The Pleasure of the Empty Page

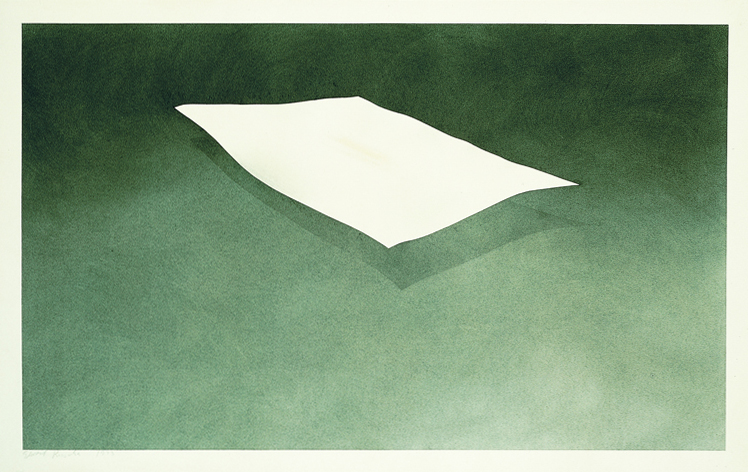

For any artist or writer, a blank piece of paper offers the possibility of expression, which is part of the reason it can be terrifying. The drawing Suspended Sheet Stained with Ivy (1973) by Ed Ruscha allows us to reflect not just on art as text, but on art as the absence of text, which has the potential to strike fear into any artist.

During the time when he was making this drawing, Ruscha was experimenting with new pigment materials, so he used gunpowder and crushed a common ivy plant to create a stain for this work. This process demonstrates an attempt to change methods of production, and perhaps also to see things anew. In discarding his usual tools, pen and ink or brush and paint, Ruscha forced himself to regain a sense of play. The drawing also evokes a return to the origin of art itself–the first impulse to create which caused ancient people to invent basic methods of production. In the cave paintings at Lascaux, for example, pigments formed from minerals allowed early humans to record their world. In the present, we often use materials made in factories–fine papers, special paints–but Ruscha, in a rare act of primitivism, decided to go back to the natural sources of those materials, in order to create his art in an unfamiliar way.

It’s compelling that his subject here is the blank page, since it is at the center of the artist’s practice. There’s something witty about drawing the image of a piece of paper on a piece of paper, but it’s the kind of wit that exposes an anxiety about the artist’s potential to create. The term horror vacui means “fear of an empty space,” and it’s a familiar feeling both to painters and to writers. (This feeling has been blamed for a proliferation of imagery and for an obsessively decorative approach to the visual arts.) The tabula rasa or “blank slate” of a clean piece of paper can be paralyzing to an artist who is searching for something to communicate. As a poetry teacher, I often hear the question, “What can I do about writer’s block?” Almost anyone who’s ever wanted to write has faced a blank page–or the blinking cursor on a computer screen–with the feeling that nothing he or she could write would be worthy of being written. The great French writer Colette thought her father had written a dozen books with exotic titles–My Campaigns, Elegant Algebra, Zoave Songs–which he kept on a shelf in his office. After his death, she opened them, and except for a dedication to her mother, every page was completely blank.

The poet William Stafford, in correspondence with Ursula K. Leguin, a poet and science fiction writer, said something along the lines of: There’s no such thing as writer’s block. Lower your standards. On a practical level, this is good advice. It soothes the fear of having to make work that matters, and it allows the work to regain its proper shape and size. But for a blocked writer, that empty page can seem like a monolith, and instead of a clean slate to be filled, it can seem like an impermeable barrier between the self and the writing that one wishes to do.

Ruscha’s drawing, however, lightens this subject–literally. His piece of paper is floating in air, weightless, defying gravity’s pull not for a moment, but indefinitely. It’s an illusion made real, and it’s delightful because it allows us to share his act of imagination. The piece of paper, which can seem so heavy if you don’t know what to do with it, is weightless in this depiction. Ruscha, in the process of liberating himself from traditional methods of drawing, allows us to see that approaching the means of art making with curiosity can infuse a certain levity into our existence. Without the baggage of our writing, our experiences, our depictions and imitations, this piece of paper defies all the false weight with which we’ve invested it. It floats, and we wonder at its potential. Fear is replaced by new feelings–disorientation, maybe, but also a sense of awe, or even a sense of the humor in our own intimidation by a simple piece of paper.

One of my hopes for this exhibition is that it will help people to apprehend their own relationships to art and text. So often we think of art as something outside of ourselves, practiced by “real artists” or “real writers,” usually people whose work has been bought and paid for by others. A gallery show or a publication, we think, is the mark of a “real” creator, and how are we supposed to match that? But art making and writing are as approachable and immediate as any piece of paper in front of you. If a child draws a picture, it’s no less an act of art making than the Ruscha piece you’re currently viewing. Anyone can do it, if he or she chooses to, and the practice of writing, painting, drawing, sculpting, or photographing is a life-long pleasure. It allows you to express the things that are truly unique about you: your perspective, your experience, your understanding of the world. When you leave the museum today, challenge yourself. Pick up a piece of paper–not a computer or a cell phone. Return to the ancient process of writing or drawing the first thing that comes to mind. Give yourself permission to care about it, and equal permission to give it away. You’ll be surprised at what you’re capable of creating, if you give yourself the chance.

And if you have trouble? Lower your standards.

Ed Ruscha Biography

Susan Miller Biography