by Sarah JM Kolberg

Although text has long been used as a formal element in art, a radical shift in the 1950s catalyzed a new understanding of the relationship between words and images. This new mode made words themselves the subject of inquiry, putting them under pressure to reveal multiple meanings, and enabling them to create a space in which it is possible to recognize alternative interpretations. This subtle form of resistance did not directly oppose dominant culture’s control, but rather sought to neutralize its normalizing power, and irony became one of its principle weapons. Operating in the gap between what is said and what is meant, irony creates an opportunity for the reader to interpret a meaning quite different from the one implied by the writer. Most significantly, one interpretation does not cancel out the other, but rather both are equally viable. This new engagement with text in post-war American art put both words and images in service of opening that gap.

As we argue in this exhibition, it is no coincidence that the leaders of these innovations were homosexual. In the consensus culture of the Cold War, homosexuals were as vigorously policed as suspected Communists, with equally dire consequences. The prevailing understanding of homosexuality at this time didn’t include notions of love, only of deviance. Words such as love, so innocent in a heterosexual framework, became tainted with political threat when employed in a homosexual context. It is little surprise that gay artists were the vanguard of an art-making practice that was simultaneously resistant to dominant culture’s impositions of power and illegible as such.

![Ray Johnson, BOO[K], ca. 1955, artist’s book: collage on cardboard cover with hand-sewn binding; handwritten text and drawing in black and red inks on cut paper pages, 8 x 6 inches (20.3 x 15.2 cm), closed. © Ray Johnson Estate, Courtesy Richard L. Feigen & Co. / Photo: Ellen McDermott](http://artequalstext.aboutdrawing.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/3452_Web-697x900.jpg)

Johnson’s use of translucent paper allows words on underlying pages to show through both sides of the page, enabling readers to create their own readings; subverting the traditional notion that the author fixes the meaning and the reader merely receives it. In its ability to be read forwards or backwards, and on multiple pages simultaneously, BOO[K] decenters the conventional linearity of reading. Alternate readings are always present, which one can either attend to or ignore.

Johnson called his collaged works moticos, an anagram of the word osmotic, which, conveying ideas of permeability and transmission, emphasizes the works’ dynamic verbo-visual qualities. Johnson employs the paper’s transparency to play with notions of primary and secondary content. For example, on the right-hand page, behind the words Mother has a picture book we can read the ghosted words from the following page: May I see and mother? We can interpret this phrase as a request to see mother’s book or as an inquiry about the presence of the mother. Through strategically placed cutouts, Johnson alternately obscures and reveals text, evoking a tension between hidden and visible meanings. On the right-hand page, a rectangular opening has been cut into the page such that the fragment boo, in red ink, is revealed from the underlying page, while the k, in black ink, is present on the topmost page. In dividing the word in this fashion, Johnson ironically echoes these artists’ lived experience: bifurcated and differently legible according to one’s point of view.

The use of language as a tool of power was viscerally palpable to Cold War-era homosexuals, for whom this identificatory label was not merely descriptive, but a scarlet letter used to police and persecute them. Certain terms, such as heterosexual, became coterminous with normalcy and others, such as homosexual, coterminous with deviance. Revealing the dynamics of the process by which these ideological mystifications took place was a central problematic for these artists. In making clear that words mean differently in different contexts, they sought ways to reveal that all such labels – and the qualities they name – are mythologized as natural and enduring, rather than being recognized as the shifting and arbitrary product of social construction. As Slavoj Žižek explains, “one of the fundamental stratagems of ideology is the reference to some self-evidence – ‘Look, you can see for yourself how things are!’ ‘Let the facts speak for themselves’ is perhaps the arch-statement of ideology – the point being, precisely, that facts never ‘speak for themselves’ but are always made to speak by a network of discursive devices.”1

BOO[K]’s physical qualities literalize these artists’ interests by showing how language itself is never fixed but instead consists of a layering of meanings upon which the reader draws. BOO[K] is literally read through its pages, making visible the way in which a text always draws upon references that are external to it, becoming, as Roland Barthes claimed, a “tissue of citations.” By highlighting each individual’s agency in meaning-making, BOO[K] facilitates the reader’s recognition that vision is neither passive nor purely receptive—that what you see depends on where you sit. For homosexual artists during the Cold War, this possibility was key toward their larger goal of destructuring a homophobic culture organized around a very particular angle of vision concerning the “natural.”

