The art of Ed Ruscha–a seamless combination of elements of commercial design, fine art, and popular culture–evidences the artist’s complex and longstanding relationship with words and language. During the late 1960s, Ruscha turned away from the American vernacular subject matter with which he had been working, including gas stations and other fixtures of the Western built environment, and began focusing on words, which he incorporated into his practice in several ways. Slogans, catch phrases, quotations, and single nouns all appear in Ruscha’s work, having appealed to the artist for either their visual or phonetic forms. As exemplified by Gray Sex(1979), almost all of the single words that Ruscha uses are monosyllabic, evocative, and appreciated as much for their aesthetic qualities as they are for the personal associations and responses they provoke. Sources for these words have included newspapers, radio programs, books, dictionaries, and personal conversations.

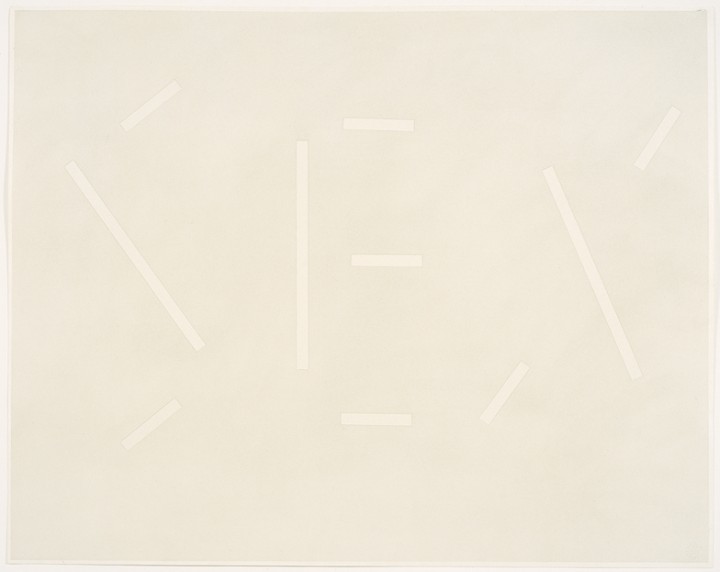

While Ruscha’s rendering within this series of the words l’amour, desire, and fuck may denote undertones of sensuality, the artist insists that there is no one prescribed way to read the drawings. It is integral to Ruscha’s intentions that “the drawing not reflect the meaning of the words”–a goal he achieves in Gray Sex.1 In this drawing, the word SEX is suggested by the disconnected lines that form the three letters. Instead of drawing the word directly, Ruscha used tape to form each letter, applying pastel over the tape before removing it to reveal legible negative spaces. The end result is a work providing no impression of depth: the word is flat and blends into the monochromatic background. Rather then relying on the provocative and erotic associations identified with sex, Ruscha presents a neutralized version. While this depiction is somewhat at odds with the suggestive connotations of the word sex, the artist creates a different context in which to understand multiple meanings of the word. For the artist, definitions are of secondary importance once words have become abstract objects divorced from reference. Much like the early twentieth-century Surrealists, Ruscha is fascinated by the implications of words and by the various associations they elicit, rather than by their literal translations. As Ruscha explains, “I [like] the idea of a word becoming a picture, almost leaving its body,” so that the amorphous form of the word itself can become a blank canvas, upon which a viewer can project his or her own meaning.2

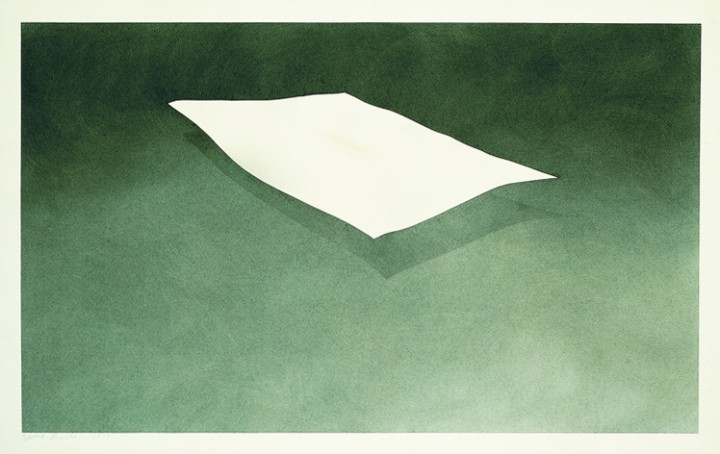

In the early 1970s, Ruscha became dissatisfied with traditional painting and began staining stretched fabrics with various liquids and natural materials, including blood, grass, chocolate, fruits, and eggs.3 In a drawing from this same period, Suspended Sheet Stained with Ivy (1973), Ruscha stained the center of a large sheet of paper with the juice of a crushed ivy plant. Surrounding this central stain, the artist rendered a sheet of paper floating in a darkened dimensional space. On one level, the physical ivy stain lies directly on the drawing surface: it is a sheet stained with ivy. Yet on another level, this is also a drawing of a sheet stained with ivy.4 Here too, the artist plays with perception and the idea of illusion. Ruscha is attracted to things that cannot be explained, ultimately believing that “art has to be something that makes you scratch your head.”5

1. Oliver Berggruen, Ed Ruscha: Ribbon of Words (Vero Beach, FL: The Gallery at Windsor, 2003), iv.

2. Ibid.

3. Sarah Louise Eckhardt, “Ed Ruscha” in Drawings of Choice from a New York Collection, eds. Josef Helfenstein and Jonathan Fineberg (Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum, 2002), 128.

4. Ibid.

5. Richard D. Marshall, Ed Ruscha (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 2003), 135.

Ed Ruscha Biography