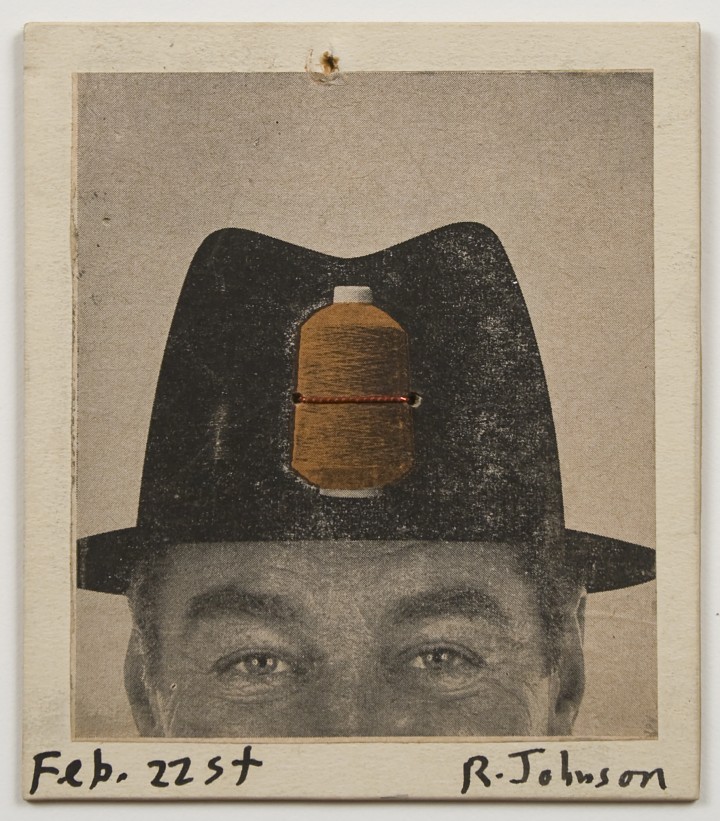

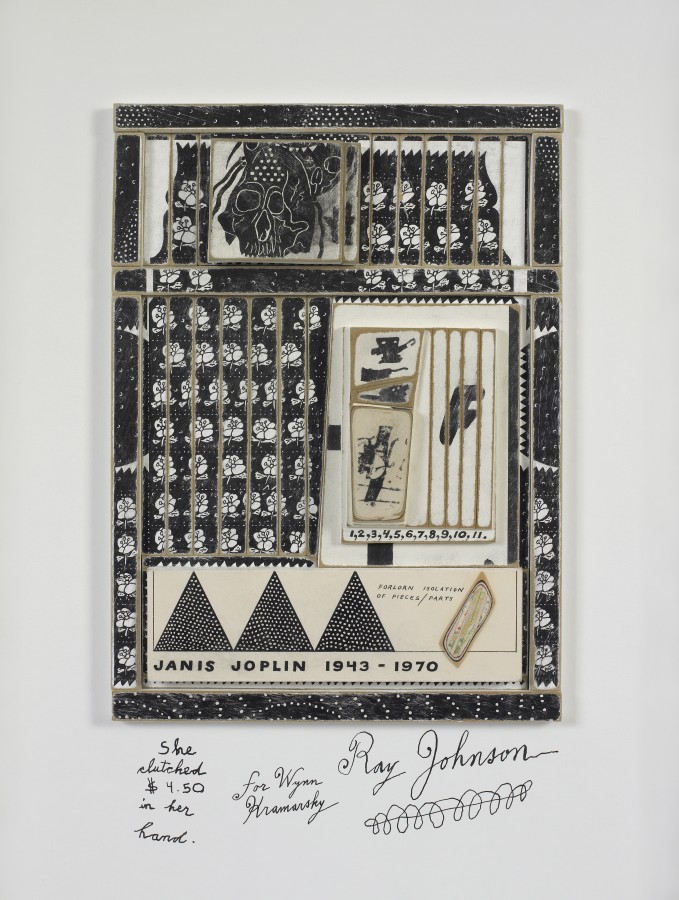

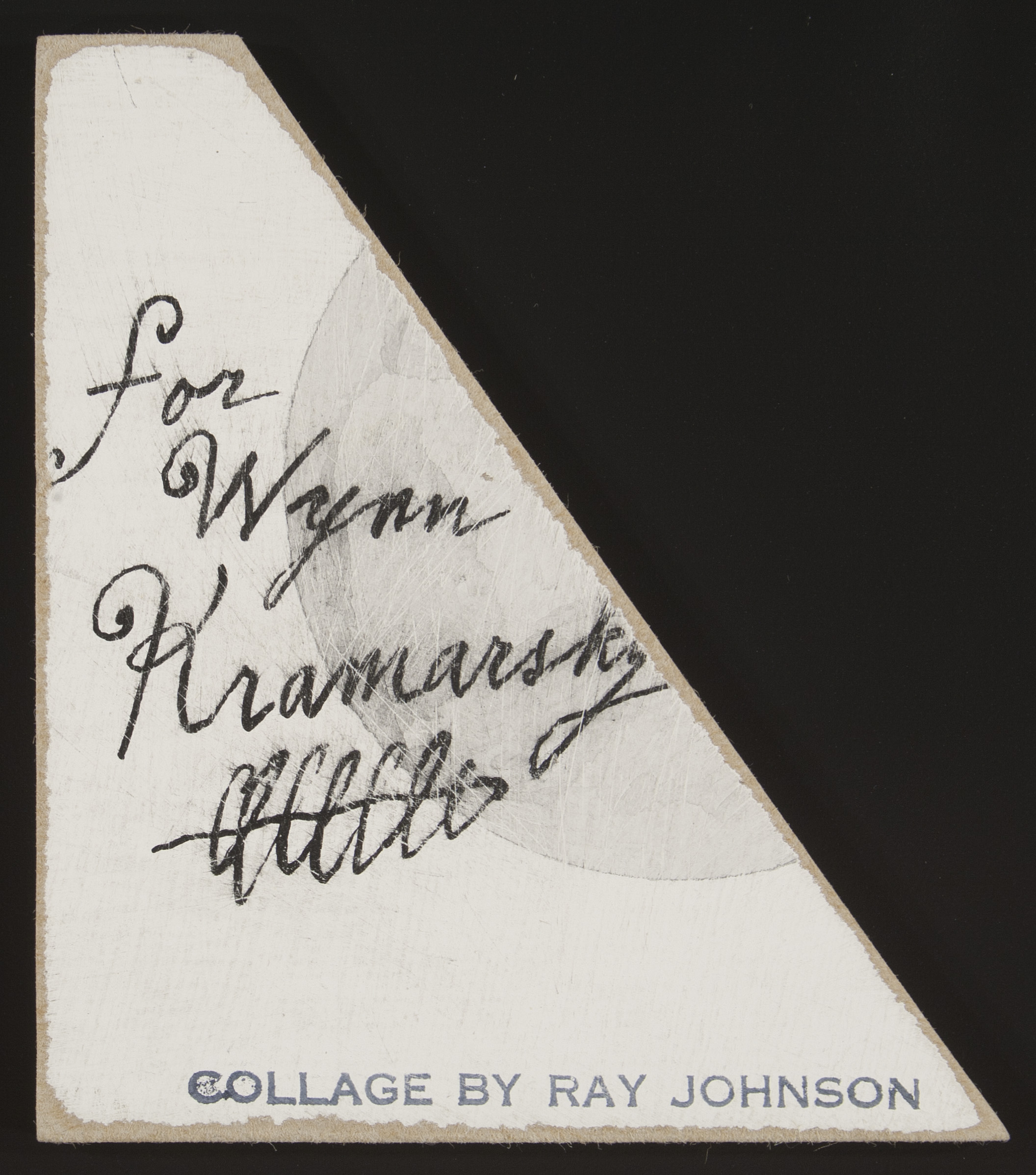

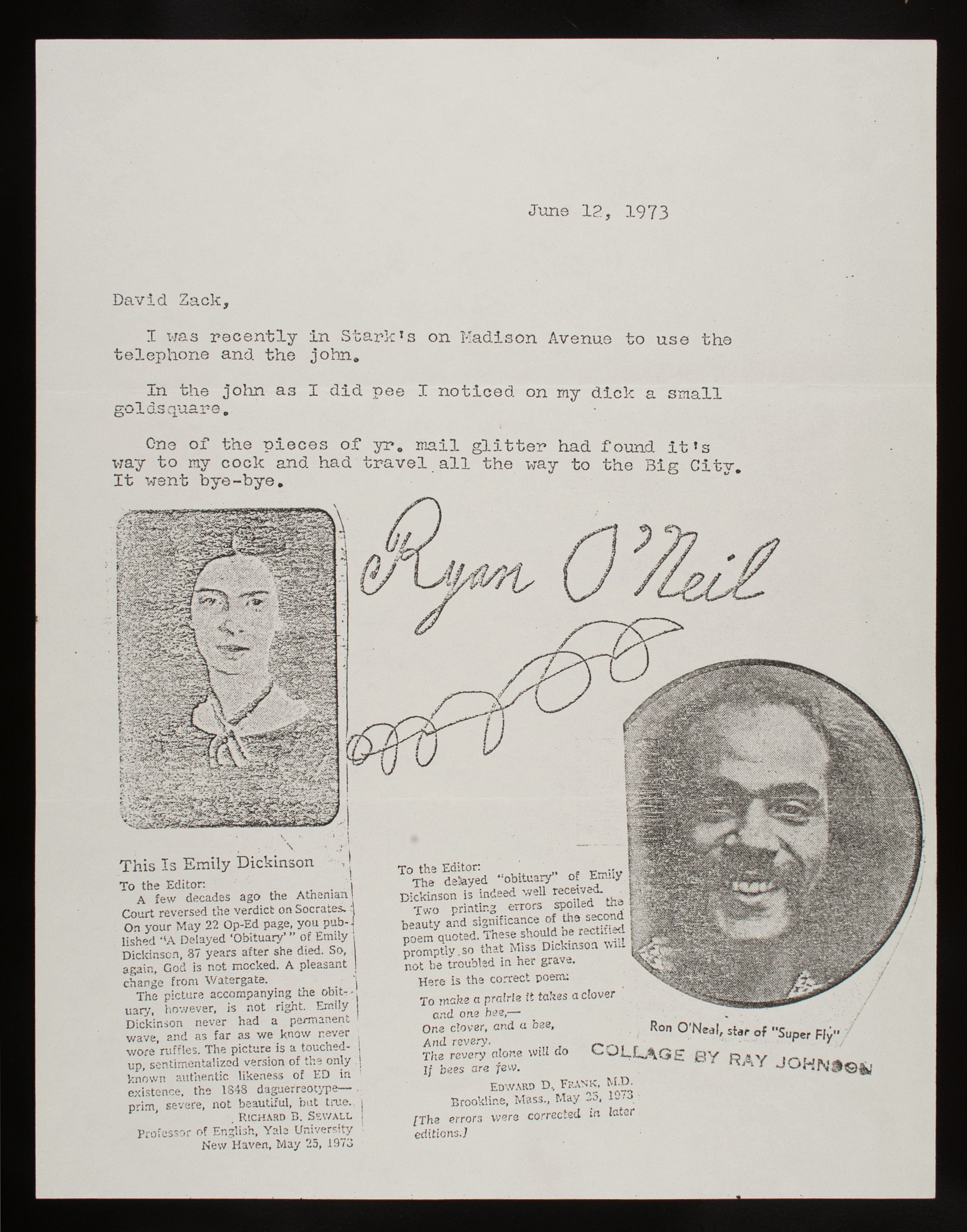

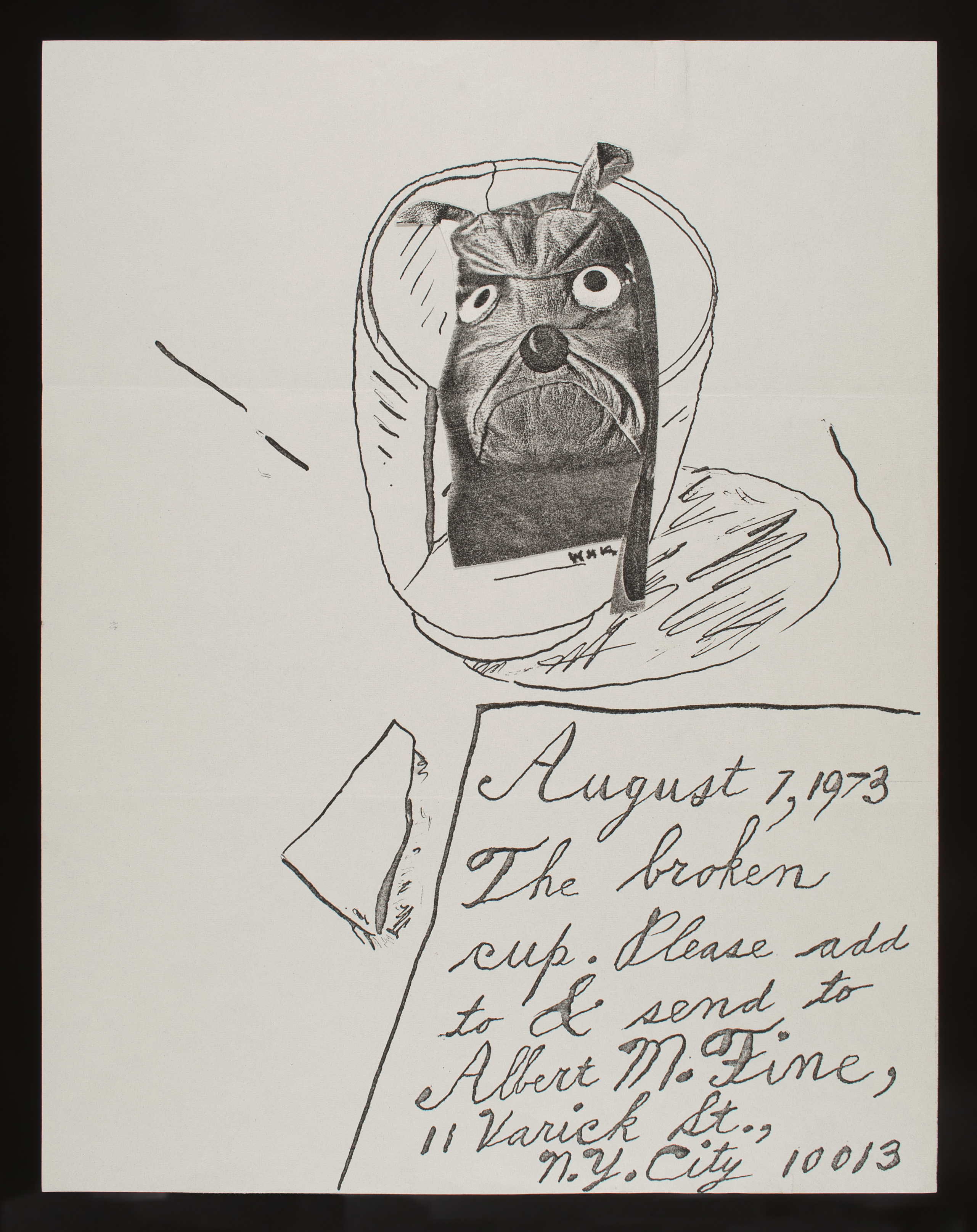

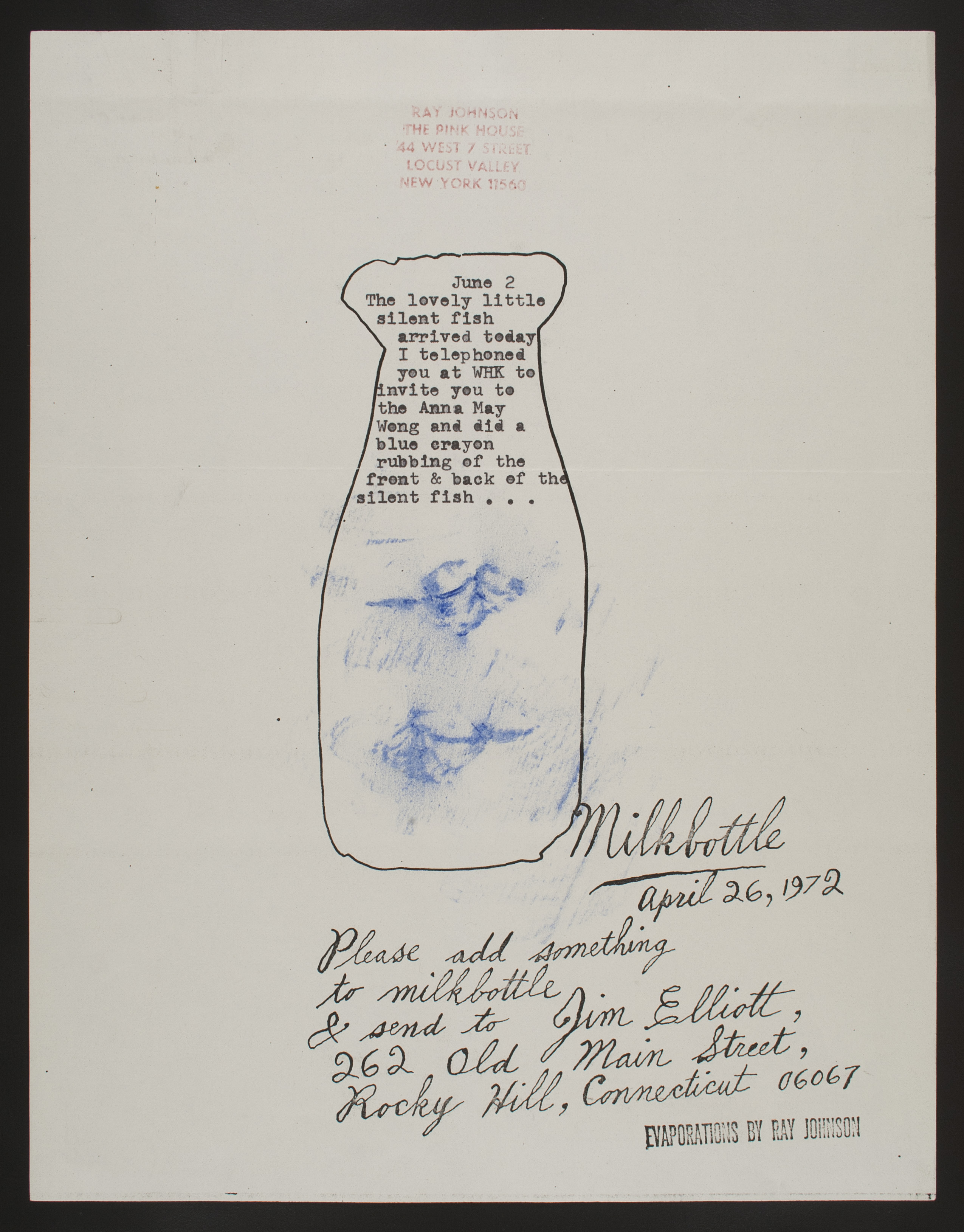

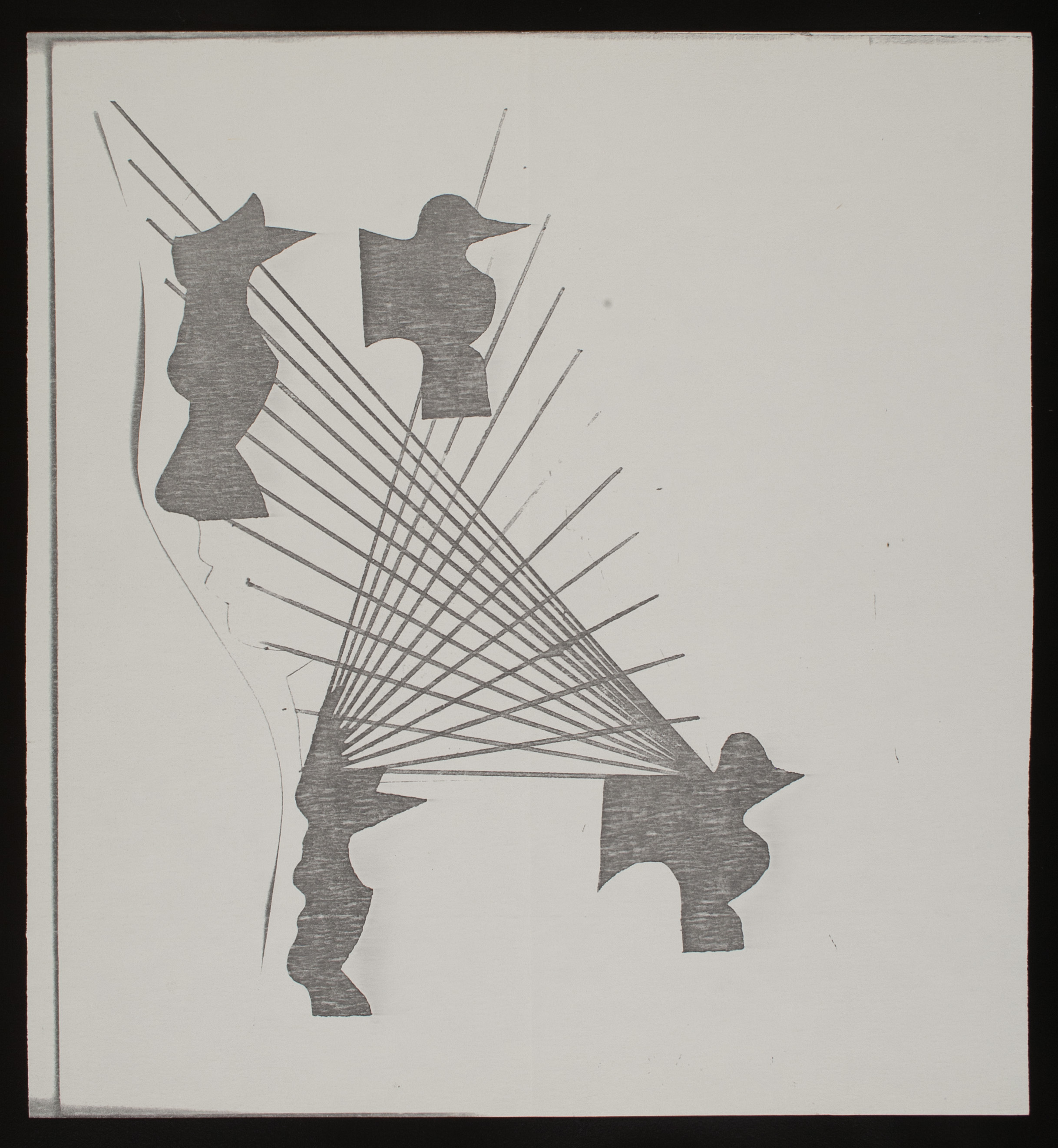