During this era, one of the most socially regulated in US history, conformity was enforced and dissidence of any kind was not merely dangerous but, for some, practically suicidal. The height of the Cold War was marked by efforts not only to insulate America against threats from without, but also to neutralize threats from within. Difference was not just suspicious, but indicative of political threat. The apotheoses of these efforts was the Red Scare, a campaign to ferret out Communist sympathizers, and its counterpart, known colloquially as the Lavender Scare, initially designed to purge homosexuals from government service, but quickly marshaled against non-government employees as well.2

In 1947, President Truman signed an Executive Order creating the Federal Employees Loyalty Program, designed to identify and dismiss employees suspected of being “un-American.” While both McCarthy’s Senate committee and the House Un-American Activities Committee’s witch hunts were rooting out suspected Communists, an equally devastating purge was taking place against suspected homosexuals. In his studies on the cultural politics of the Cold War, Robert Corber has detailed the organized and systematic efforts to identify and remove suspected homosexuals from government service.3 Because homosexuals were believed to be more vulnerable to blackmail owing to their heightened need for secrecy, it was believed that they posed an exceptional threat to national security.

Making matters worse, the Senate Appropriations Committee, charged with investigating federal employment practices as they related to gay and lesbian workers, issued a report disputing the “popular stereotypes of the effeminate homosexual and the masculine lesbian.”4 The revelation that homosexuals might not conform to behavioral stereotypes led to an increased emphasis on their invisibility, heightening the scrutiny. In 1953, President Eisenhower issued an order stipulating that all homosexuals working for the government in any capacity be removed immediately from their posts. The indicting question shifted from “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” to “Information has come to the attention of the Civil Service Commission that you are a homosexual. What comment do you care to make?” Although the actions of the House Un-American Activities Committee and Senator McCarthy are much more widely known, in the end, as David Johnson makes clear in The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government, far more suspected homosexuals lost their jobs than did suspected Communists.

While these purges made clear the need for homosexuals to disguise their authentic selves behind a publicly acceptable front of heteronormativity, a less pernicious form of this self-silencing strategy was being adopted by legions of “men in grey flannel suits.” As William H. Whyte’s best-selling book of the era The Organization Man explores, the code of conformity imposed on American life in the ‘50s, particularly in corporate culture, necessitated if not actual conformity, then at least the outward appearance of it. Corporate workers quickly learned that to get ahead they must cultivate a carefully crafted public self that might be quite different from one’s more authentic private self. As a result, Jonathan D. Katz argues, heteronormative America was being similarly trained in the value of the closet as a mode of survival.5

In the midst of these social conditions, Abstract Expressionism was the prevailing artistic movement. It entailed the conflation of artist and viewer, in the form of an expression of the artist’s inner self that would be immediately and emotionally understood by the viewer. Planning was to be avoided, and spontaneity, accident, and improvisation were privileged as the unmediated expression of the artist’s psyche. The presumed direct correlation between artist and mark made the gestural brush stroke the hallmark of Abstract Expressionism; gesture and identity became discursively synonymous. It is easy to see why this would have been problematic for homosexual artists.

Among the solvent transfer images is one of a baby in a playpen. The baby may well be Rauschenberg’s son with Susan Weil, Christopher, who was born the year prior to this work, and who appears in other works such as Canyon (1959). Weil and Rauschenberg met at Black Mountain College, where he also met Cy Twombly; less than a year after he married Weil, Rauschenberg found himself falling in love with Twombly and left Weil and their infant son for a relationship with Twombly. By the time of Untitled (Mirror)’s creation, Rauschenberg and Weil were already separated. It was not an easy break, as Rauschenberg was torn by the conflict between the responsibility of marriage and family and following his heart. Thus even this image of a baby is made to mean multiply, standing as a symbol both of marriage and the heterosexual family unit, and of the dilemma the artist faced in wishing to live a life more true to himself, a life that meant being romantically involved with men.

Rauschenberg includes other images that similarly point to this dilemma, such as the solvent transfer of an Old Master Venus, which is a frequently recurring motif in Rauschenberg’s work. As Kenneth Bendiner notes, Rauschenberg reproduces a Cranach Venus in Levee (1955), a Titian in Odalisk (1955-58), a Velázquez in Barge (1962), a Michelangelo in Estate (1963), and a Rubens in Persimmon (1964), as well as others in Rebus (1955), Short Circuit (1955), Bicycle (1963), and Tracer (1964).6 Bendiner posits that the Venus transfers function “primarily as signs of love,”7 giving them an ironic twist considering Rauschenberg’s romantic interests.

The work’s title is drawn from a headline fragment from England’s daily tabloid, the Daily Mirror, and acts as a signpost to one of the work’s most significant thematics. Mirrors recur frequently in Rauschenberg’s work, adding layers of signification, whether within a transferred image, such as the fragment of Rubens’s Venus with a Mirror in Persimmon (1964); as an actual 3D object affixed to the surface, such as in Charlene (1954); or hanging from the work as in Minutiae (1954). At its most basic, the mirror is a trope of psychological self-awareness, from simple notions of self-reflection to Lacan’s Mirror stage, in which the child develops an awareness of its own subjectivity. For Rauschenberg, mirrors emphasize the individuated encounter rather than a universal or collective experience. In the works that include a physical mirror, the viewer’s reflection is incorporated into the surface of the works, materializing Rauschenberg’s emphasis on the centrality of the viewer. Moreover, since what is reflected changes with every viewing environment, Rauschenberg further destabilizes the idea of a work’s fixed and unchanging meaning, instead opening it up to an endless stream of potential significances. Finally, the mirror ironizes one of the prevailing ways in which homosexuality was then understood. Based on the Greek myth of Narcissus, who fell in love with his own image, Freud proposed that homosexuality was the result of a faulty object-choice in that the homosexual is attracted to someone whose gender matches his own: his mirror image.

