Russell Crotty’s work seems self-evidently “amateur,” in the etymological sense of the term1 : he is a surfer who doodles the surf, a hobbyist astronomer who sketches the stars. Crotty’s transcription of the natural world conveys a straightforward fascination with its marvels: crashing waves, haunting landscapes, and sublime universes. Yet a drawing such as Hale Bopp Over Acid Canyon (1999) conceals a complex infrastructure. As is often true of talented artists, apparent simplicity is achieved only through technical mastery and conceptual diligence.

Hale Bopp was one of the brightest comets ever recorded. Although Crotty’s tondo format mimics the view through the telescope he uses to stargaze, Hale Bopp was in fact perceptible by the naked eye from May 1996 to December 1997. The artist has captured the celestial phenomenon as he may have seen it over Acid Canyon, a county park in Los Alamos, California.

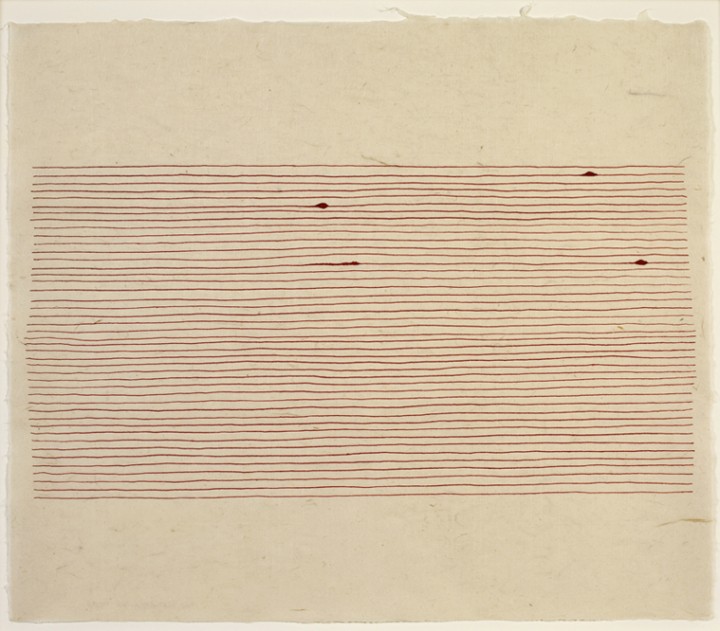

In Crotty’s drawing, he has reversed the intuitive behavior of matter. To human eyes, outer space is always the backdrop, the emptiness against which focal points are determined. But in Hale Bopp Over Acid Canyon the comet becomes negative space, and the dark sky is filled with the artist’s residual ink. Crotty circumscribes the comet and accompanying stars, defining them through the absence of ballpoint pen marks. Instead of amenably fading into the background, Crotty’s empty spaces push forward, asserting presence amidst the tightly controlled marks of a concentrated scribble. At the bottom of the drawing, that darkness—not the uniform jet-black of comic books but the gradated expanse visible in every night’s sky—collides into teeming handwritten reiterations of the drawing’s title. Whether intended as a continuation of space or an indicator of the transition to land, this textual element corroborates the work’s subjective existence: this is not a photograph of the comet, but a record of it translated by the idiosyncratic human observer.

Crotty is well aware that his drawings could hardly serve astronomers attempting elaborate calculations. He has explained, “At some point I just start putting stars in. It goes from being ardently empirical to something else: it’s not so much that these drawings have a foundation in reality as that they have an experience in reality.”2 David Frankel aptly summarizes Crotty’s approach as “a humanistic version of science, perhaps informed by the Victorian gentleman astronomer.”3 Not only is the artist’s approach humanistic—in the sense that he emphasizes the perception of astral events over the gathering of quantifiable data—but his naturalist’s interests provide the occasion for philosophical ruminations.

Our perception of events in outer space is always delayed; it could be called “reactionary.” Crotty has alluded to his fascination with the element of time as it affects his astronomical observations: “A telescope is like a time machine. When you look at Saturn you’re looking at light that’s an hour and a half old. When you’re looking at some galaxies, you’re looking at something 50 million light years away.”4 In Hale Bopp Over Acid Canyon, he synthesizes and tangles the complicated relationship between humanity and the celestial, a relationship that challenges the strictures of time. Herein is the time distant past, which the stars experienced prior to our viewing of them; the time present, as the comet streaks over the canyon; and the time extended, during which the artist laboriously writes out his lines of text. The work sets forth its own history, and the layers of experience were all Crotty’s before they were belatedly relayed to us. The stars that had shone long before they shined to Crotty are now shown to us. The comet that once streaked now streaks, and the artist wrote words that we now read.

Crotty has described how, through observation, “You start realizing [the] distances and ages of these things.”5 “These things” encompasses the natural and ancient systems whose appeal to the artist preceded his idiosyncratic artistic treatment of them. He admits a “bit of sentimentality” about “deep time,” which substantiates the amare root of his amateurism. But Crotty’s love, rendered with a schoolboy’s delight, is actually the devotion of a mature artist, whose homage to his muses takes the form of beautiful and complicated visual explorations of the natural world: finite, but, from our perspective, boundless.

1. amateur, n. Etymology: < French amateur < Latin amātōr-em, n. of agent < amā-re to love. One who loves or is fond of; one who has a taste for anything. Oxford English Dictionary, 2012.

2. Quoted in David Frankel, “Russell Crotty” in Russell Crotty (Seattle: Marquand Books, 2006): 8.

3. Frankel, “Russell Crotty,” 10.

4. Ibid, 12.

5. In Ian Berry, “A Dialogue with Karen Arm, Russell Crotty, and John Torreano at the Tang Museum on February 5, 2005” in A Very Liquid Heaven by Ian Berry, Margo Mensing, and Mary Crone Odekon (Saratoga Springs, New York: The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, 2005): 125.

Russell Crotty Biography