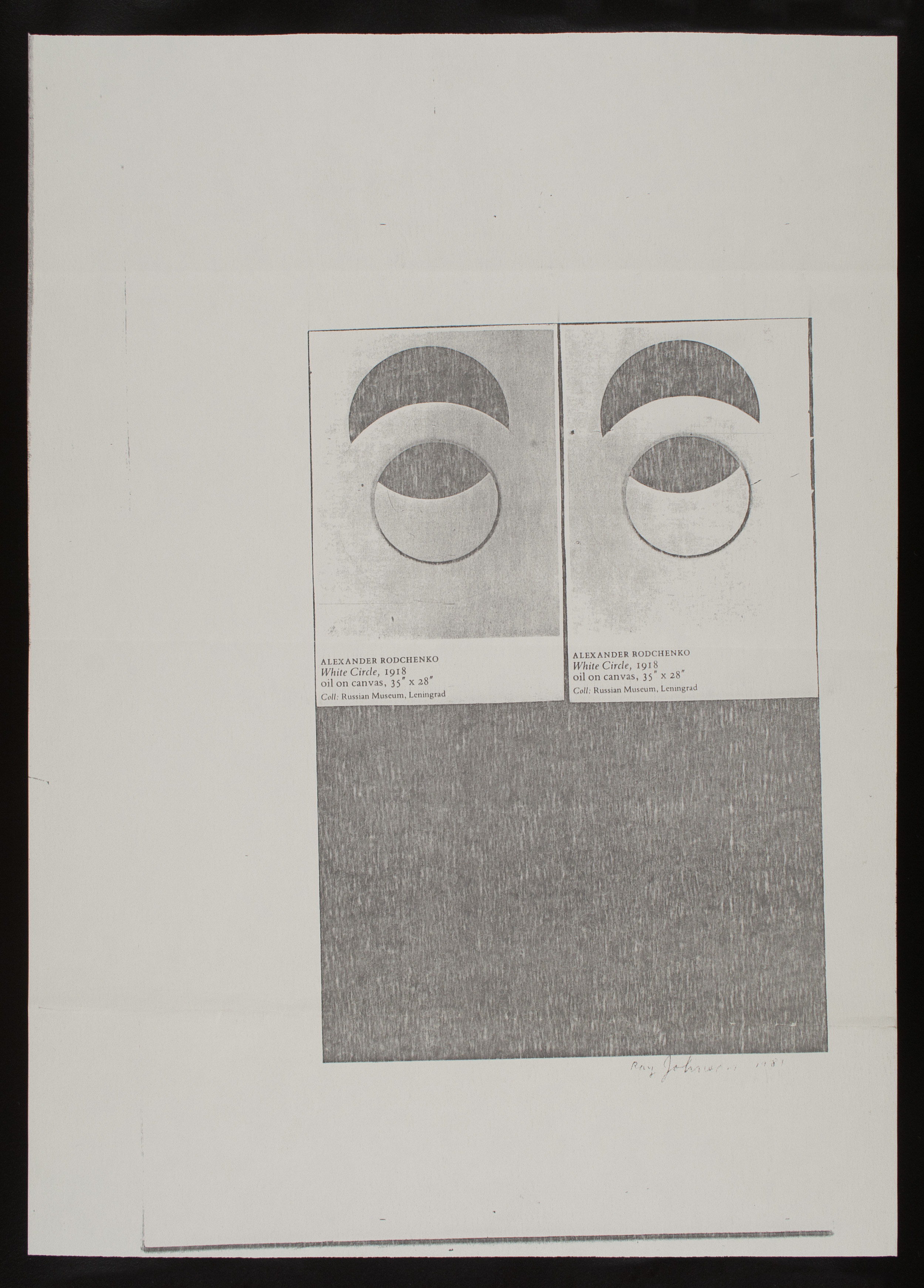

Ray Johnson, BOO[K], ca. 1955, artist’s book: collage on cardboard cover with hand-sewn binding; handwritten text and drawing in black and red inks on cut paper pages, 8 x 6 inches (20.3 x 15.2 cm), closed. © Ray Johnson