Polaris is a star that goes by many names: North Star, Northern Star, Pole Star, and most significantly, Guiding Star. This last moniker points to the star’s remarkable role in guiding countless sailors, travelers, and adventurous souls across the earth. Polaris remains nearly motionless in the sky as the stars around it rotate with the progression of the night, making it the ideal marker for navigation through an otherwise unnavigable world, in which nothing, not even the sky itself, stands still. By choosing Polaris as the title and subject of these drawings, Lawrence Weiner draws upon the full weight of the history and connotations of this celestial entity. But by a sideways allusion to the star’s most important quality — stability — Weiner also redirects meaning toward more slippery terrain.

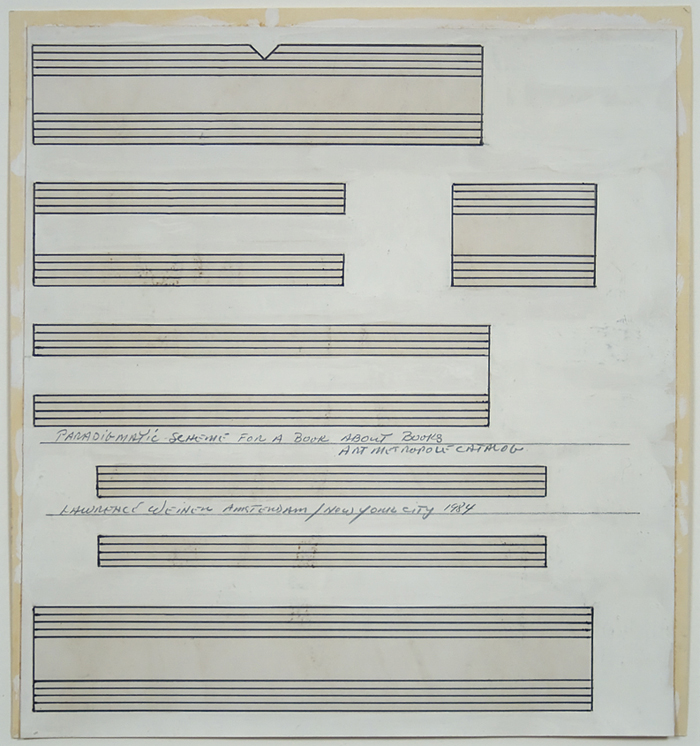

Instability is characteristic of the artist, who is best known for his conceptual statements, words, phrases, and directions displayed across walls and other surfaces. For Weiner, language is not merely text or decorative motif – it is a form of sculpture unto itself. The meaning of his words is never stable; depending on context they take on various significances. As Weiner’s sculptures are constantly installed in new locations, they are perceptually elusive, never succumbing to a singular distillation of meaning. Moreover, these words, although physically manifested as pigment on a surface, are meant to be transformed into new forms entirely. According to Weiner, “The work I do is designed for translation. It’s the exact opposite of what poetry is.”1 This statement indicates that Polaris is more than a clever combination of words and shapes; it is a schematic diagram, an illustrated map, or, like the North Star itself, a guide.

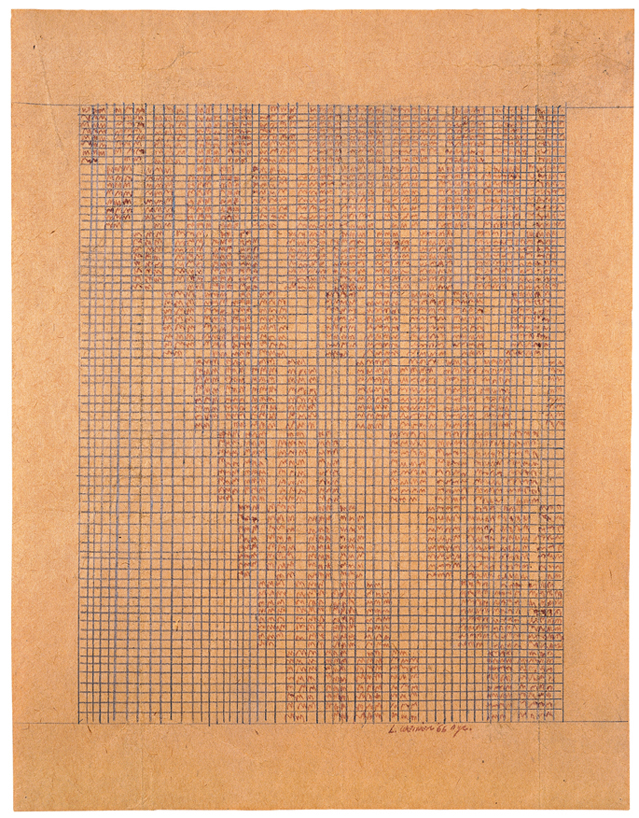

Polaris seems to pulsate: arrows and ovals appear hastily drawn, scrappy lines suggest a quickly moving hand and a need for speed. This quality lends a precariousness to the work, as if Weiner needed to capture the movement of the stars as quickly as possible, lest they disappear from the sky. Cut-out holes further destabilize the subject matter and composition – instead of seeing the most geographically constant star, Polaris, we have only negative space. In contrast to these empty holes and quickly drawn lines, the blue and red parentheses along with the phrase STARS DON’T STAND STILL IN THE SKY seem to maintain a sense of weightiness. The boldly stenciled letters and thick colored brackets look firmly placed on the paper, an appearance somewhat at odds with the perceived meaning of the words themselves.

What does it mean when Polaris has lost its stability and, by extension, its guiding ability? Weiner takes us into existential territory, making us question concepts of reliability and consistency, as well as the very truths that make up our reality. There is a certain amount of liberation in shaking off limits and releasing reality from the boundaries of our expectations. In this way, Polaris is not merely a geographical guide. It is a path to alternative ways of thinking and a model for expanding the scope of our minds to encompass greater possibilities for understanding the world around us.

1. Quoted in Phyllis Rosenzweig, Lawrence Weiner: Works with the Passage of Time (Washington, D.C.: Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden, 1990), n.p.

Lawrence Weiner Biography

Sarah Zabrodski Biography