Post-war America saw the notable development of many close relationships between painters and poets. Joe Brainard remains among the few figures of that fruitful period remembered for shifting deftly between visual and narrative media, and for playing both roles successfully. Living in New York City in the 1960s and ’70s, Brainard became part of a thriving group of creative thinkers – visual artists and poets, many of them gay men – whose very public work made intimate address its central concern. Yet legal and social mandate required these men to obfuscate the details of their most intimate associations and desires, lest they expose themselves as gay. Collage became a defining mode of expression for these artists.

We associate particular concepts with certain words and images, but the flexible medium of collage allows artists to recontextualize both image and text, producing new connections and meanings. Brainard’s Matches (1975) features a horseracing ticket pasted beneath a book of matches, mostly spent, with gouache dampening or accentuating particular elements of the composition. The combination of the spent matches and ticket imply the duration of an activity – perhaps a day at the track – and thus the artwork becomes an eminently recognizable record of a moment of leisure passed.

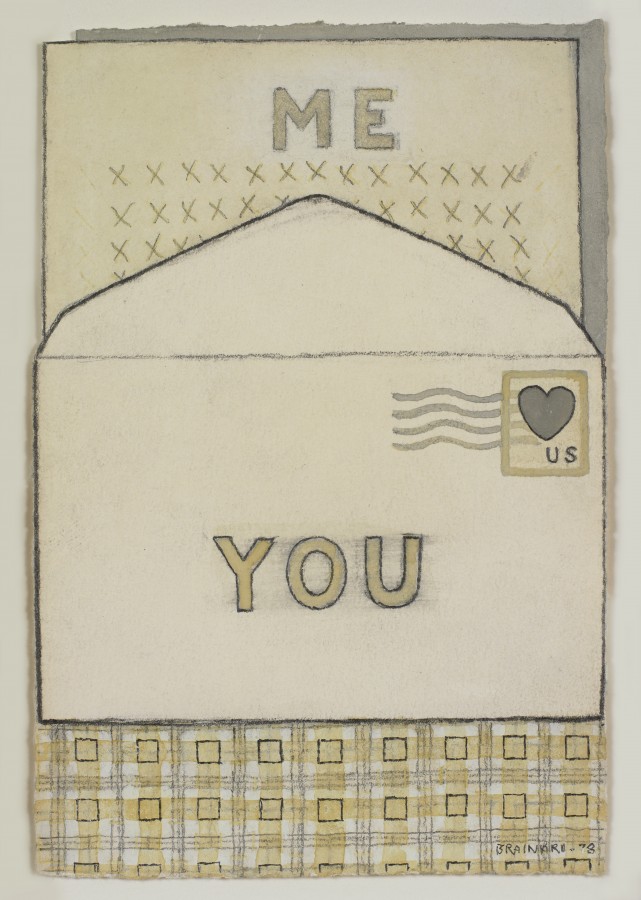

Brainard’s greatest strength lay in the production of artworks that, like Matches, suggest a familiarity or intimacy that cannot be completely articulated. In Untitled (1978), Brainard cultivates a sense of intimacy among artist, object, and audience with what appears to be an outgoing letter to a universal recipient – you. That the recipient of the letter is simply you implicates a romantic relationship, without regard to the gender of the recipient. This presents a subtle challenge to the fixedness of normative male–female sexuality. By producing a work that looks like a letter, Brainard situates himself within the vernacular of mail art – a network of mostly gay male artists and their patrons, which began to circulate small-scale work through the United States Postal Service during the post-war period. Untitled, in particular, points to the artist’s lasting interest in fostering community through communication, whether subtle or overt.

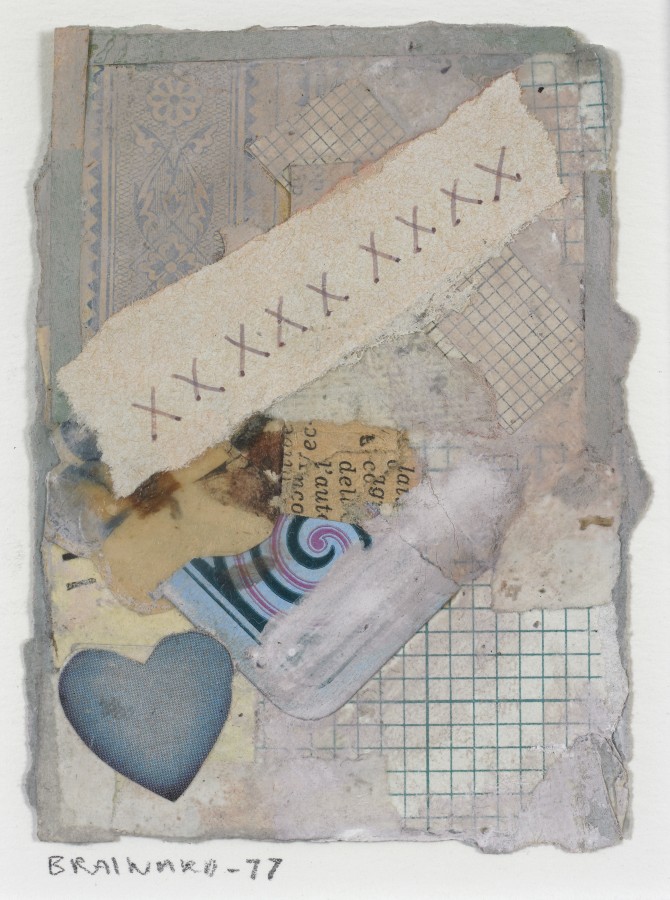

In Untitled (XXX…) (1977), Brainard has collaged a blue heart and a strip of handwritten X’s over assorted patterned papers. We assume that this strip of X’s stands in for an emotive message, but the meaning of this message is not communicated and cannot be accessed; the X’s only insinuate intimate expression to the viewer. The jumble of collaged papers serving as background displays both decorative floral patterns and straitlaced grids, a formal juxtaposition that produces a subtle tension underneath the opaque X’s. It is through careful consideration of these three works as a whole that we can come to understand how Brainard, engaged as he was with questions of language, intimacy, and communication, found the conceptual mobility of collage and universally-addressed language so compelling as he traversed the challenges of what could and could not be said.

Joe Brainard Biography

Cat Dawson Biography