Using the Typewriter as a Lathe or Saw:1 Carl Andre’s Poetry

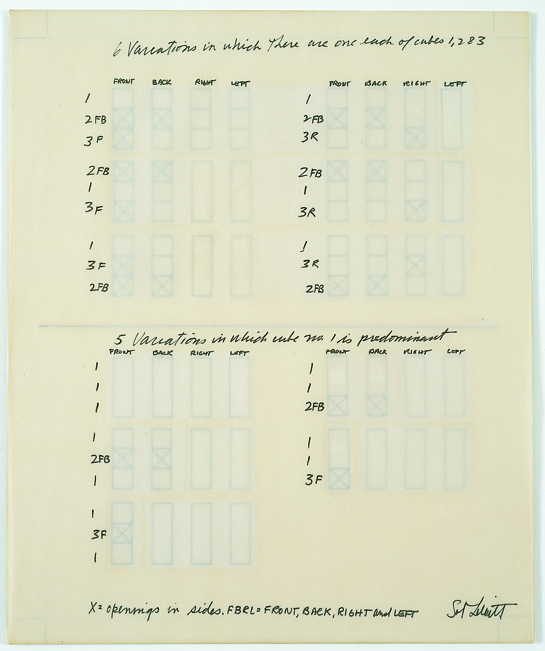

Carl Andre is best known for the gridded floor pieces he developed in the mid-1960s—flat arrangements of identical unjoined units of industrial material, which defy sculpture’s conventional verticality and stability (see 144 Lead Square, 1969). Also at that time, he began to describe sculpture in novel terms; he conceived of the object as a cut in space and the artwork as a place or site.2 Such radical forms and ideas seem to have appeared quite suddenly. They bear little resemblance to Andre’s totemic Brancusi-esque works of 1958–59 and he had made little sculpture in the interim. To explain his abrupt conceptual and formal advances, scholars have often contented themselves with biographical myths propagated by the artist himself. For example, Andre’s use of “clastic” (i.e. unjoined) units is often credited to his experience working as a brakeman on the Pennsylvania Railroad from 1960–64. In another origin story, Andre devised the concept of flat sculpture while canoeing on a lake in New Hampshire, where he suddenly “realized his sculpture had to be as level as the water.”3 Both of these anecdotes, which Andre employed to clarify his unconventional sculpture, have been canonized as quasi-religious epiphanies explaining the artist’s major formal and conceptual shift.