As with many titles, the word Mirror serves as an organizing rubric guiding our contemplation of the work. As a word, Mirror is more noticeably reversed than some of the other pictorial elements, which spurs the viewer to consider the import of its reversal. Its adjacency calls our attention to the Statue of Liberty’s reversal, so subtle that one might not notice the flipped position of her arm holding the torch. Untitled (Mirror) is one of Rauschenberg’s earliest works made using the solvent transfer method, which would soon become the bedrock of his artistic practice. This method involves the transfer of an image from a printed source – most frequently newspaper and magazines – which is soaked with xylene or other chemical solvents, laid onto a new surface, and rubbed with a burnishing tool, transferring the ink from the source to the receiver. The source image is reversed on the receiver, a consequence which is usually incidental and without any symbolic import. However, the reversal here of the Statue of Liberty—our nation’s symbol of hope, opportunity, and freedom—carries implications of the myriad ways in which those privileges are often denied gay and lesbian individuals.

Solvent transfer, as a method, challenges the Abstract Expressionist celebration of the gestural in that neither the source nor the transfer is autographic. The mechanical reproduction of the images undermines the singularity of the gestural and rejects originality, a core tenet of High Modernist discourse. Jasper Johns, Rauschenberg’s partner after Twombly for more than six years, undertakes a similar rejection as one of his central themes. Johns’s preference for using pre-existing stencils to create letters and numbers, rather than hand-painting them, was a way of both acknowledging and subverting the fantasy that our tastes – what we might see as our deepest interiorities – are not in fact our own, but rather are constituted within a system of meanings mediated by power’s discourse. This is the very heart of Johns’s problematic.

Art critic Leo Steinberg raised this question in conversation with Johns:

I asked him about the type of numbers and letters he uses – coarse, standardized, unartistic – the type you would associate with packing cases and grocery signs.

Q: You nearly always use this same type. Any particular reason?

A: That’s how the stencils come.8

Johns’s response yields an important clue to his rhetorical strategy. Like Rauschenberg, Johns underscores the idea that meaning comes from a variety of sources beyond the authorial.

Johns’s efforts to distance his authorial self from the canvas can be seen in his choice of adopted motifs: flags, targets, letters, and numbers, each an impersonal symbol devoid of any emotional import. As he famously said, “I found that I couldn’t do anything that would be identical with my feelings. So I worked in such a way that I could say that it’s not me.”9 Numbers are one of Johns’s most common motifs, and 0-9 (1960) and Numbers (1960) are representative examples of the way he has approached numerals throughout his career. Typically they appear either singly or in a group, always in ascending order. Never do they appear out of order, or in a combination that might suggest a date, an address, or some other marker of personal significance. Equally important is the fact that numbers are symbols of abstract concepts, and thus have no indexical relation to objects in the world: their meaning relies on social construction. Part of the appeal is their ordinariness. As immediately recognizable objects, they are, Johns said, “things the mind already knows.”10 That familiarity opened up the canvas, giving him “room to work on other levels.”11

