The Most Banal Detail

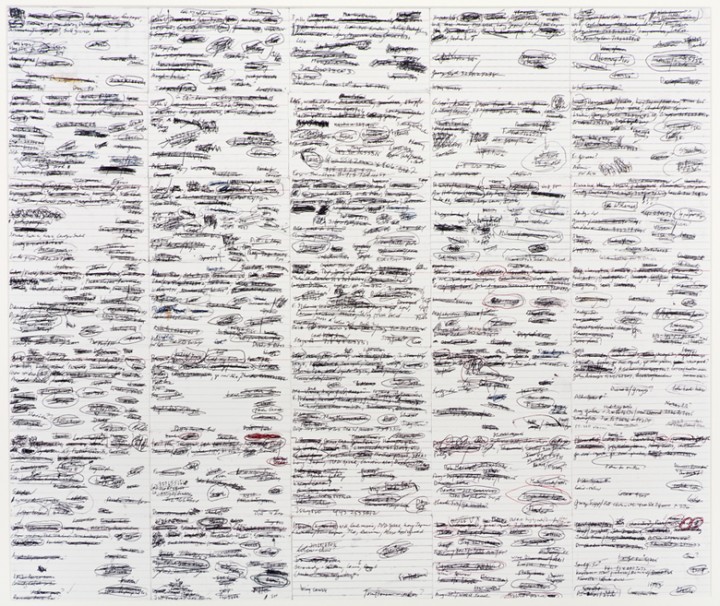

John Waters’s 35 Days shows a grid of index cards on which he wrote his daily plans for 35 random days. Each day, Waters writes an itemized list of tasks on an index card, and as each task is completed, he crosses it out. The first thing you may ask yourself about this piece is, “Why is this art?” A little context might help you understand something more about Waters himself and the project this photograph embodies.

Waters is probably most famous for writing and directing a movie called Hairspray, in which a chubby teenager competes on a dancing show in 1960s Baltimore and racially integrates her community in the process. The second thing he’s most famous for is getting the actor Divine to eat dog excrement in a film called Pink Flamingos. There are lots of things that Waters has done, though, that have flown under the radar of mainstream America. He’s a very entertaining writer, a collector of artwork by such notable artists as Cy Twombly and Mike Kelley, a stand-up comedian, and a hobbyist hitchhiker. He’s the leader of a renegade band of actors known as the Dreamlanders, many of whom have pre-purchased tombstones in an area of a Baltimore graveyard they refer to as Disgraceland. He’s a justice activist who has repeatedly petitioned to get repentant criminals out of prison. He’s been sued for obscenity in multiple countries and has never won a case. He’s a provocateur, a raconteur, and an all-around hero of the most “under” of the underdogs in our society. All this from a man who was raised to be a good Catholic boy in upper-middle-class Lutherville, Maryland!

If this description hasn’t intrigued you, I’d like to add that he’s arguably one of the funniest people alive. If you’d like proof, you have only to check YouTube for the public service announcement he made for movie theaters: “No Smoking.” Smoking a cigarette throughout the announcement, he purrs and drawls: “I’m supposed to announce that there is no smoking in this theater, which I think is one of the most ridiculous things I’ve ever heard of in my life. How can anyone sit through the length of a film, and especially a European film, and not have a cigarette? But–don’t you wish you had one right now? Mmmmmmmmmm-mmm-mmm-mm.” He takes an enormous drag off his cigarette and then French-inhales the smoke right back up his nose, taunting the audience.

Here’s the kicker about this work of art. This piece is a record of the days and tasks of a man who is perhaps the preeminent symbol of anti-bourgeois, countercultural effrontery in American film, and he’s the most organized fellow! Each of these 35 index cards represents one day’s tasks, all neatly written down in a list; each task is crossed off upon its completion. Our culture often promotes particular notions about what it means to be an artist, usually a collection of stereotypes: the artist must be a moody, brilliant person led by flashes of inspiration and sudden whims. He can’t possibly be methodical, ordinary, or bound by routine in any way. His genius comes from his unconventional way of life. For example, the Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí claimed to sleep for brief moments with a key in his hand, which would bang into a pie plate once his sleeping hand released its hold. The pie plate’s clanging noise would wake him up, and he would continue his madcap pace of painting and profound psychological exploration. (Dalí himself promoted this idea, perhaps in a reaction of deep shame to his extremely traditional–and excellent–art education. How could one possibly be a Surrealist with a conventional life?)

As a writer myself, I know that any creative project I want to accomplish takes a lot more than inspiration. It also necessitates careful planning, deep thought, organization, hard work, and revision. Art doesn’t really make itself out of some magic fairy dust exuded (or, for that matter, snorted) by naturally talented artists. It’s a process, a plan, and a system of execution. Even obscene art needs a plan. That plan is what Waters allows us to see and understand in this work of art–which encompasses not only the visual aspects of the photograph, but the experiential work that those little index cards represent. Each of the 35 cards is the symbol of a day in the life of this artist–his plan, his system of collating and prioritizing the things he needs to do to make the art-machine go. As he wrote about the work of Cy Twombly, “This exclusive, violent, erotic handwriting that may seem illegible to others can be read if you just give it a chance.”1 This statement applies equally to Waters’s work here. Look closely. Under the spastic scribbling and crossing out, you can see some of the details of his days. Among them are friends to call, speeches to develop, and even “3 pills.” Try to find all the references to cameras. You might even discover your own name beside Ricki’s and Patty’s. I only wish that the note “Call NY apt for Susan” referred to me! You can ask yourself, where did that red pen come from, and does it designate something important, or did it just come to hand? What goes on in Waters’s brain, and how does he put this life together, and why did he turn out so deliciously different from the rest of us if his day, just like ours, merely depends on a little list on an index card?

Or you could just ask yourself, as Waters does in the essay “Roommates” in his 2010 book Role Models, “Isn’t art supposed to transpose even the most banal detail of our lives?”

1. John Waters, Role Models (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2010), 247.

John Waters Biography