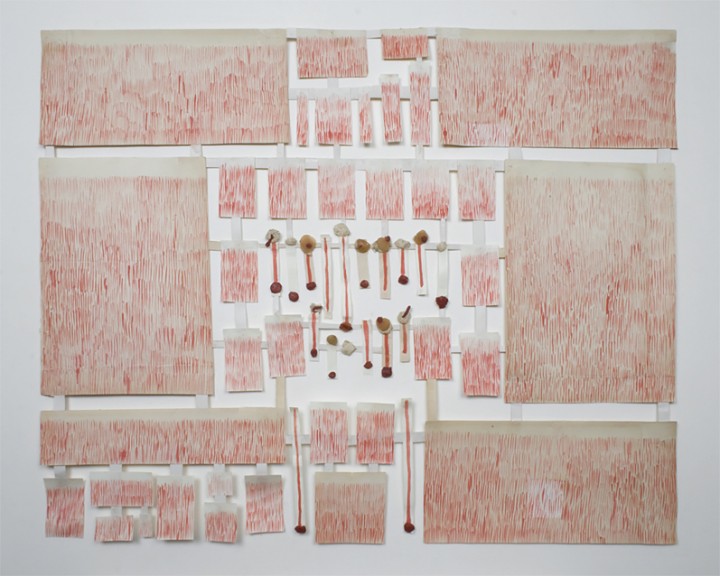

Suzanne Bocanegra’s Brushstrokes in a Victorian Flower Album: Long-Headed Poppy (2000) comes out of a long tradition of using flowers in painting as icons, each varietal indicating a certain psychological state. In the fourth act of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Ophelia says:

There’s fennel for you, and columbines; there’s rue for you, and here’s some for me; … O, you must wear your rue with a difference. There’s a daisy. I would give you some violets, but they wither’d all when my father died.

This passage, uttered in madness, suggests the power of flowers in the Renaissance imagination to signal states of feeling. This “language of flowers” continued to influence the literary imagination for three more centuries. In Victorian England, flower albums and discussions of the meanings of flowers were part of the publishing industry’s “keepsake” series, books intended to be studied and treasured and given as gifts. There was also public discussion of the plants found in famous paintings like William Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World (1853-54), which shows Christ in a weed-filled garden knocking at a door covered with ivy—knocking at the closed door of the human heart. Victorians knew that ivy signified dependence. They knew that Ophelia’s daisy meant innocence and purity and that her fennel signified deceit. The English Pre-Raphaelite painters, with their emphasis on an almost photographic fidelity to the natural world, filled their paintings with plants, assuming that most of their audience could “read” this language of flowers. Indeed, so pervasive was the language of flowers in nineteenth-century English culture that there were gardens devoted to the plants mentioned in Shakespeare’s plays. Such gardens you may find even today in England and America.

Bocanegra’s choice of Henry Terry’s A Victorian Flower Album from 1873 is telling indeed, as is her focus on Terry’s image of the red poppy. Terry’s book is subtitled God’s Floral Gems, Glistening on the Verdant Face of Nature, Collected and Painted in the Summer Evenings of 1873 as a pleasing recreation. For Terry, as for many of his contemporaries, God was evident in the beauties of nature, even if Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, published in 1859, had signaled a very different reading of the natural world.

Bocanegra’s contemporary drawing exists in tension with her Victorian sourcebook; it emerges strongly from a post-Darwinian world where nature is “red in tooth and claw,” as Tennyson feared. Looking at this drawing, do you see the “verdant face of nature”? Are the red poppies in this drawing signs of “God’s floral gems”? Bocanegra has erased the religious super-structure of Terry’s original drawing. And in choosing to depict the red poppy, she has invoked one of the most oft-used emblems of the nineteenth century. To the Victorians the poppy signified pleasure, generally of a sensual nature. The flower recalled Tennyson’s lotos-eaters, who were attracted to a land where it is “always afternoon,” where sensual experiences are all you need for life. But here, some of Bocanegra’s poppies are upside down—for the Victorians, an emblem of the rejection of love. Bocanegra’s assembly of small sheets with vertical red brushstrokes sends no clear signal of love or of a God-ordered universe. Indeed, how do you “read” these marks? What do you “see” in the arrangement of fields of red lines in various shapes and sizes? Why might Bocanegra have placed these brushstrokes in the context of the nineteenth-century flower album, a treasured keepsake for the traditional Victorian?

Suzanne Bocanegra Biography