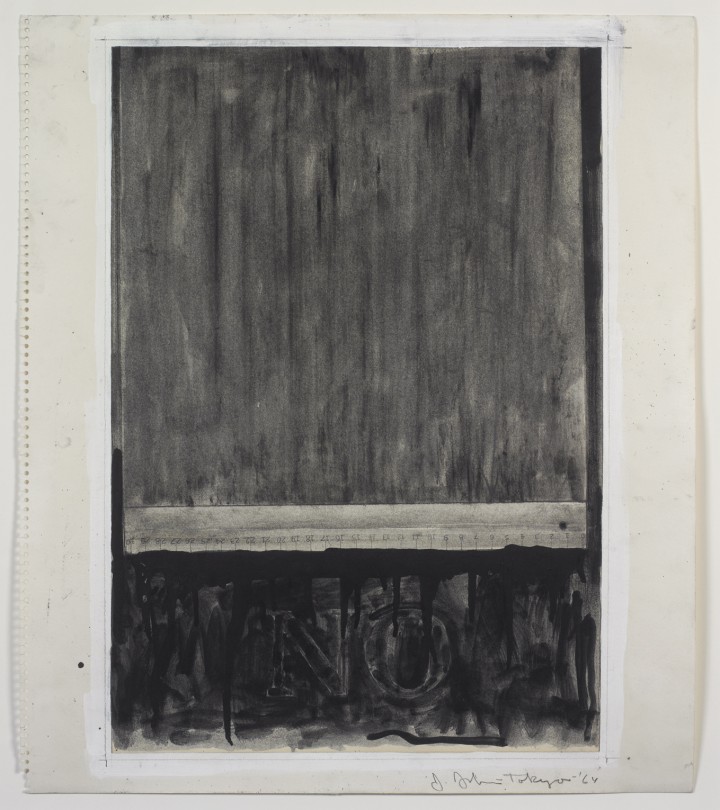

We can read NO as a negation, but a negation of what? As a word, NO is open, as easily against anything as it is against the idea of the authentic gesture. Johns’s interest in the dynamic interplay between language and image is underscored by an early work, 1957’s Book: an actual book, open and affixed to the canvas spine down, with its pages covered in red encaustic, a wax-based pigment. The red wax largely obscures the text, rendering it illegible. As Brian M. Reed notes, the significance of this piece turns on the pun red/read, which “links the artist’s act of creation and a viewer’s act of interpretation. Artist and audience are brought together by an artful use of language. As Johns has said, “You can come to see something through language that you couldn’t have come to see through looking.”12

Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel echoes Cage’s practice of mobilizing silence in his musical compositions to erase the typical power relationship between artist and viewer. By allowing silence to enter the performance, Cage brings the unique circumstances of each listening context into play, thereby letting sounds he cannot control supersede those that he can. For Cage and his fellow homosexual artists, silence served another crucial function: as a form of covert resistance to the dominant culture’s totalizing control. Recognizing that any actions perceived as openly oppositional would only elicit further repressive impositions of power, Cage and his cohort developed strategies, like silence, that allowed forms of camouflaged dissent, evading control by not being openly resistant.13

The Cold War politics of selfhood demanded a practice of not saying. In the opening of his 1949 essay “Lecture on Nothing,” Cage writes “I am here, and there is nothing to say” and then, in typical Cageian fashion, continues for 575 more lines. His point however, is not that there is literally nothing to say, but rather that he wants to draw our attention to the dynamics of power inherent in language and, in relinquishing this power, to transfer agency for meaning-making to the reader. At the heart of Cage’s aesthetic is a deeply ethical political project. In refusing the normal majority/minority operative binary, Cage erases the prevailing hierarchical dialectic of power, creating the possibility of multiple and shifting hierarchies. Elsewhere, Cage speaks against communication, in favor of conversation. Communication entails a unidirectional flow of ideas, a message to be conveyed and received, as opposed to conversation, which allows for the free exchange of ideas. Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel is a conversation with the viewer, who creates meaning from the various word and image fragments that Cage has provided.

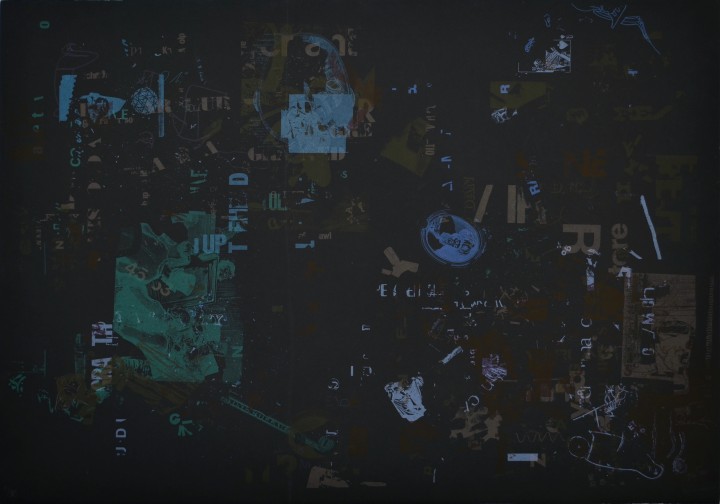

Cage frequently used chance operations in creating his works in order to eliminate his personal tastes, which he saw as necessarily delimited by what he already knew. Here the placement of words and images, their size, and their color were determined by the I Ching, an ancient Chinese chance-based system of divination. Devoid of any specific focus or narrative, the resulting surface invites the viewer’s eye to wander, taking in the word and image fragments and reworking them in endless combinations. In this way Cage silences his own voice and allows the viewer to complete the work. In the context of the Cold War, the notion of individual freedom was a conservative fundamental idea, one that ideologically differentiated us from the Soviet Union’s forced collectivity. By offering the viewer freedom to make meaning, Cage deftly camouflages his radical freedom in the terms of America’s most fundamental claim about itself.

Whether in his musical or visual compositions, Cage created opportunities for the production of a new form of subjectivity, one in which the viewer is not merely a consumer, but an active producer of meaning. This is the element that gives these works such subversive power. Cage enables viewers to perceive themselves and their relation to power in new ways and, in imagining these new relations, to discover new means of eluding power’s control. As is often the case with Cage, not saying anything at all said more than saying something in the first place, since the absence of statement forced the audience to embrace the freedom to make meanings on their own. As he wrote, “I have nothing to say, and I’m saying it.”

