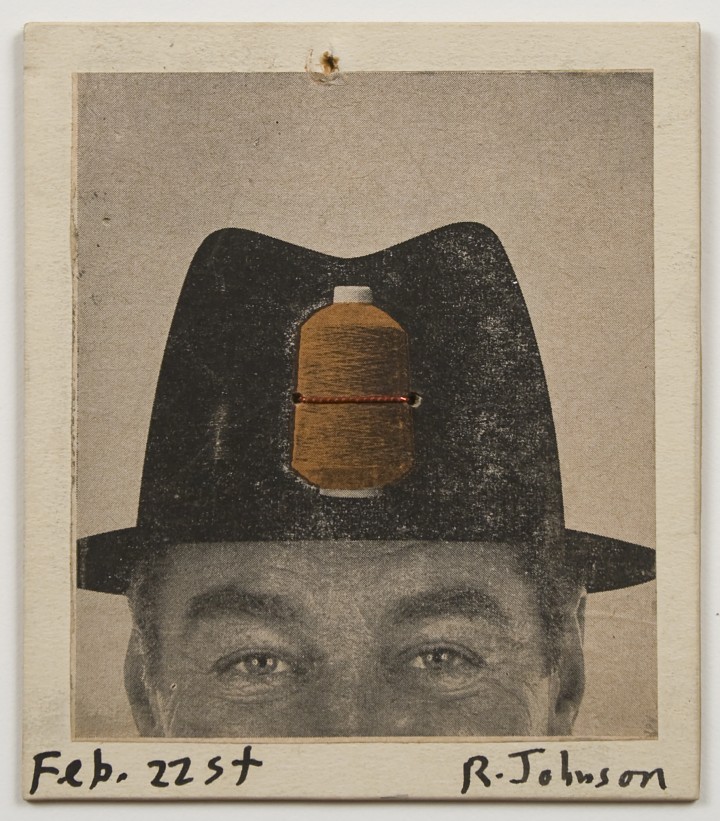

Best known for his work in collage and correspondence art, Ray Johnson remains an enigmatic figure in the post-war American landscape. His use of time- and community-based media—such as objects sent through the US Postal Service—added a dimension to his work that differentiated him from his cohort. Correspondence art resonated primarily with the practices of a slightly older generation of artists, including John Cage, whose work followed principles of conversation rather than communication, the former implying egalitarian involvement and the latter more closely associated with dictation. Ever curious about meaning, Johnson often turned to puns and homonyms as a way of introducing multiple simultaneous meanings into a picture. In Untitled (Man In Hat) from 1960, Johnson uses a found image of a man wearing a hat, onto which is superimposed a spool of thread. Though the spool looks like a collage element, it is in fact native to the printed image; Johnson has added only the thread, which appears to be wound around the spool in the picture. This is a classically Johnsonian conceit: a visual play between what is appropriated and what is inserted, and also a linguistic rhyme (head/thread).

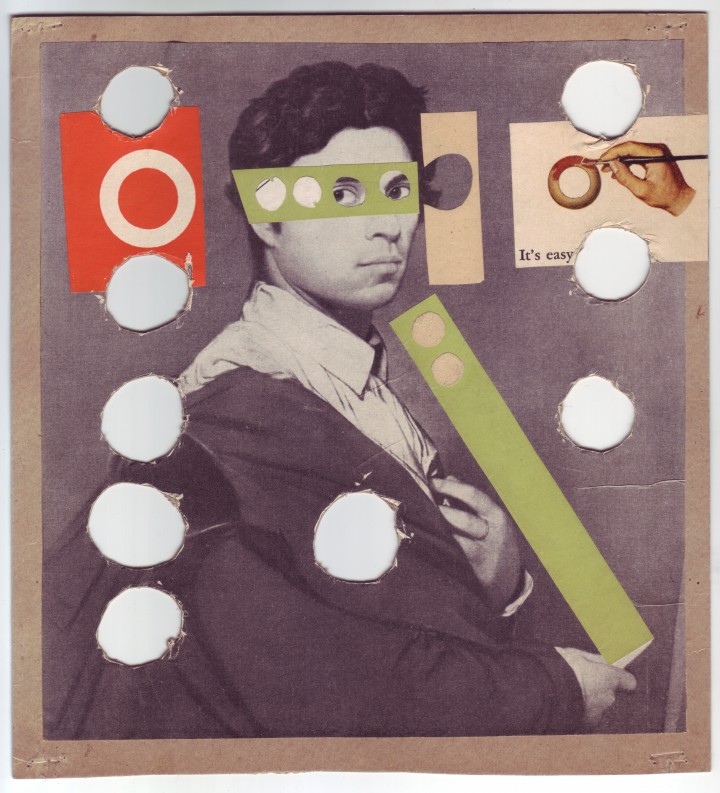

Two later collages in the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, suggest Johnson’s exploratory engagement with the historical evolution of meaning in fine art. Both pieces, undated but likely made in the 1970s, use images cut from art catalogues of the time. One of these collages features a reproduction of an 1804 self-portrait by French Neoclassical painter Jean-August-Dominique Ingres, excised from a magazine and mounted on cardboard. Circular holes have been cut out of the picture and cardboard, echoed by similar holes cut into the strips of paper collaged over various parts of the composition. A collage element affixed toward the right edge, also cut from a magazine, bears a picture of a hand painting a circular shape red, with the words, It’s easy, printed below.