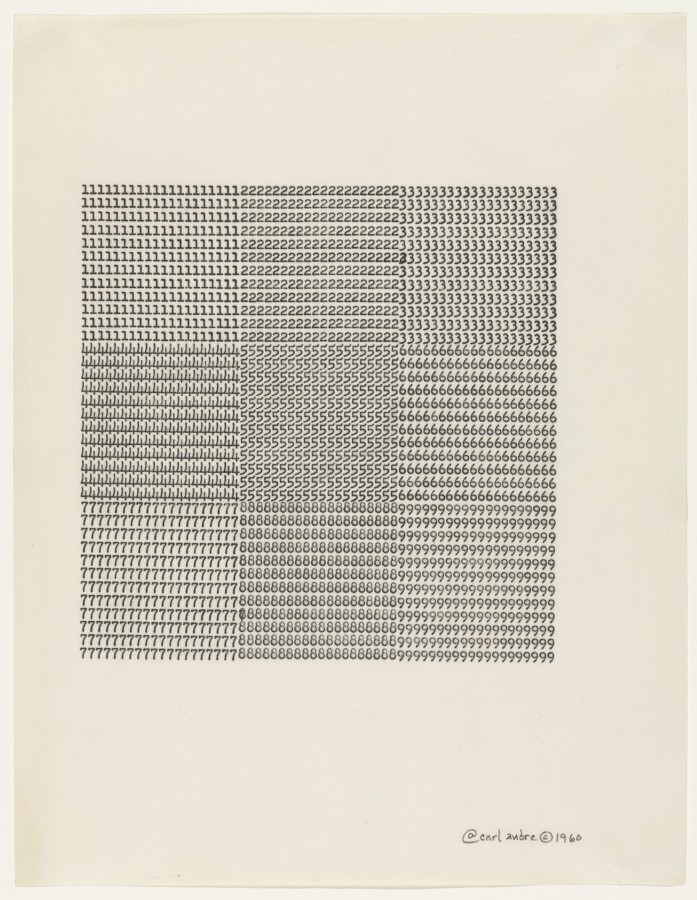

However, we need not be satisfied by reductive biographical explanations to characterize Andre’s sculptural development. While he produced little sculpture in 1960–64, he was far from inactive creatively. During this period, he tirelessly explored unconventional forms of poetry, a pursuit that served as a laboratory for experimentation through which he formulated some of his most innovative artistic forms and concepts.4 Before his sculptural grids, Andre devised text-based grids like Untitled (1960). The mechanical found grid of the typewriter was the system within which Andre worked as a poet, applying numbers and words as he would later apply squares of copper, lead, and magnesium. In his 100 Sonnets (1963), Andre even made grids of the words “copper,” “lead,” and “magnesium” before he did so sculpturally. Andre’s refusal to connect his words in sentences (i.e. his denial of syntax as communicative glue) is a direct precursor to his rejection of joints or rivets to connect his clastic units, which would have stabilized his sculptures.5

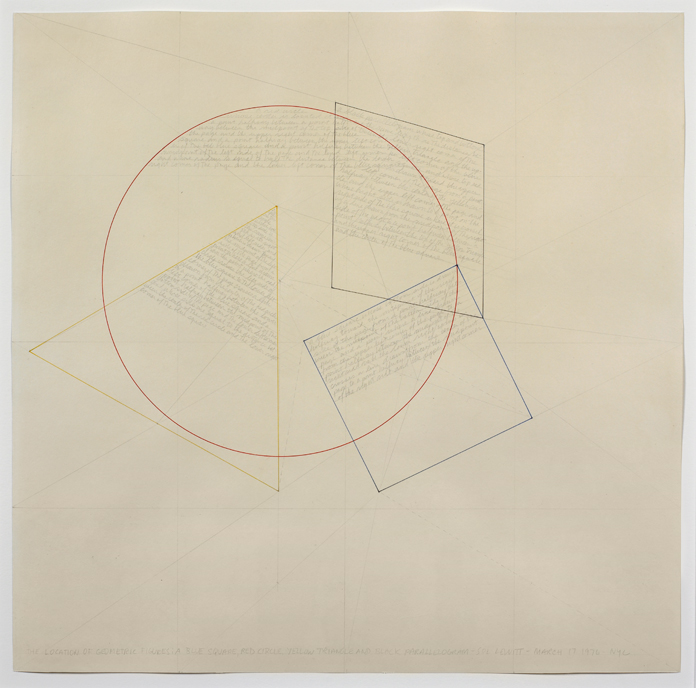

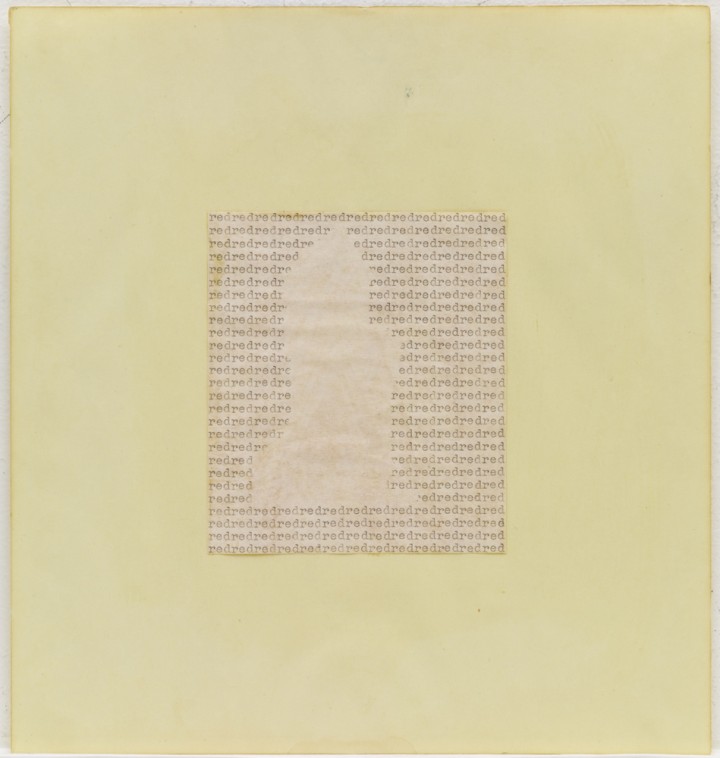

In Andre’s early poetry we find not only morphological precedents to his mature sculpture (grids, scatters, rows, and clastic units), but also the origins of conceptual tenets often attributed to the 1965–67 period. One such breakthrough is the idea of the object as a cut in space, which inverts our traditional notion of positive and negative space; Andre explained, “A thing is a hole in a thing it is not.”6 The seed of this principle is visible in his poetry before it appears in his sculpture. In 1963, he began work on the poem American Drill, in which the text is demarcated by the white of the page within a field of black ink, thereby reversing the typical positive presence of typed words on the negative space of the page. This is a direct precedent to his installation Cuts (1967), in which a single layer of concrete capstones covered the floor of the Dwan Gallery, with six rectangular recesses corresponding to his earlier sculpture Equivalents (1966). Although bearing a slightly later date, red red (1967) also comprises a field of text serving as the background, while the white of the page articulates a foregrounded figure.

