In the 1950s, San Francisco was experiencing a renaissance led by a vibrant counter culture that spanned the literary, film, and artistic communities, with many participants active in more than one medium. In Secret Exhibition: Six California Artists of the Cold War Era, Rebecca Solnit’s exploration of San Francisco’s mid-century artistic subculture, she notes that the rebellious spirit that would sweep the country in the 1960s as a reaction to the repressive culture of the ‘50s had its origins in San Francisco. As she writes, “the art of this California underground constituted an assault on the neat boundaries of formalism and convention, and its tactics included explicit language and imagery and forays into mixed and new media.”1

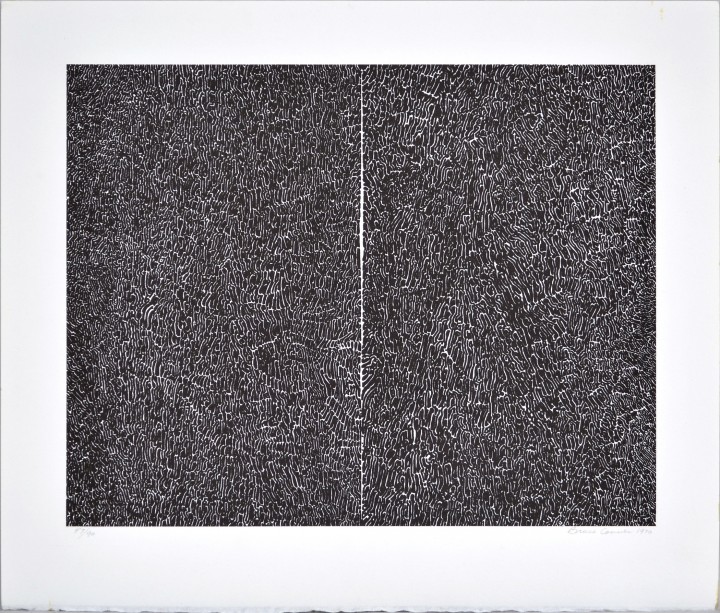

Bruce Conner embodied the spirit of this time, working in a wide variety of mediums: film, sculpture, collage, drawing, painting, printmaking, photography, and assemblage. #114 is from a 1970 edition of lithographs on paper, reproducing the intricate black and white drawings that he made in the 1960s using a felt-tipped pen, then a relatively recent innovation. The artwork’s overall edge-to-edge surface and gestural marks call to mind the visual syntax of Abstract Expressionism, while its arrangement suggests the pages of a book and collaborative relationships between artists and writers. Indeed, Book Pages is the title of a similar felt-tipped pen drawing that resembles this one. The white and black lines mimic scribbled writing, though there is a distinct difference between Conner’s lexicon and the similar investigations included in this exhibition by Frank Badur, Elena del Rivero, and Mary McDonnell. In these works, other forms of mark-making are substituted for writing, but in ways that facilitate their interpretation as writing. For example, the marks are distinct from their backgrounds, and the convention of leaving margins around the writing is maintained. Although we can’t actually read what the artists have “written,” the works suggest that we might be able to do so. Conner abandons these conventions. His marks meander across the page, extending all the way to the edges. He creates no distinction between the “writing” and the background, such that we can barely determine what constitutes each, whereas Badur, del Rivero, and McDonnell offer a lexis that stands in for the personal intimacy of writing.

At first glance, the image evokes certain frames in Stan Brakhage’s 1963 hand-processed experimental film Mothlight, in which moth’s wings pressed between two layers of celluloid reveal their intricate webbing. Conner was a student at the University of Colorado at Boulder when he met Brakhage, who had recently returned to Colorado from San Francisco after lodging for several years with Jess and Robert Duncan. Brakhage, too, had participated in San Francisco’s cross-pollinated arts scene and was an early pioneer of American experimental film.

The black and white palette recalls Conner’s own work in experimental film. Given the prohibitive expense of purchasing, shooting, and developing new film, Conner worked entirely from found footage using old newsreels, other existing films, and the discarded leaders that he was able to collect from developers, to which he added a completely unrelated soundtrack. Conner made about two dozen of these non-narrative films, including 1958’s A MOVIE; a 1960 collaboration with Jess, THE FORTY AND ONE NIGHTS OR JESS’ DIDACTIC NICKELODEON which focused on Jess’s collages; 1961’s COSMIC RAY; and 1967’s REPORT, the heavily politicized satire of the Kennedy assassination and media culture. He experimented with other hand-processed image-making techniques, such as puncturing, slicing, and scratching the film.

These techniques were intended to breach the conventions of Hollywood editing, in which editing is meant to be invisible, enabling the viewer to seamlessly enter the world of the film, suspending any disbelief that what we are watching is a construction. As film scholar Bill Nichols notes, experimental and structural films mobilize the medium of film itself to underscore an ideological agenda: the radical form “distances viewers from a purely realist style and engages them in the process of understanding how productive, material forces actually construct a social reality.”2 The radical politics of the ‘60s, characterized by civil rights struggles for African Americans, women, and gays and lesbians, was grounded in exposing the falsity of many ideological constructs previously upheld as natural and inevitable. By conflating notions of surface and depth, and by flattening the binary relationships that Badur, del Rivero, and McDonnell preserve, Conner invites the viewer to consider these relations anew.

1. Rebecca Solnit, Secret Exhibition: Six California Artists of the Cold War Era (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1990), x.

2. Bill Nichols, Engaging Cinema (New York: W.W. Norton, 2010), 315.