Estate, Courtesy Richard L. Feigen & Co. / Photo: Ellen McDermott

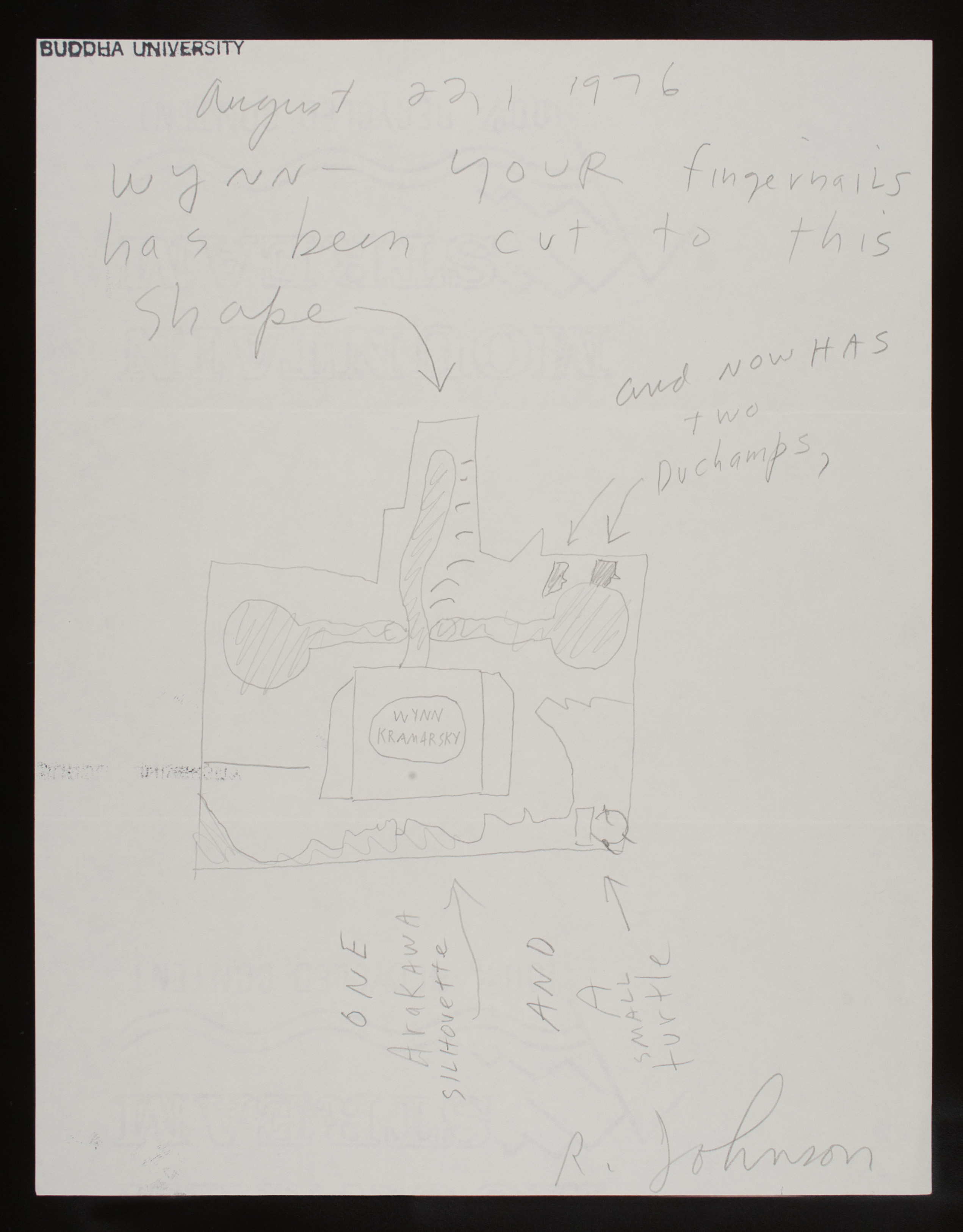

Ray Johnson’s BOO[K] (ca. 1955) exemplifies the intellectual investigation of many homosexual artists of the period—mobilizing words’ polysemic qualities to challenge and undermine dominant culture’s power to dictate meaning. An interest in the multiplicity of meanings is central to the work of Johnson’s fellow homosexual artists, such as Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Robert Indiana, Jess, and Cy Twombly, for whom, in the highly homophobic atmosphere of the Cold War, the prospect of authorial expression was fraught with danger. As such, they created highly developed strategies for mediating expressivity—self-conscious strategies, which in every instance called into question the very notion of the authorial.