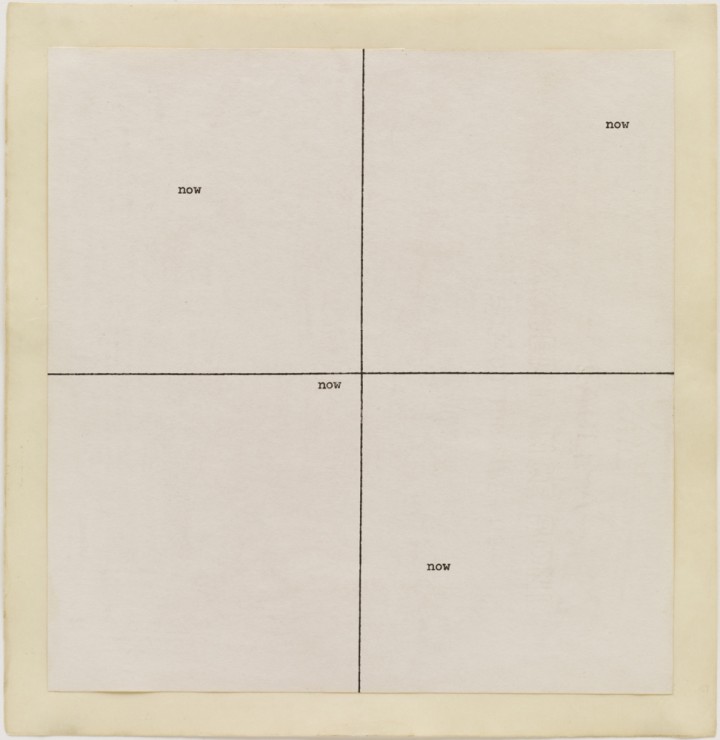

The third work included in this exhibition, now now (1967), exemplifies another central concept often attributed to Andre’s sculpture, but first found in his poetry of the early 1960s: artwork as place or site. This idea activates the viewer’s awareness that the page and the gallery, while often neglected as neutral backgrounds, are forceful components of a work of art. In now now, Andre shows four iterations that are ostensibly identical: a single word now within a square. However, he clearly demonstrates that the word’s placement within space affects how one sees it. As a sculptor, Andre similarly draws attention to the space of the gallery by not only replicating the floor with his flat sculptures and encouraging viewers to physically traverse these pieces, but also by situating his works so that they have a dynamic relationship with the space they inhabit; they jut out from the wall, nestle into corners, and occupy the middle of the room sanspedestal.

Andre’s text-based work belongs to the phenomenon of artists’ writings of the 1960s and should be studied alongside and in contrast to those of Robert Smithson, Mel Bochner, Robert Morris, and Donald Judd, to name a few. As study of Andre’s poetry increases, we should consider it not as a facile equivalent to his sculpture, but rather ought to situate it more carefully on a continuum in his development as an artist.

1. When explaining his poetry to Robert Morris in 1975, Carl Andre stated, “I have used the typewriter as a machine or lathe or saw, to apply letters on the page. I really do feel very tactile using a typewriter.” Cited in Carl Andre, Cuts: Texts 1959–2004, ed. James Meyer (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005), 212.

2. Andre articulated both the “use of the material as a cut in space” and “sculpture as place” in David Bourdon, “The Razed Sites of Carl Andre” Artforum 5 (October 1966): 15.

3. Andre underscored the biographical stories of both the railroad and the lake to Bourdon in ibid, 15-17.

4. Attention has been paid to Andre’s poetry throughout his career. Recent studies include: Liz Kotz, Words to Be Looked At: Language in 1960s Art (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007); Dominic Rahtz, “Literality and Absence of Self in the Work of Carl Andre” Oxford Art Journal (27, 1 2004): 61-78; Alistair Rider, Carl Andre: Things and Their Elements (New York: Phaidon Press, 2011); and James Meyer in Cuts: Texts 1959–2004.

5. Andre’s obliteration of meaning and communication in his poetry has been discussed by Robert Smithson “A Museum of Language in the Vicinity of Art” Art International (March 1968), 21; and Kotz, 142.

6. Andre in Bradford College Symposium in 1968; cited in Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 (Berkeley: University of California press, 1997), 40.

Carl Andre Biography