It is important to note that these artists were not engaged in a simple negation of the ideological constraints to which they objected: saying nothing in order to say everything is the hallmark of their praxis. A simple opposition merely upholds the majority/minority heterosexual/homosexual binary and reinscribes the very dialectic they seek to escape. Rather, by calling attention to the site of meaning-making itself, what theorist Ross Chambers calls the enunciatory situation14, these artists engaged the viewer in mediating the work’s meaning and making possible a plenitude of interpretations. Even in that culture of conformity, words meant differently to different audiences and language became a tool of the majority, used to enforce the definitions and social conventions that it privileged. When the meanings of love or family are used to uphold traditional majority values, what significance can those words have for those who are excluded by them? When simple everyday words like these carried treasonous import, it is easy to see why homosexual artists would have sought to create the prospect of new meanings for old words. This began the shift toward the viewer, or reader, as the maker of meaning.

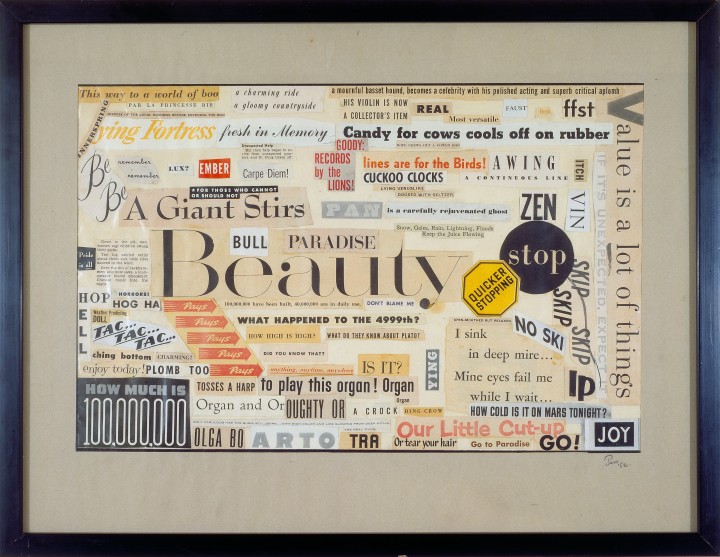

Open-Mouthed but Relaxed is composed of individual words, fragmented words, sentence fragments, and complete sentences, many in the form of questions. Jess called his collages paste-ups, acknowledging their playfulness in image and method—a grown-up version of children’s paper collages. The whimsical phrase “our little cut-up” could apply equally to the collage or to Jess himself. The cluster of phrases—cuckoo clocks, lines are for the birds, awing a continuous line, (which can also be read as a wing), or, below it, skip skip skip, no ski, and ip—evoke a playfulness with language that calls to mind the neologisms, repetitiveness, and stream of consciousness employed by Modernist writers such as T.S. Eliot, William Faulkner, and James Joyce. But Jess takes more from Joyce than simply an experimental approach to language. In the mid-1940s, Jess had discovered Joseph Campbell and Henry Morton Robinson’s A Skeleton Key to Finnegan’s Wake, which untangled Joyce’s densely woven web of references, puns, metaphors, and symbols. This literary exploration awakened Jess to language’s pliability, which would become a standard convention of his own work.

The juxtaposition of fragments in Jess’s collage allows the viewer to treat each as its own element, or to link them together into readable sentences. For example, in the center of the work, one fragment, Pan, precedes another fragment, is a carefully rejuvenated ghost. The Greek god Pan (half-man, half-goat) was, according to some mythic traditions, one of the only Greek gods to actually die, while according to others he did not literally die, but stood figuratively as a metaphor for the death of pagan religion attendant to the rise of Christianity. Duncan and Jess shared a love for myth, and their work demonstrates a profound knowledge of both Greek and world mythology. Typically accompanied by a band of satyrs, Pan is associated with a raw animalistic sexuality and is a symbol of sexual desire. In referring to Pan here as a “carefully rejuvenated ghost,” Jess may attempt to breathe new life into the study of myth, or to comment on the caution that his personal relationship with Duncan necessitated. The word ghost implies a veiled opacity, which mirrored the alternately visible and invisible nature of their life as a couple. The play with sexual double entendre can, of course, also be seen in the multiple iterations of the word organ. Rebecca Solnit has written extensively on San Francisco’s ‘50s and ‘60s counter culture, including Jess and Duncan. She writes of Jess, “His work was openly gay in its appreciation of male nudes and openly unmasculine in daring to be pretty, delicate, playful — all things about as far from Jackson Pollock as you could get.”15 Finally, the preponderance of questions helps chart Jess’s investment in giving power to the reader to make meaning: after all, he does not supply the answers to any of his questions, leaving them open-ended.

