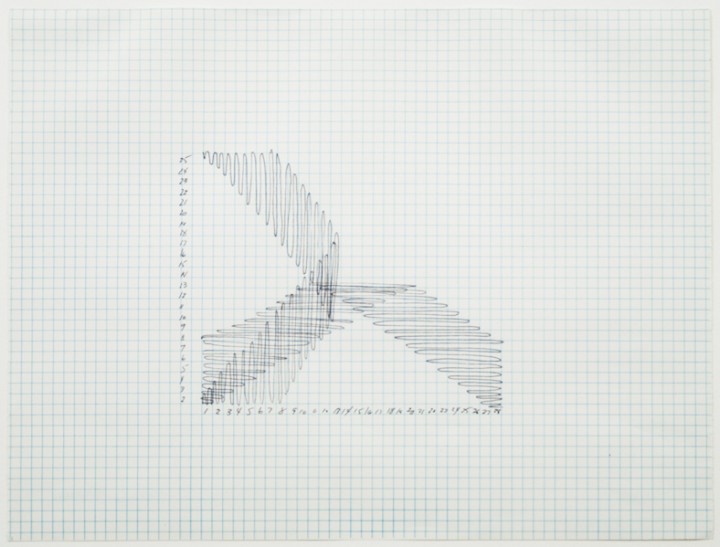

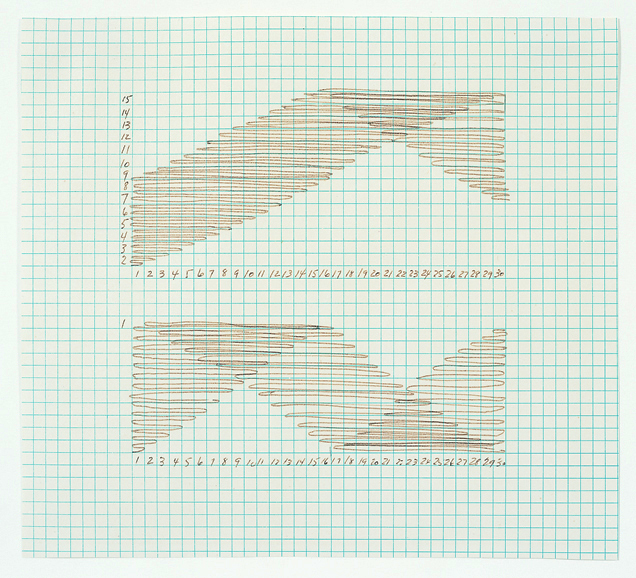

Trisha Brown’s works on paper Untitled and Drawing for Pyramid, both from 1975, are fluid while still systematic, seemingly spontaneous and yet also deliberate. Although drawn on graph paper, Brown’s lines do not follow the grid: they run through boxes, up and down columns, using the blue lattice as a guide, not a directive. Brown’s career as a visual artist has spanned decades, and she has amassed a diverse portfolio. Her drawings are intriguing on their own–some resemble hieroglyphics, primitive writing, or Abstract Expressionist canvases–but they begin to emote more deeply when considered alongside her choreography.

Yes, the artist is that Trisha Brown, of the Judson Dance Theater in the 1960s; of Walking on the Wall in 1971 at the Whitney Museum of Art; of Glacial Decoy in 1979, with sets designed by Robert Rauschenberg; and of You Can See Us, a duet danced with Mikhail Baryshnikov in 1996. Drawing, for Brown, is a form of mental exercise, a way of attaining the intense focus necessary to create or perform her works. These works on paper were meant to convey to her dancers a sense of the rise and fall of the dance, not to instruct them where to stand or how to hold their hands.

Just as her choreography runs in cycles, Brown also explores a certain characteristic for a time in her drawings, before moving organically to another idea. Her works on paper have evolved over the years paralleling her career as a dancer and choreographer. Once one knows about the other half of her creative accomplishments, drawings like these begin more apparently to define motion through time or to trace the position of a rotating dancer’s feet. The works on graph paper, however, are unique within Brown’s output, made during a phase that roughly corresponds with the development of her “Mathematic” choreography series from the early 1970s, which explores the accumulation, deaccumulation, and reaccumulation of gestures. Drawing for Pyramid refers specifically to the dance Pyramid, one of the pieces in the “Mathematic” series. It is tempting to try to identify exactly what this work could diagram. Similar works have been explained as picturing movement between groups of bodies.

It may seem confusing that an artist esteemed for her breakthrough choreography and for distinctive and unexpected dances would confine herself to a grid. Yet when one considers how Brown has described herself as an “art machine”1 and how she has seen her body as a “piece of machinery that was looking for a driver, a pilot,”2 the logic behind her choices may become clearer. One recalls Andy Warhol’s desire to become a machine as well, to create one piece repetitively, without change or augmentation.

When watching a performance of one of Brown’s “Accumulations,” in which gestures and movements build one at a time and then decrease again in sequence, one might expect to see a body striving to control its human failings, the mind concentrating on completing each step exactly as it had been completed one cycle, two cycles, five cycles before. But the movement is fluid, and the performer is indifferent to maintaining uniformity among the motions. This is as it should be, and the drawings correlate to the spirit in which Brown choreographed. It seems easy to find in these lines the cycle of the dance—each square delineating one step or one turn performed by a dancer—but it is important to try not to equate the two media. Instead one should follow the gentle roll of the drawing as it turns back on itself, creating the gentle wave one can also observe in the current of her dance.

1. Annette Grant, “Misha and Trisha, Talking Dance,” New York Times 8 August 1999.

2. Joyce Morgenroth, Speaking of Dance: twelve contemporary choreographers on their craft (New York: Routledge, 2004), 60.

Trisha Brown Biography