Up Arms. In each case she removes the reference from its original context, fundamentally altering its meaning and opening a self-conscious conversation within her work. In Book of Hours – one, this conversation centers on the juxtapositions between the precious and the ordinary, art and anti-art, and the personal and the universal.

Book of Hours – one belongs to a larger body of work that was shown in the artist’s solo exhibition Book of Hours (2007) at Gallery Joe in Philadelphia, even though this particular piece was not part of the show. In addition to another book titled Book of Hours, the exhibition included drawings in which Daou represented one hour by writing the times seen on the face of a clock throughout each of its 60 minutes. A sound piece added to the multi-sensory experience of the installation, with Daou reading each of the 120 words, punctuated by her recitation of the time on the clock. Two confessional gates, as well as the concave ceiling above Book of Hours, which was shown on a pedestal in the position of an altar, reinforced Daou’s attempt to draw a parallel between the ritualistic aspects of her artistic process and those of worship.

Daou has described her artistic process as “trying to find a thread and pull it.”7 In her mind it is this process that is most important: “There is no beginning or end; it will repeat…[It] is not about getting anywhere but finishing the work, and then it can vibrate forever.”8 The notion of time is implicit in both this statement and her artistic practice as a whole. Tempo is always present in Daou’s work, whether represented through the inclusion of timestamps from the face of a clock or borne out in the artist’s conscious progression through the act of transcription. Each work has a different tempo, from the cyclical rhythm of Book of Hours – one to the deliberate forward movement of Daou’s hand in Constitution, at first perhaps staccato and then increasingly fluid. Book of Hours – one marks part of the artist’s larger interest in making objects that are imbued with presence–a presence seated in the tempo of their making and carried out as each work is approached, read, and used independently by viewers.

1. Annabel Daou, unpublished artist’s statement, 2004.

2. Ibid.

3. Annabel Daou, in conversation with the author, June 2011.

4. Ibid.

5. This sentence and the previous one reflect comments made by Daou in Messaouda Bouras, “Interview with Annabel Daou”, www.arteeast.org, 1 October 2006, http://www.arteeast.org/pages/artists/article/71/?artist_id=2.

6. Annabel Daou, in conversation with the author, June 2012.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

Annabel Daou Biography