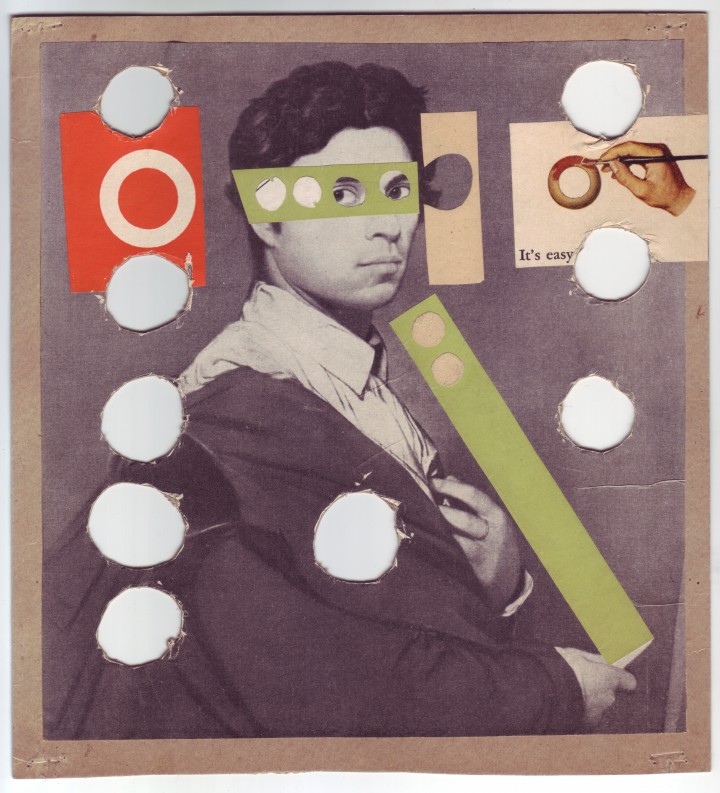

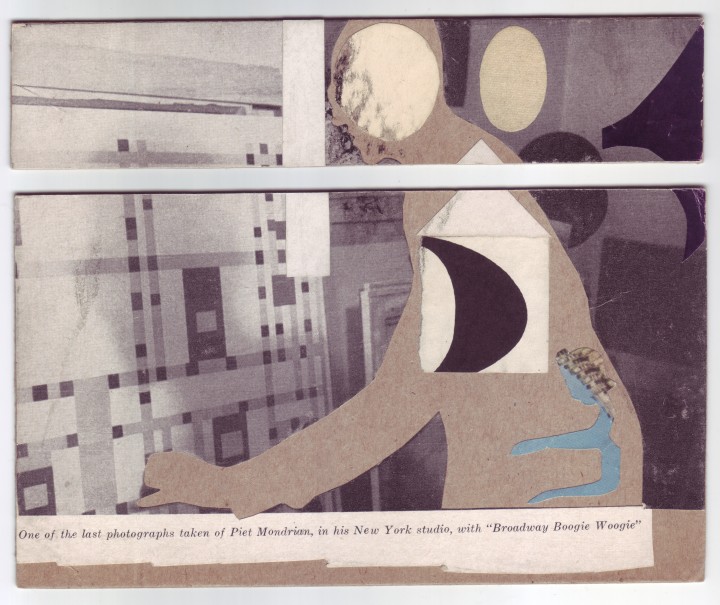

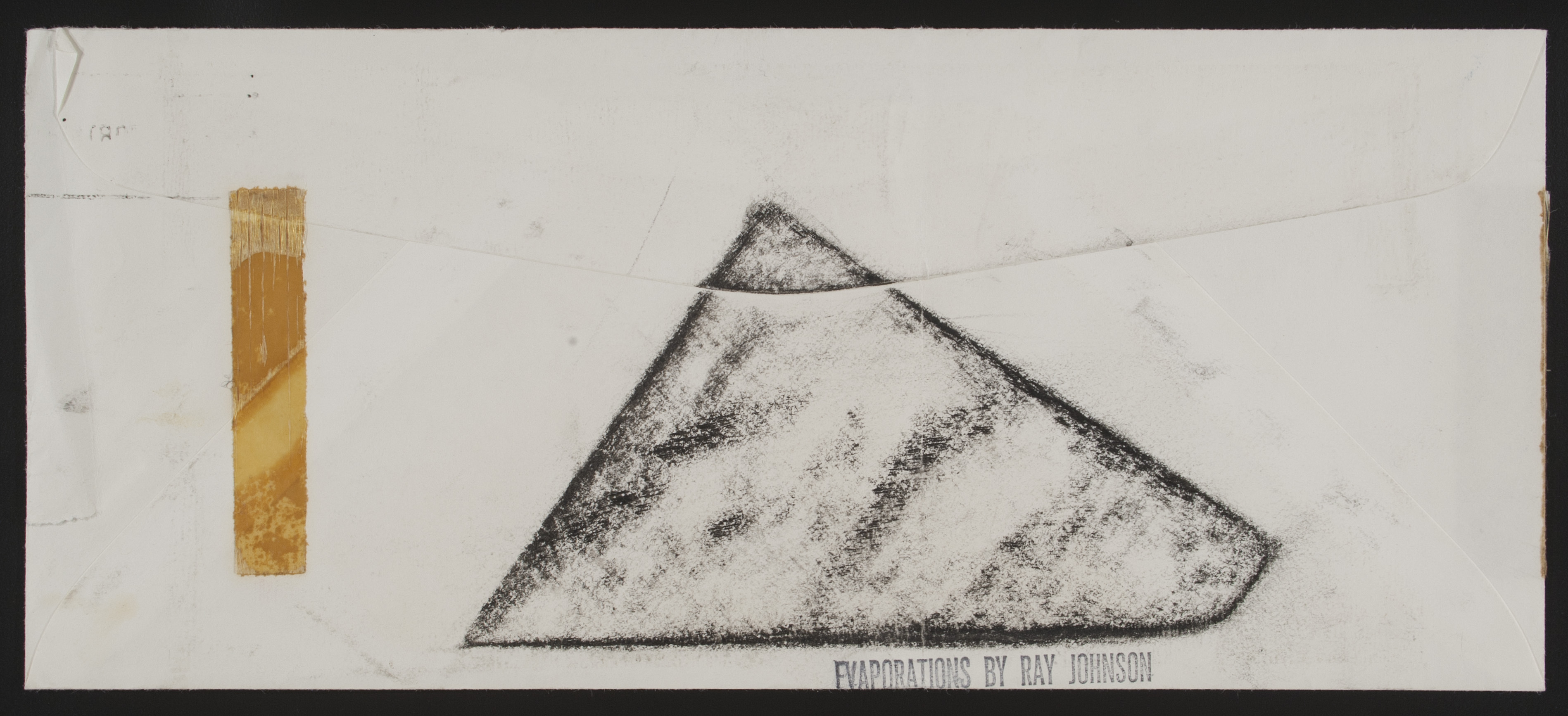

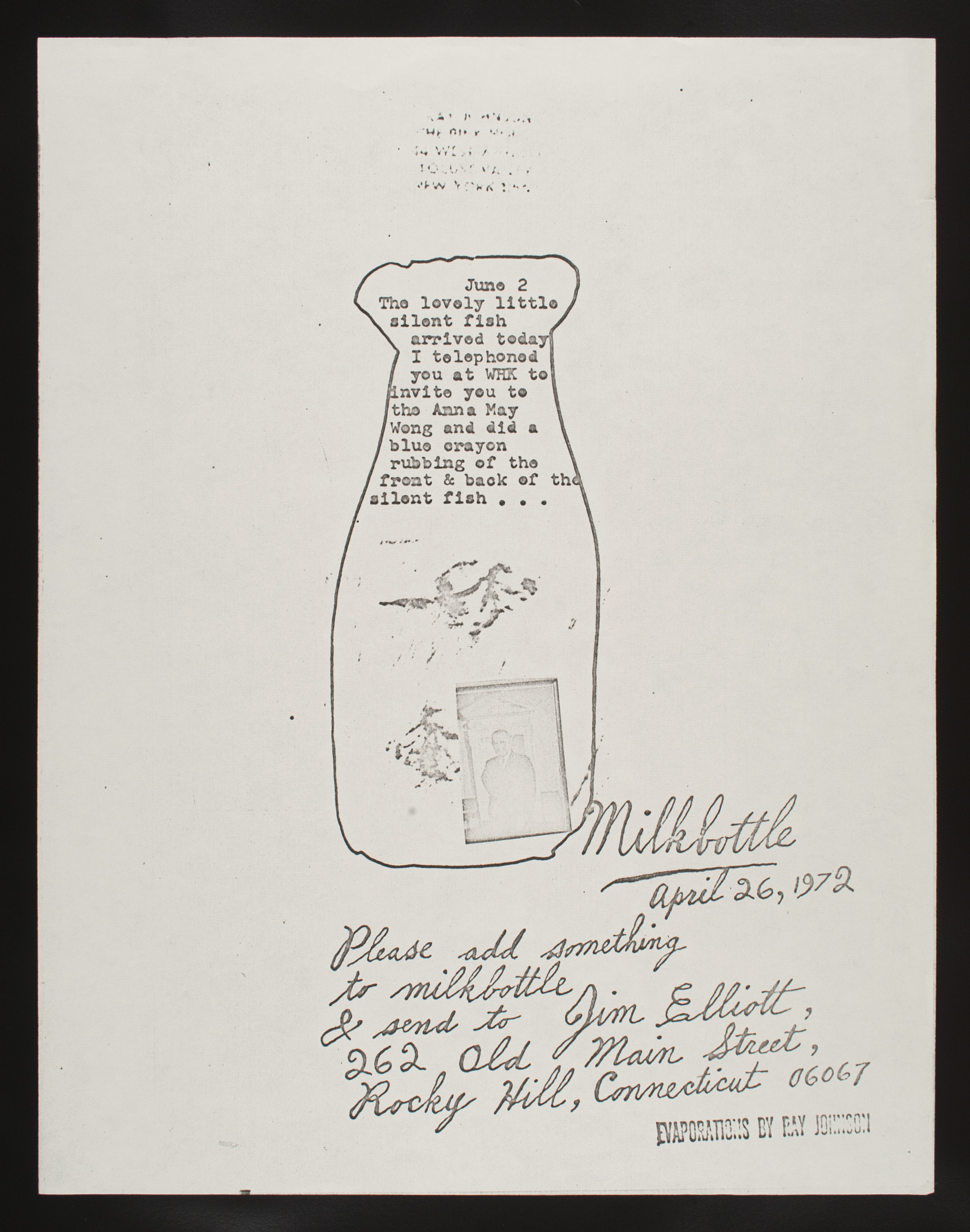

This hand-crafted artist’s book, consisting of cardboard-mounted collaged images and black and red inked letters on translucent cut paper. Johnson’s use of translucent paper allows words on underlying pages to show through both sides of the page, enabling readers to create their own readings; subverting the traditional notion that the author fixes the meaning and the reader merely receives it. In its ability to be read forward or backwards, and on multiple pages simultaneously, BOO[K] decenters the conventional linearity of reading. Alternate readings are always present, which one can either attend to or ignore.