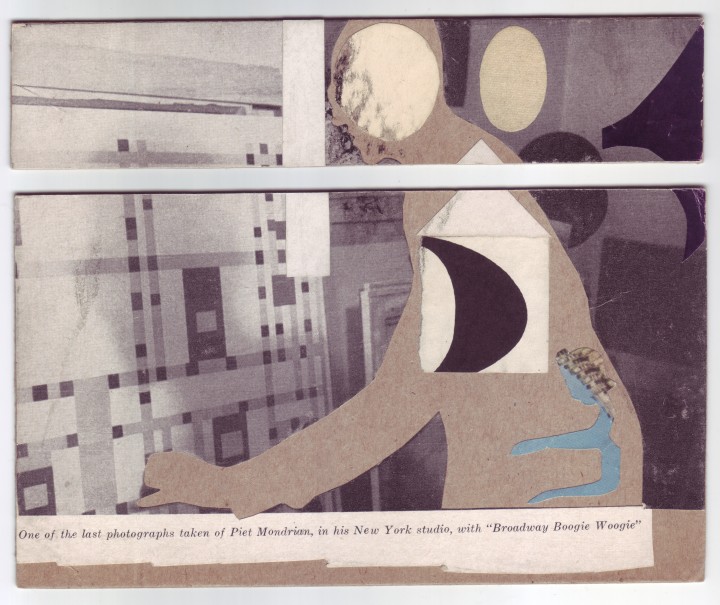

Ingres, one of the early forebears of Modernism, is renowned for his renderings of complex spatial relationships, which served as examples for later generations of artists, including Piet Mondrian, whose work Johnson repeatedly referenced. Indeed, the other collage on view here features a photograph of Mondrian in front of Broadway Boogie Woogie, arguably his most famous late painting. Johnson has cut Mondrian’s body out of the picture, leaving only the artist’s outline to suggest his presence. By making Mondrian conspicuously absent and by partially covering Ingres’s face, Johnson puts particular pressure not just on the relationship of artist to artwork, but also on the authorial presence and visibility of the artist within a finished work of art. If we can understand the inclusion of Ingres as Johnson’s protest against dismissal of artworks on the basis of form without consideration of conceptual depth, the physical absence of Mondrian can in turn be understood as Johnson’s investigation of the presence of the artist – or lack thereof – and its effect on the terms of reception for a particular work or idea.

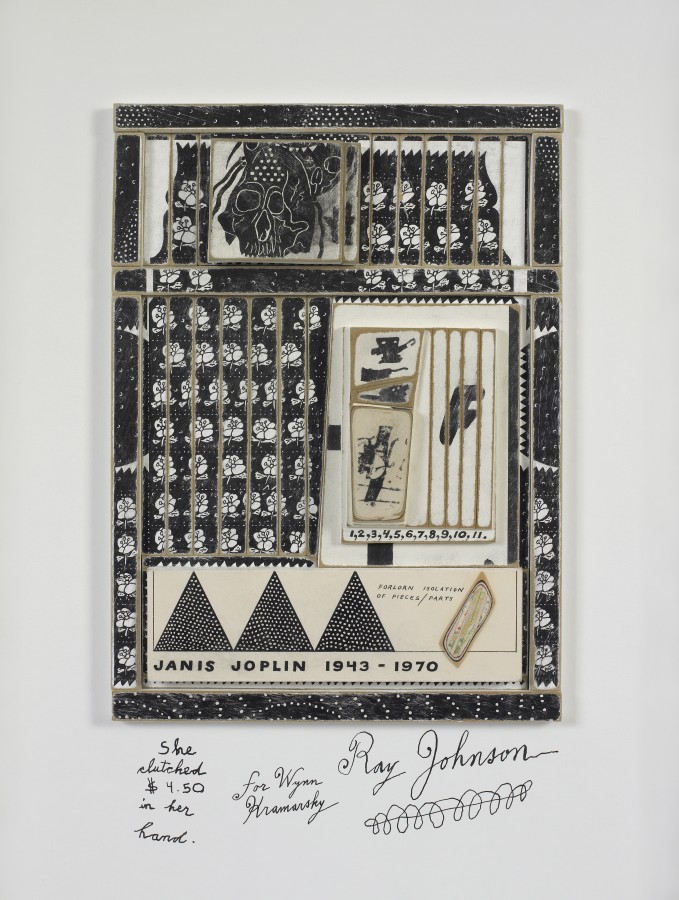

Johnson’s primary medium was collage, but unlike in the objects discussed above, the majority of his collages comprise a cut-and-pasted combination of found images and the artist’s own repetitive drawings—of snakes, for instance, or of bunnies. By excising images and words from their usual contexts and re-inserting them in other, less frequently used spaces, Johnson coaxes these fragments to assume various new meanings – a practice that opened the door to alternative interpretations. This working method became central to Johnson, Rauschenberg, and other post-war artists. In Janis Joplin (1971), Johnson uses the theme of Joplin’s death that same year as a referent, but the effect of the resulting “portrait” transcends both Joplin and death. It is Johnson’s presence—made known through the hand-drawn moticos and sequences of numbers and shapes—that seems to dominate, not that of his ostensible subject. Johnson is his moticos: we know him by these visual signs, rather than by his biography. The use of imagery linked primarily to Johnson in a work about Joplin in effect collapses the two. What Johnson calls to mind, here and elsewhere in his work, is the way a subject is constituted not by some essential fact, but by its relationship to other subjects. In foregrounding this paradox, Johnson enables the possibility of new and different thinking around identity and its networks.

Ray Johnson Biography