Merging the visual with the textual, concrete poetry presents a coterminous relationship between text and image: reading the words is not sufficient for understanding; one must see the words in order to apprehend the poem. In many cases, were one to read the text aloud the meaning of the poem would be lost. The term concrete, as applied to the arts, predates its use in naming a particular type of poetry by approximately two decades. As early as 1930, Theo van Doesburg published Art Concret, a journal advocating a style of non-referential painting that emphasized ideas. In the 1940s, the term was applied to a new form of music composed of noise, such as Pierre Schaeffer’s 1948 “Concert of Noises.”16 We can trace as far back as Ancient Greece the existence of pattern poems, which take the shape of the idea reflected—funeral odes that look like altars, battle odes that look like axes—but in the mid-1950s, the designation concrete poetry arose nearly simultaneously with the Noigandres Group in Brazil and Eugen Gomringer in Germany.17

The term is often colloquially applied to any poem to which the shape of the poem is integral, though its more specific usage applies to the particular form of visual poetry that emerged in this particular historic moment and to poems in which the layout of the text creates a shape, such that the poem as a whole becomes a visual analogue to the idea expressed therein. As such, the placement of the words takes precedence over syntactical concerns, and traditional poetic strategies such as rhythm, meter, and metaphor give way to spatial arrangement, negative space, and visual architecture.

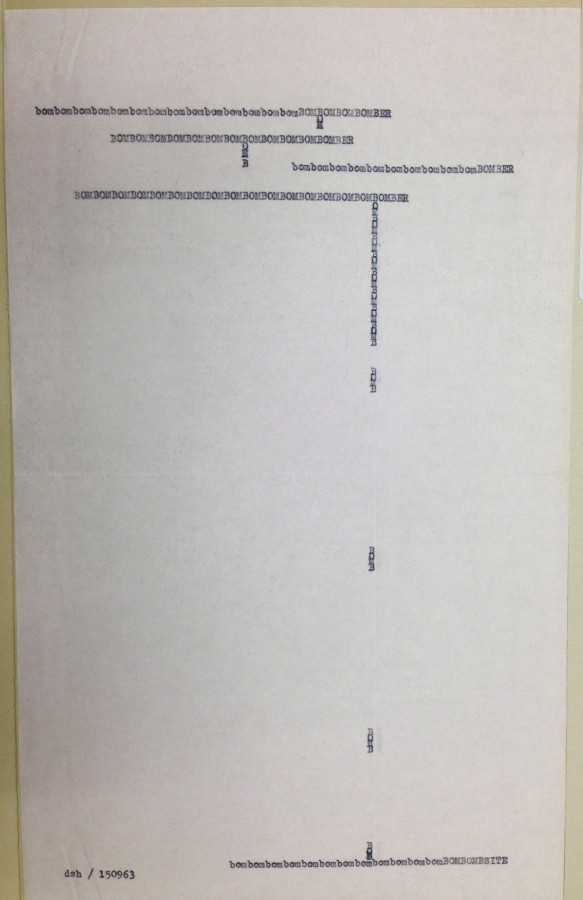

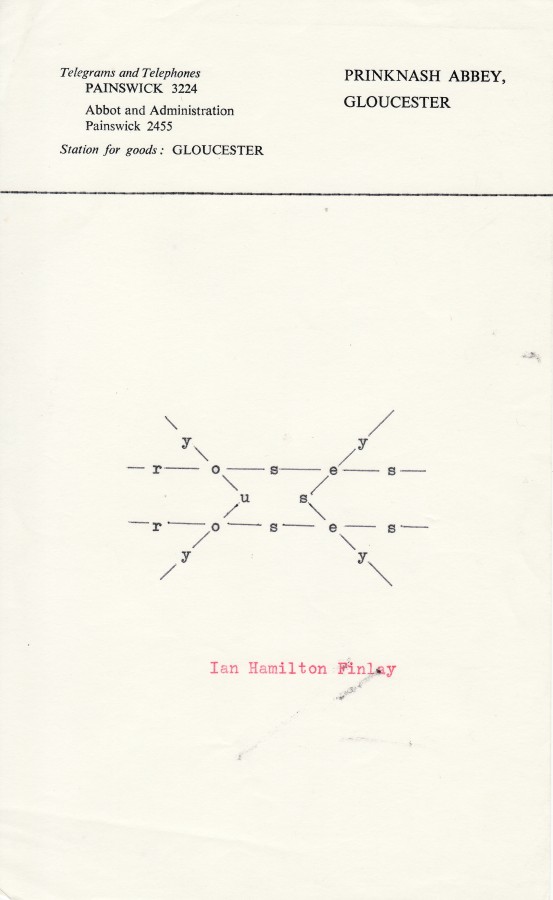

While a work like bombombomb… relies on the direct relation of word to image, Houédard, Finlay, and other poets also created works that shifted away from the visual object toward an emphasis on the process of signification and the networks of correspondences that constitute meaning. Houédard’s visual poems relied on what he referred to as their “pluritotality” – the sum of their multivalent meanings, denotative and connotative, sincere and ironic. In these visual poems, the investment is in the variety of meaning available within the work, and in the system of relationships across the entire work, as opposed to that of one line or verse to the next, as in more traditional poetic forms. Houédard often materialized these relationships by employing a single word oriented in multiple directions, or by pivoting multiple words from a single letter, much like in a crossword puzzle. As the reader is thus required to read multiply, these poems make manifest the ways in which such a text – and by extension, all texts – may be open to multiple meanings.

