Two Palms had been open for less than a year when I was invited to produce this small series of embossed prints with Sol LeWitt in 1994. Sally Kramarsky called me and asked if there was an artist with whom I could secretly produce a print for Wynn Kramarsky’s 70th birthday. Since Wynn and I were both in love with Sol’s work, it seemed natural to approach Sol for this project. He readily agreed, with his usual economy of language: he said yes, and the matter was settled.

Having recently embarked on a print project with Mel Bochner, my former professor at the Yale University School of Art, I was thrilled to be working simultaneously with two revered pioneers of minimal and conceptual art. Seasoned pros at project-oriented collaborations, both artists instantly knew how to take advantage of the new set of tools I offered and to make something unique within their oeuvre.

The first time he visited my studio, Sol quietly ambled about, feeling paintbrushes and picking up printing plates. He was fiercely intellectual, but notoriously reserved. After a few minutes, he stopped and gazed at the monolithic industrial hydraulic press occupying an altar-like position in the room. “Could you show me how it works?” I ran the press up and down so he could see how the lower platen came straight up and contacted the top platen, the needle on the pressure gauge climbing slowly to 350 tons.

Sol went to the edge of the room and peered through his glasses at a freshly printed Bochner piece pinned to the wall. The print had deep embossment and was caked with juicy red ink. Sol couldn’t resist the impulse to feel its surface. Of course the ink was wet, and he smeared the line. “Sorry,” he said. “Sorry,” I replied, handing him a paper towel. “I should have warned you it was wet.” (I still have the smudged Bochner print.) Sol looked around a bit more while wiping his hand, and he felt through the raw slabs of thick white handmade paper made especially for us by Twinrocker. “I have some ideas; I know what I want to do,” he said.

