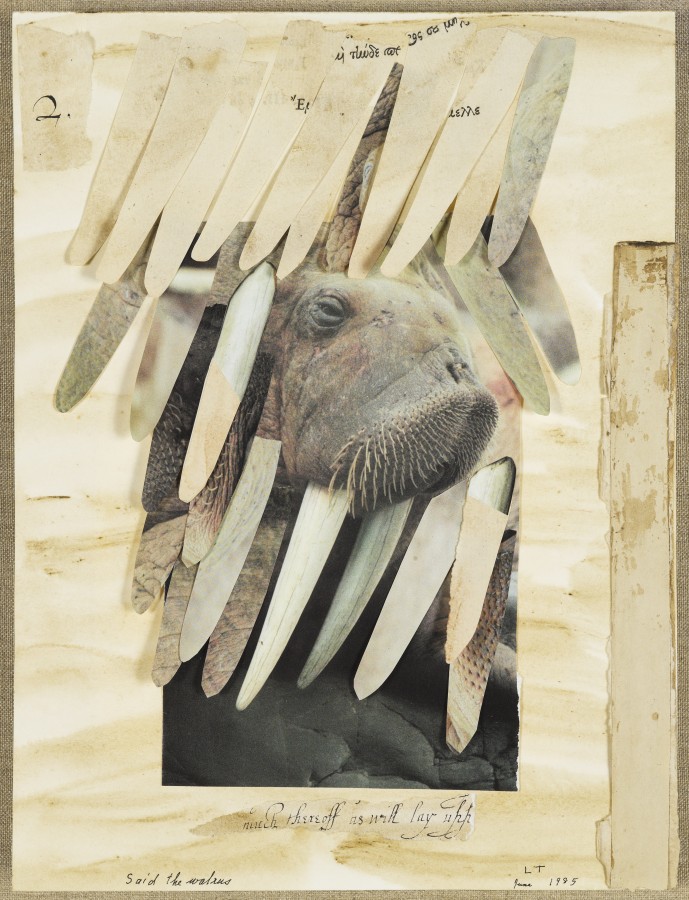

Said the Walrus to the Carpenter, It Would Be Very Nice (1985), a collage by Lenore Tawney, features an image of a walrus that protrudes through a curtain of oblong shapes. One of Tawney’s later collages, Said the Walrus is a reference in both title and subject to “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” a narrative poem from Lewis Carroll’s 1871 book Through The Looking Glass, which explores the theme of deception through meaning in language. In the poem, the Walrus uses word play to trick a spat of oysters into attending a feast at which they all are eaten. The Walrus in Carroll’s poem is complacent in carrying out his deceit, but he expresses reservation about the trickery in which he engages. By exposing the implications of the plot afoot, the Walrus becomes the mediator between the audience and the events in the story.

The image of a walrus in Tawney’s piece is framed by a cut-out square, which, in concert with the shapes collaged over the top, suggests a stage. Tawney’s contextualization of this image in a stage-like frame introduces an element of performance, a form of play between language and action. Play is associated with the mobility of meaning – the combination of two elements that are not usually put together – which presents a challenge to fixed meaning. Alternative meanings enable the possibility of difference, and the Walrus in this work is the character that exposes an alternative to the story: letting the oysters go, rather than perpetuating the trap.

Challenges to authoritative meaning are common throughout Tawney’s work, and she often looked to artists around her for material, taking the formal strategies of others and processing them through her own personal referential vocabulary. A striking element of Tawney’s work is its almost diametric opposition, in its personal inflections, to that of her once-partner, Agnes Martin.1 One of the foremost figures in geometric abstraction in the post-war period, Martin’s artworks offer little in the way of external or personal referents beyond her meticulously handcrafted grids. Tawney’s Biblioteca Chemica (1966) consists of a wooden rack of square compartments filled with small vials of material. This work echoes Martin’s formal vocabulary, but in lieu of carefully rendered lines, Tawney employs a found object as the grid formation. The small vials, labeled by hand in tiny script, contained within infuse the work with a sense of the personal; we can read the artist’s handwriting on the tops of the rubber stoppers. By deploying handwriting and hand-collected materials alongside the grid—which is associated with uniformity and yet, somewhat paradoxically, is also the signature formal strategy of her once-partner—Tawney performs a complex conflation of the personal and the impersonal. Thus she makes the mechanisms that bridge or challenge distinctions between public and private meaning the subject of her work.

1. There is no evidence in the Lenore G. Tawney Foundation archives of the relationship between Lenore Tawney and Agnes Martin. However, given the social strictures of the time, such an omission is hardly surprising. Several other sources in the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art nonetheless address their relationship. For further information, please consult Jonathan D. Katz, “Agnes Martin and the Sexuality of Abstraction,” in Agnes Martin, eds. Lynne Cooke and Karen Kelly (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 92-121.

Lenore Tawney Biography