Houédard was an unlikely leader of the concrete poetry movement. A Benedictine monk from England’s Prinknash Abbey, he published extensively in small-press literary journals, including Finlay’s Poor. Old. Tired. Horse., and maintained a correspondence with many of the leading poets and language innovators of his day, even collaborating with some of them, including John Cage, Gustav Metzger, and Yoko Ono. Educated at Oxford before ordination, Houédard exhibits a profound intellectual engagement in his critical writings, citing Postmodern theorist Rosalind Krauss and philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein with as much facility as biblical verse.

Almost all of Houédard’s works were composed on his portable Olivetti Lettera 22 typewriter, many on Abbey letterhead, and often using the different colored ribbons available for this model, an aspect of his work that was frequently lost in publication. Houédard’s use of the typewriter gave rise to the neologism “typestracts” to describe his poems, and he is recognized as one of the leading practitioners of typewriter art. Like Finlay, he alternated between concrete poetry, such as bombombomb… and typikon by, and visual poetry, such as cover cased / case covered and prayer poetry, all from 1963.

Houédard was a great admirer of the Beats, and he read extensively in and corresponded with Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, and Allen Ginsburg; his writing reflects the jazz-inflected syntax and frank, often homoerotic, sexuality of the Beat aesthetic. Houédard’s prayer poetry (1963) links a variety of experiences — poetry, jazz, and sex — to the sublime quality of prayer. The poem emphasizes the degree to which Houédard was invested not in determining meaning for the reader, but in making the reader aware of their own freedom to discover new meanings. In the catalogue for the 1965 exhibition Between Poetry and Painting at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, in which his work was featured, Houédard explained his perspective on language’s malleability: “dictionary (convention) as language coffin – this word/poem means the WAY we use it – we (not them) convene its meaning.”18

That we can read the words in cover cased / case covered in a sexual manner, against their common meanings as simple adjectives describing the physical qualities of objects, demonstrates Houédard’s investment in opening language to a “pluritotality” of meaning, even, and perhaps especially, if some of these meanings run counter to those privileged by dominant culture. Just as the alternate readings of jazz/jizz pivot on the r, the words in cover cased / case covered pivot on the totality of each individual word in relation to the whole. By enabling each word to convey both a traditional and a dissident meaning, Houédard shows that it is possible to escape the language coffin. Like his collaborator Cage, Houédard facilitates our understanding of language as an instrument of control wielded by dominant culture and the discovery of a radical freedom precipitated on our redeployment of language against it. His minimalist typestracts exemplify his desire to create “jewel-like semantic areas where poet and reader meet in maximum communication with minimum words”19: areas in which we can discover the power to create meaning, and with it, the power to create new realities.

In her analysis of Frank O’Hara’s poems, Marjorie Perloff calls words that function in this way floating modifiers because they “point two ways.”20 We can see this in these lines from O’Hara’s poem Morning:

I’ve got to tell you

how I love you always

I think of it on grey

mornings with deathin my mouth the tea

is never hot enough

The phrase “in my mouth” refers both backward to death and forward to the tea. While the reader is free to choose referent with which to align the phrase, it nevertheless resists an absolute joining, leaving meaning forever open to either possibility. Perloff’s analysis of the flexibility of words in O’Hara’s poetry offers an analogy to explain how meanings circulate and are elevated by hegemonic culture to reinforce ideology. In Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory, Ernesto Laclau articulates a post-Marxist analysis of social conflict, arguing for a more expansive explanation contingent upon social antagonism rather than class struggle. At the core of Laclau’s argument is the notion that “meaning does not inhere in elements of an ideology as such – these elements, rather, function as ‘free floating signifiers’ whose meaning is fixed by the mode of their hegemonic articulation.”21 The artists included in this exhibition destabilize hegemonic power by revealing its instability and impermanence.

Decentering authorial control and focusing on networks of correspondences allows each reader to determine their individual experience of the poem. In Finlay’s y-o-u y-e-s, rather than following the traditionally prescribed left-to-right, top-to-bottom flow, the reader can choose which line to read first and how to travel through the poem. Reading the poem puts the reader in the position of contravening the conventional rules of reading, which awakens the awareness that alternatives are possible. This awareness lies at the heart of the work’s political potential. When we are able to recognize that it is possible to read against conventional norms, we realize that other norms may be similarly challenged, other rules similarly breached, and it becomes possible for us to imagine other relationships with power.