Johnson called his collaged works moticos, an anagram of the word osmotic, which conveying ideas of permeability and transmission emphasizes the works’ fluid verbo-visual qualities. In BOO[K], Johnson employs the paper’s transparency to play with notions of primary and secondary content. For example, on the right-hand page, behind the words Mother has a picture book we can read the ghosted words from the following page: May I see and mother? We can interpret this phrase as a request to see mother’s book or as an inquiry about the presence of the mother. Through strategically placed cutouts, Johnson alternately obscures and reveals text, evoking a tension between hidden and visible meanings. On the right-hand page, a rectangular opening has been cut into the page such that the fragment boo, in red ink, is revealed from the underlying page, while the k, in black ink, is present on the topmost page. In dividing the word in this fashion, Johnson ironically echoes these artists’ lived experience: bifurcated and differently legible according to one’s point of view.

The use of language as a tool of power was viscerally palpable to Cold War-era homosexuals, for whom this identificatory label was not merely descriptive, but a scarlet letter used to police and persecute them. Certain terms, such as heterosexual, became coterminous with normalcy and others, such as homosexual, coterminous with deviance. Revealing the dynamics of the process by which these ideological mystifications took place was a central problematic for these artists. In making clear that words mean differently in different contexts, they sought ways to demonstrate that all such labels – and the qualities they name – are mythologized as natural and enduring, rather than being recognized as the shifting and arbitrary product of social construction. As Slavoj Žižek explains, “one of the fundamental stratagems of ideology is the reference to some self-evidence – ‘Look, you can see for yourself how things are!’ ‘Let the facts speak for themselves’ is perhaps the arch-statement of ideology – the point being, precisely, that facts never ‘speak for themselves’ but are always made to speak by a network of discursive devices.”1

BOO[K]’s physical qualities literalize these artists’ interests by showing how language itself is never fixed but instead a layering of meanings upon which the reader draws. BOO[K] is literally read through its pages, making visible the way in which a text always draws upon references that are external to it, becoming, as Roland Barthes claimed, a “tissue of citations.” By highlighting each individual’s agency in meaning-making, BOO[K] facilitates the reader’s recognition that vision is neither passive nor purely receptive—that what you see depends on where you sit. For homosexual artists in the Cold War consensus culture, this possibility was key toward their larger goal of destructuring a homophobic culture organized around a very particular angle of vision concerning the “natural.”

1. Slavoj Žižek, “The Spectre of Ideology” in Mapping Ideology, ed. Slavoj Žižek and Nicholas Abercrombie (London, Brooklyn: Verso, 2012), 11.

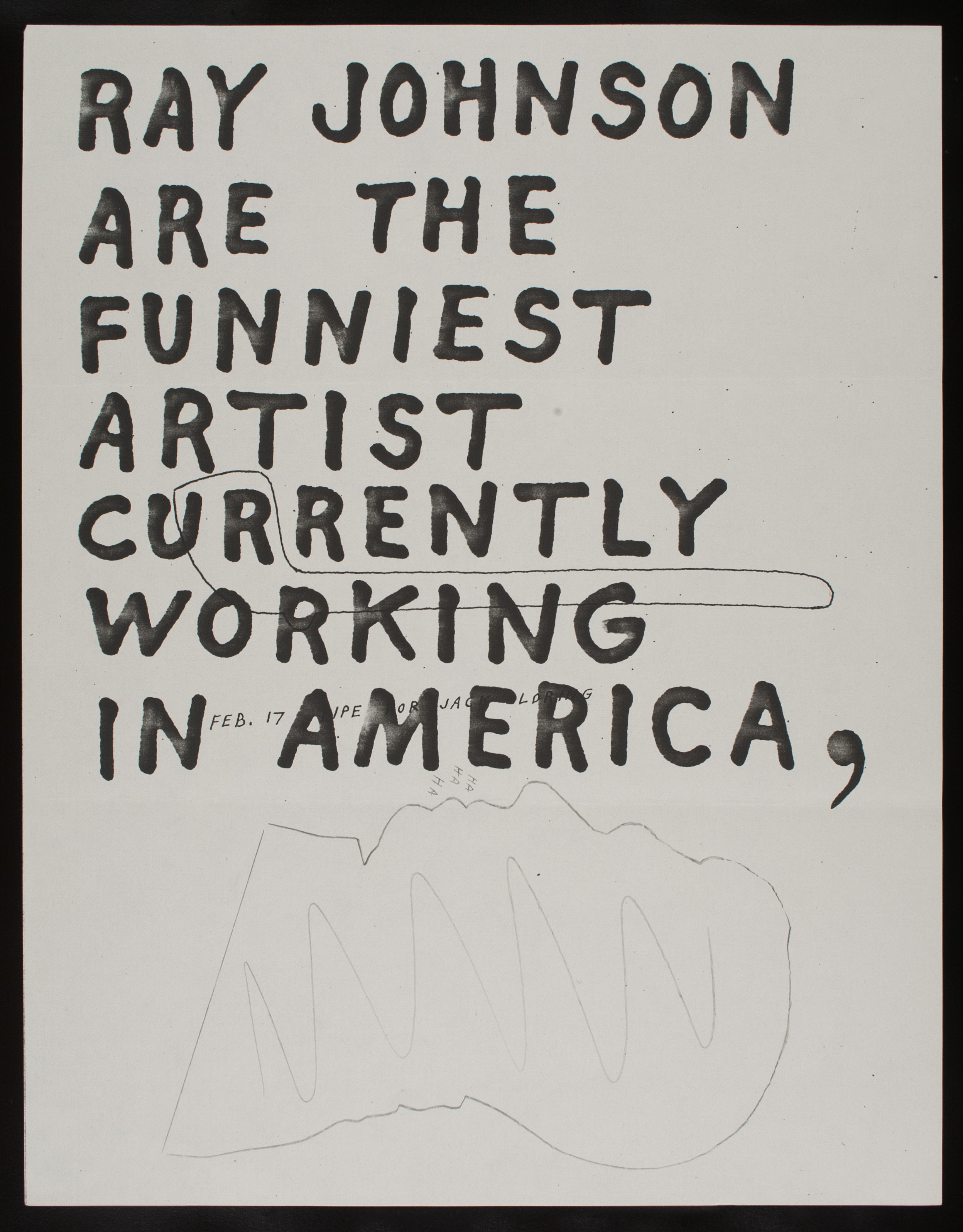

Ray Johnson Biography