Nancy Haynes is a conceptual artist. Her practice is to follow an idea, with such care and attention that the artworks resulting from this extended intellectual consciousness often seem to have materialized as a matter of nature. When Haynes’s paintings and drawings arrive at completion, each one comprises not only the artist’s initial thought and the myriad potentialities for the viewer’s perception, but also, knitted somewhere in between, the painstaking work of the object’s making.

Any image generally contains some interpretable component—call it information, whether it takes the form of language, thought, sensation, or visible material element. Access to this information is a primary concern of the viewer when addressing a work of art. More than anything, we want to feel that we can know something about an object.

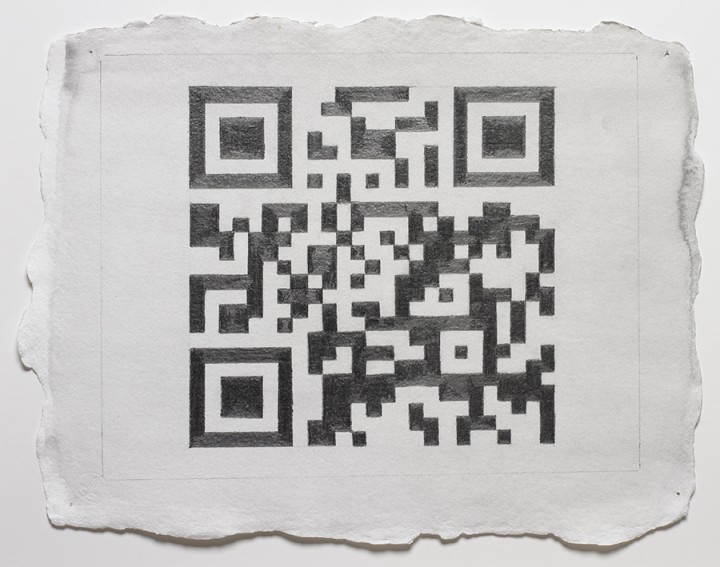

In recent years, Haynes has found herself intrigued by the strange, square-shaped black-and-white images that have appeared with growing frequency on surfaces ranging from the most public to the most intimate—from street posters to the insoles of running shoes. These images, known as Quick Response (QR) codes, were originally developed by programmers in the mid-1990s as a solution to the standard linear bar code’s limited capacity to contain data. Readable in both horizontal and vertical directions, the grid of the QR code allows its creator to convey significantly more valuable information to any user with an appropriate code reader application. Since its inception as a tracking tool in warehouses, the QR code has entered our visual awareness as a primary medium through which we access consumer products, supported in part by the rapid advent of the smartphone in the past decade. Each day, more people know what QR codes are and how to use them; in tandem with this expanding recognition comes expanding access, as increasing numbers of us carry our personal QR code readers at all times.

Haynes knew little of the QR code’s latent function at first.1 Yet in observing the structured modularity of the image and its adherence to the square format—not to mention its reductive palette—Haynes found elements of the modernist grid, the cool seriality of Minimal art, the organic geometry of Mimbres pottery, and the cerebral puzzle of the chessboard. In the occasional alignment of the small black squares, Haynes saw hints of the “plus” shape, or balanced cruciform, which she had used in many of her own early panel constructions. In the QR code’s alternating moments of graphic cohesion and dispersion, Haynes quite intuitively read a sort of contemporary hieroglyphics. Upon learning more about these images, notably about their ability to manifest complex information in a digitally determined visual format, it seemed to Haynes that the QR code would lend itself neatly to conceptual art making. She went to work.

The creator of a QR code determines his or her literal subject matter by selecting as a referent a certain URL, image, or passage of text. A unique visual layout corresponding to that data is then determined by a QR code generator program. Haynes enlists her husband, the sculptor Mike Metz, to print QR codes for the subject matter she chooses, thus depersonalizing any compositional activity. Haynes accepts the generated image as it is presented to her. She cannot alter the composition of the QR code without breaking the inherent digital link to its subject. This restriction is enforced not by conceptual philosophy so much as by function.

Upon receiving the specific QR code image, Haynes works diligently to replicate it on handmade linen paper. She uses a traditional graphite transfer process to map the QR code pattern from computer printout to linen paper sheet, and from this initial tracery she undertakes the darkening of each black square with equal deliberation. This is an exacting activity involving rulers and T-squares. Care is taken to ensure that the edges of the image remain crisp enough to be legible to the QR code reader.

While she works, Haynes is aware of the subject matter to which she is manually linking—but only because she chose it. Beyond that, her literal comprehension of what she draws is quite limited. Here, Haynes writes in an alien language, as if the image is transmitted through her; she can only determine whether her transcription is visually faithful. Knowing what her drawing will say, but not how it will say it, Haynes all the while understands that what she is creating will present a paradox of the unknowable.

When viewing this drawing, perhaps you first notice the sheen of the dense graphite or the nubby texture of the linen paper. Perhaps your eyes linger on the deckled edge of the sheet, the pinholes in each of its four corners, or the distinctive shape of the papermaker’s impression at the lower left. A loose, light wash of grey watercolor has spread to the edges of the paper, the pigment collecting into coastal tidemarks. In places, we can observe the shallow grooves in the graphite where the artist has worked and re-worked the pointed tip of her pencil into the support.

Twenty years ago, a viewer may have looked at this graphic image and wondered what this drawing could possibly communicate, either on its own or in reference to the artist’s conceptual agenda. He or she would have mentally categorized the drawing as abstract or representative, random or composed, worth time spent looking or not—based on what could be seen within it. Yet today, many of us will look at this drawing and experience a distracting sensation of recognition. We recognize immediately that there is something in this drawing to be read and, almost simultaneously, we recognize that we (alone) are incapable of reading it.

Many of us will know where to turn for a translation. Our smartphones see the QR code as a series of binary toggles. Each square can be either dark or light; sufficient contrast and clarity of edges are, to the smartphone, equivalent to legibility. Many of us carry the tool we need to read this drawing right in our pockets. Yet to opt to read the drawing is in some ways to remove ourselves from it: we step back physically in order to frame the QR code in the viewfinder of our smartphone (it is too large to scan up close),2 and in placing a device between our eyes and the object, we extricate ourselves intellectually from the activity of looking at it. We choose between knowing what this object is and knowing what this object says, and either way we each make this choice consciously.

A smartphone can only understand a QR code insofar as it can establish optical contrast. If the edges of the squares are not clear enough to be scanned, the image is rejected. The smartphone’s version of visual criticism is, much like its method of vision, binary—the image functions, or it does not. Imagine that! A smartphone is even wise enough to know its own limitations, and whenever it cannot read an image, it is saddled with no lingering drive toward self-reflection. For now, we humans respond differently, and perhaps it is in part this difference that Haynes’s drawings celebrate.

The beauty of this drawing is that it pauses the viewer just below its surface. Here, Haynes asks us to acknowledge our own partial blindness in the face of this object by making a choice. If we choose to distance ourselves by scanning the drawing with a smartphone, we can access its obscured meaning, and that may be satisfying on a (quite valid) literal level. But if we choose to move past what we cannot know, we allow the object to draw us further inward. We resume our examination of graphite, pigment, and paper—materials we can hope to know directly. The confrontation with the unknowable that Haynes encourages indeed harbors the potential for the great relief of a different kind of understanding: an intimate congress with this remarkable object and with the physicality of drawing.

1. I am grateful to Nancy Haynes for several conversations in 2012 regarding the QR code drawings and what Haynes refers to as their “unknowable quality.”

2. Wynn Kramarsky provided this very helpful observation.

Nancy Haynes Biography

Rachel Nackman Biography