The ability to imagine other possibilities is the prerequisite to creating them. Magician Jamy Ian Swiss describes how our preconceived notions permit the magician to perform sleights of hand. In a trick called the color vision box, a six-sided cube with each side a different color is placed by the mark into an empty box with a chosen color on top, followed by the lid. The box naturally has a disguised feature: a movable lid. As it is handed back to the magician, he covertly slides the lid of the box such that the box’s top is now its back, revealing the mark’s chosen color to the magician, while the box appears unmanipulated. It is our expectation about the nature of boxes and lids that enables the trick to succeed. As Adam Gopnik explains, “the concept of rotating an object, though obvious, is in some way defeated by our familiarity with boxes and lids – a lid always goes on top.”22 This trick nicely demonstrates one of Swiss’s maxims: “magic only ‘happens’ in a spectator’s mind…[e]verything else is a distraction.”23 The magician’s covenant with the viewer hinges on indeterminacy. To be successful, a trick must offer insufficient evidence of its execution, such that the viewer can conceive of multiple explanations, none of them definitive.

This inconclusiveness lies at the heart of the artworks included in this exhibition. In order to catalyze viewers’ recognition of their own agency, it is essential that each work offer not simply an oppositional reading, but rather an open-ended range of possibilities. In a 1961 essay on Rauschenberg, Cage explores the variety of ways in which Rauschenberg’s work can be read. Recognizing the shifting meanings that could be found in his subject’s canvases, Cage writes, “Over and over again I’ve found it impossible to memorize Rauschenberg’s paintings. I keep asking, ‘Have you changed it?’ And then noticing while I’m looking it changes.”24

1. Slavoj Žižek, “The Spectre of Ideology” in Mapping Ideology, ed. Slavoj Žižek and Nicholas Abercrombie (London, Brooklyn: Verso, 2012), 11.

2. David Johnson, The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

3. Robert Corber, Homosexuality in Cold War America: Resistance and the Crisis of Masculinity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997) and In the Name of National Security: Hitchcock, Homophobia, and the Political Construction of Gender in Postwar America (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993).

4. Corber, In the Name of National Security, 62.

5. Jonathan D. Katz, “Passive Resistance: On the Success of Queer Artists in Cold War American Art” L’image 3 (December 1996): 119-142.

6. Kenneth Bendiner, “Robert Rauschenberg’s ‘Canyon’,” Arts 56 (1982): 57-59.

7. Ibid, 57.

8. Leo Steinberg, Other Criteria: Confrontations With Twentieth-Century Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), 32.

9. Kirk Varnedoe, ed., Jasper Johns: Writings, Sketchbooks, Notes, Interviews (New York: Museum of Modern Art and Abrams: 1996), 145.

10. David Sylvester, About Modern Art: Critical Essays 1948-1997 (New York: Henry Holt, 1996), 222.

11. Ibid.

12. Brian M. Reed, “Hand in Hand: Jasper Johns and Hart Crane,” Modernism/Modernity 17.1(2010): 24.

13. Jonathan D. Katz, “John Cage’s Queer Silence, or How to Avoid Making Matters Worse,” Gay and Lesbian Quarterly 5.2 (1999): 231-252.

14. Ross Chambers, Room For Maneuver (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991).

15. Rebecca Solnit, “Inventing San Francisco’s Art Scene: 1950s Bohemians Altered the World from Their Lofts in the City,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 25, 2004, E1.

16. Felipe Boso, “Concretism” in Corrosive Signs: Essays On Experimental Poetry (Visual, Concrete, Alternative). ed César Corzo Espinosa and Harry Polkinhorn (Washington, D.C.: Maisonneuve Press, 1990), 46-47.

17. Johanna Drucker, Figuring the Word: Essays on Books, Writing, and Visual Poetics (New York City: Granary Books, 1998).

18. Dom Sylvester Houédard, “Statement by Dom Sylvester Houédard” in Between Poetry and Painting (Institute of Contemporary Arts: London, and London: W. Kempner, 1965), 55.

19. D.S.H., Charles Verey, and Ceolfrith Gallery. Dom Sylvester Houédard (Sunderland, Durham: Ceolfrith Arts Centre, 1972.), 47.

20. Marjorie Perloff, Frank O’Hara Poet Among Painters (Austin and London: University of Texas Press, 1977), 56.

21. Slavoj Žižek, “The Spectre of Ideology” in Mapping Ideology, ed. Slavoj Žižek and Nicholas Abercrombie (London, Brooklyn: Verso, 2012), 12.

22. Adam Gopnik, “The Real Work: Modern Magic and the Meaning of Life,” New Yorker March 17, 2008, 66.

23. Adam Gopnik, “The Real Work: Modern Magic and the Meaning of Life,” New Yorker March 17, 2008, 58.

24. John Cage, “On Robert Rauschenberg, Artist and his Work,” Silence: Lectures and Writings, 50th Anniversary Edition (Middletown, CT.: Wesleyan University Press, 2011), 102.