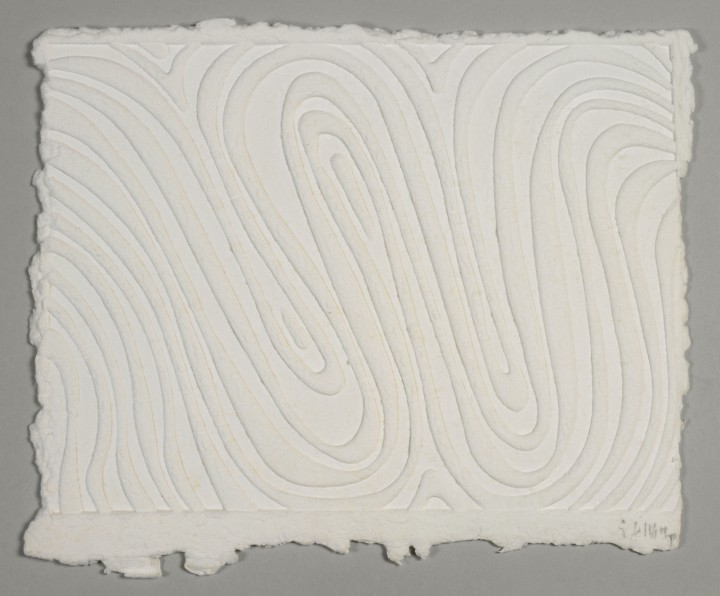

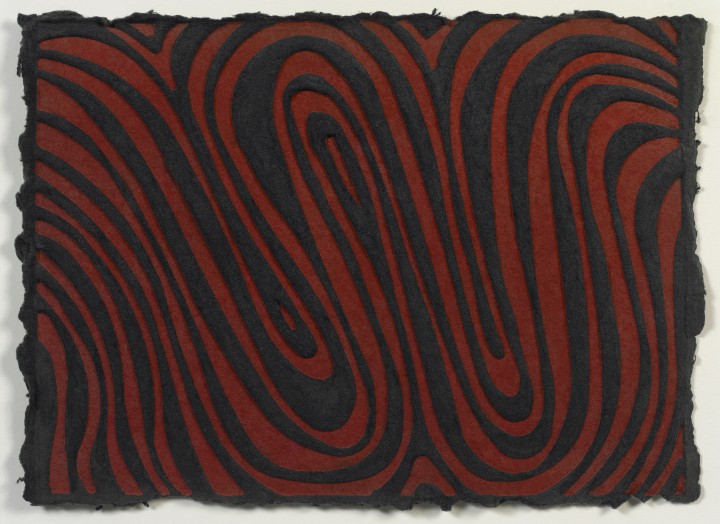

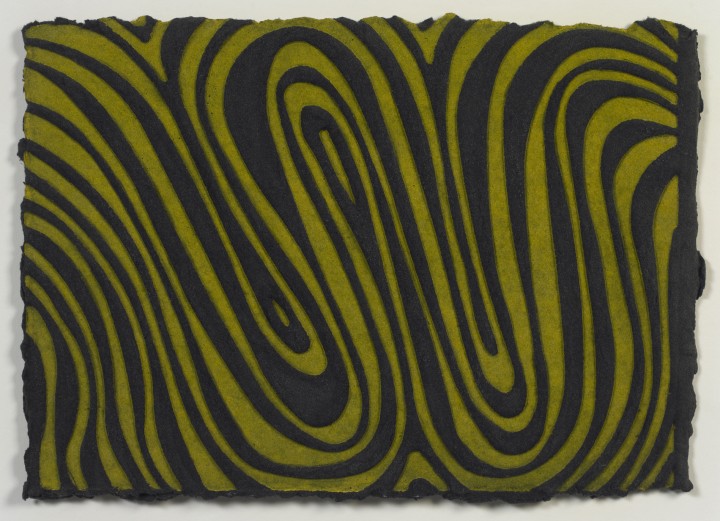

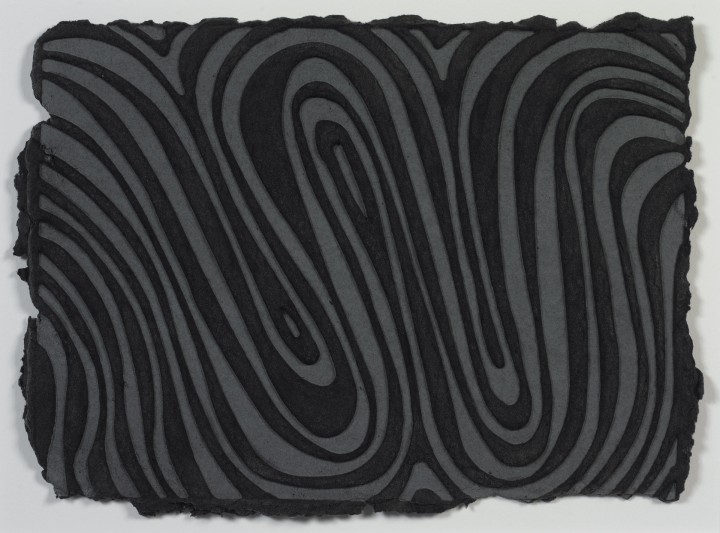

A few days later, I arrived at the studio early in the morning, and a drawing lay waiting in the inbox of my fax machine. It had arrived at around 6 A.M. Wavy lines formed a W with color notations inside the lines. Instructions were added in the lower margin, along with his signature: solwith a circle drawn around it. We were to dye paper certain colors, create a deeply engraved plate based on his drawing, roll the plate with colored ink, and print it on the hydraulic press. Sol knew the colored paper would push down into the engraved grooves and, when hung on the wall, would physically pop off.

Producing the plates was a problem; this was before the use of lasers to cut plates was a practical consideration. Hand carving plates from wood was an option, but tests showed us that the wood would break down quickly under pressure from the hydraulic press. It was not a solution for an edition. Finally, we had an engineer make computer-aided design (CAD) renderings of Sol’s drawings, and using these he generated a tool path for a computer-controlled milling machine. The plates were precisely and deeply milled out of aluminum. Today our in-house laser engraving machines allow us to achieve the same results, only faster and cheaper.

Sol made use of our unique press and our custom paper to add physicality to the visual opulence of his original drawing. When he came to see the proofs, he again ran his hand over the surface of the print, feeling every crevice and raising it up to his nose, smelling the dye. The materiality of the object seemed to give him pleasure. He told me he was also working on an installation project for the Lighthouse International, a research center for the blind in New York City, and he wanted to make a piece that we could see and the blind could feel.1

In light of his earlier rational, ordered, idea-driven works, with written instructions referencing the path from idea to artwork, I asked Sol if he was now somehow embracing a kind of chaos theory in all its intelligible disorder. Perhaps, in his wizened years, he was appealing more to the eye than to the mind? He responded simply, “No.”

1. Sol constructed his Styrofoam Installation #32 behind the information desk at the Lighthouse on East 59th Street in 1996.

Sol LeWitt Biography