Since the 1960s, Sol LeWitt has used language as a vehicle to shift the conventional parameters of art. Descriptive and notational text appears in his drawings, in titles for his three-dimensional structures, and as instructions for others to execute his wall drawings. He wrote the highly influential treatises “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” (1967) and “Sentences on Conceptual Art” (1969), which proffer concise maxims about the new Conceptual art then emerging in galleries and art magazines. LeWitt’s diagrammatic drawings and hard-edge abstractions even elicit a distinct type of language from his viewers; in the presence of such work the traditional art-world vocabulary of shading, composition, emotion and skill becomes irrelevant and inadequate. The viewer is instead tasked with a novel experience of art, one that prioritizes the deciphering of a system over an aesthetic experience of a beautifully rendered object.1

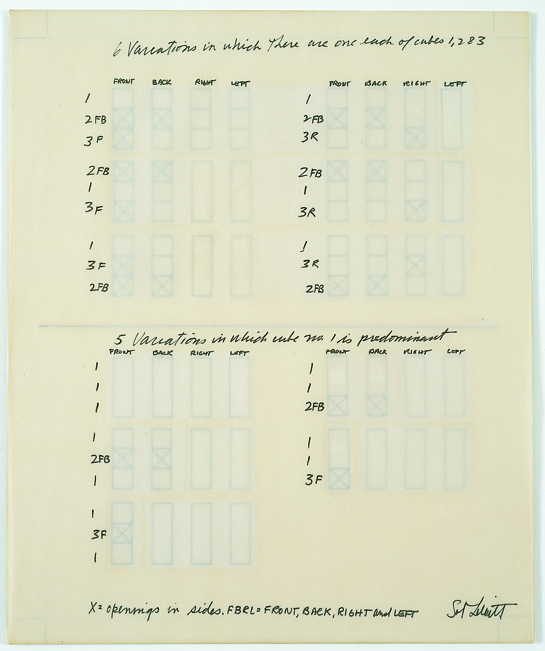

The two drawings included in this exhibition relate to the two fundamental forms LeWitt’s art has taken: modular cubic structures and wall drawings. In the earlier drawing, 6 Variations/ 1, 2, 3 (1967), LeWitt has plotted several permutations of the subject that preoccupied him for nearly a decade: the open cube. The artist explained, “The most interesting characteristic of the cube is that it is relatively uninteresting…the cube lacks any aggressive force, implies no motion, and is least emotive.”2 In the 1960s, by which time the art world had abandoned nearly all rules, the demand that a work be “interesting” seemed to be the only parameter left. LeWitt flirted with defying this tenet when he described the cube as uninteresting; however, he employed the inexpressive shape so as not to distract from the interesting idea at the core of his work. LeWitt explored the open cube in linear diagrams, axonometric drawings and three-dimensional constructions ranging from diminutive models to large-scale structures. These varied representations are often exhibited alongside one another as a means to address the different ways a singular subject may be rendered. The drawing 6 Variations relates to this large body of work, juxtaposing textual description, diagrammatic representation and the implied yet absent three-dimensional manifestation of these ideas. In 6 Variations, while the language is rudimentary and the overall concept simple (these are types of cubes), the viewer confronts the much more obtuse project of making sense of his system of Xs and imagining all variations possible in addition to those offered on the page.

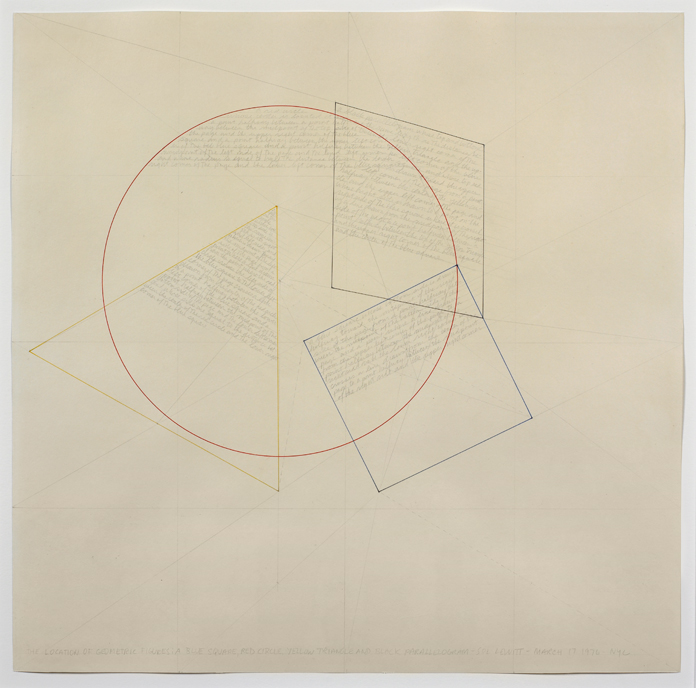

The relationship between simplicity and complexity is further explored in the later drawing, The Location of Geometric Figures: A Blue Square, Red Circle, Yellow Triangle, and Black Parallelogram (1976). While the free-floating shapes are precise and clear, in the vein of mechanical drawing or children’s educational tools, the text bound within them is circuitous and prolix. The handwritten sentence nestled into each shape describes the location of that shape and its relationship to the neighboring forms. LeWitt employed just such language as instructions for his wall drawings, geometric systems carried out by others according to his directions. The text is sometimes, but not always, written adjacent to the wall drawing; when the text appears, it underscores the original idea and the process utilized to carry it out. In The Location of Geometric Figures, written and drawn articulations of LeWitt’s idea are intimately mapped onto one another. They become redundant in this shared space on the page, provoking us to question the difference between textual and visual representations and their validity as artistic tools.

The period spanning these two drawings was a remarkably rich phase of LeWitt’s career, both in the quantity of works he produced and the quality of innovations he devised. LeWitt interrogated the relationship between the idea and its realization, between what is present and absent, between complexity and simplicity, and between different modes of representation. Language, as its own closed system riddled with these very tensions, operates at many levels of LeWitt’s work. As viewers, we are prompted to reconsider the role of language—both the words we see on the page and the ones we use to discuss art.

1. While LeWitt emphasized that his conceptual art is “made to engage the mind of the viewer rather than his eye,” many maintain that one cannot disregard aesthetics entirely. After all, it is nearly impossible to ignore the elegance of LeWitt’s softly stenciled geometric wall drawings. Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs of Conceptual Art,” Artforum 5, no. 10 (June 1967), 79-83.

2. Sol LeWitt, quoted in Sol LeWitt (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1978), 172.

Sol LeWitt Biography