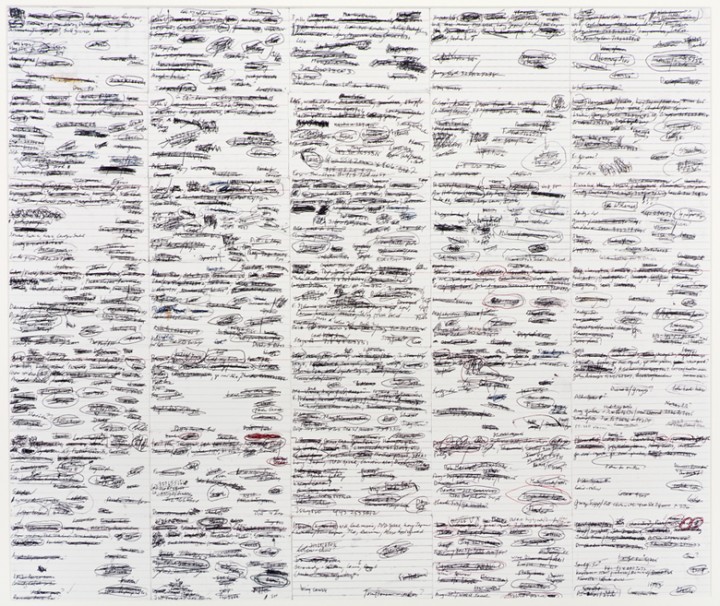

35 Days, from 2003, is a photographic print of a drawing comprised of thirty-five index cards. Each card appears to be a random blast of names, phone numbers, and references. It is unclear if there is a hierarchy or order to how the information is written onto each card. The discord of each card is amplified and echoed by the larger composition. Instead of creating a linear narrative, the grid creates a rhythm, one that honors the mundane. Unable to focus on the individual written items, we are unclear on the specific details of John Waters’s day. Instead we get an understanding of how he works.

Waters believes he was introduced to the index card in elementary school, through the library’s card catalogue. In the 1970s, Waters began his daily practice of writing a to-do list on a single 4×6 index card.1 When he completes a task, he crosses out the corresponding text on the card. Anything that is unresolved at the end of the day gets assimilated into the following day’s card. Once Waters procured an art studio, he began to accumulate the cards in a pile on his floor. After multiple permutations, Waters chose to organize the cards into a grid based solely on visual appeal. Once he is satisfied with the layout, he glues the cards to a board and photographs the final composition. The ensuing photographic print is titled based on the number of days–and cards–shown.

In the director’s commentary for one of his films, Waters mentioned that some Baltimoreans refer to his films as documentaries. Waters has used Baltimore’s eccentric characters as inspiration for and occasionally as the subjects of his films. These cards operate in a similar way. Though they function initially as tools to help Waters accomplish tasks throughout his day, once a card becomes outdated, it can only function thereafter as raw material. Each card becomes a unit that is both a record of a day and a drawing. It can now be combined with other units, which complement and embolden each other. Much like a film’s–even a documentary’s–raw footage, these modules can be assembled into whatever format achieves the desired aesthetic effect.

Interestingly, the information contained within each card is largely incomprehensible to the viewer. The writing is difficult to decipher, and when it is legible, it is often just a first name or a phone number. The lack of chronology removes context, as we are unable to make inferences based on nearby information. These obstacles create a tension for the viewer. Our brains want to interpret the text, but Waters has denied us the fulfillment of a linear narrative of his day. Instead he has given us an artificial one. Like his films, the subject matter may have roots in Waters’s real life, but this presentation evolves into something much more compelling than a clear delineation of his day. Rather, we are given a visual cacophony not unlike the work of the Abstract Expressionist painters whom Waters greatly admires. As in those mid-twentieth-century paintings, here too the form is the content–only instead of using paint mediated by emotion (or emotion mediated by paint?), John Waters expresses himself with file cards.

1. John Waters, in discussion with the author, 9 August 2011.

John Waters Biography