N. Elizabeth Schlatter

PDFGabe: Change equals death!

Judy: What kind of bullshit? That’s just a bullshit line! Maybe you fool your twenty-year-old students into thinking that’s some kind of a, an insight or something, but it means nothing! Change is what life is made of! Change — if you don’t change, you don’t grow; you just shrivel up!

With his typical brevity, wit, and exaggeration, Woody Allen’s character Gabe, in the 1992 movie Husbands and Wives, laments the changes he witnesses in his friends’ relationships and his own crumbling marriage. His wife, Judy, played by Mia Farrow, likewise responds in a manner predictable for her character — exasperated, emotional, but like Gabe, declarative. Of course, they are both correct. Change often results in the death or loss of something, or perhaps of a portion or aspect of something, but without change, things die completely.

The ability to change is crucial to the survival of both language and art. Innovations in technology within the last several years have spurred evolutions in our use of the English language, evidenced most clearly (and to some, regrettably) by the invention of “texting.”1 New definitions of the word text, as a noun meaning “a text message” or as a verb “to send a text,” have followed the example of the invention or resuscitation of other words influenced by previous developments in technology.2 Words like phone, fax, and e-mail began as nouns and eventually served as verbs as well. However, text works as either a verb or a noun yet also refers to its own content. Whereas a phone call is composed of the spoken word, and an e-mail consists of text, a text message is composed of itself, namely “text,” meaning written or printed words.

The popular media often voices concerns by people worried that texting and its countless abbreviations (e.g. LOL and L8R) will result in the end of proper spelling, attention spans, civility, privacy, relaxation, and good driving skills. Yet such fear regarding new forms of communication dates back at least to the ancient Greeks. In Plato’s dialogue Phaedrus, Socrates criticized the invention of writing (as opposed to the spoken word), arguing that it had made men intellectually lazy, as they were free from committing information to memory. According to Socrates, men who can rely upon written information instead of memorization, “will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without reality.”3

Echoing Socrates’s concerns, contemporary critics fear that the always-accessible Internet, and the handheld mobile devices by which we access it, make us stupid because we don’t have to remember anything.4 Texting parallels this intellectual downfall in its attack on the English language. However, British linguist David Crystal argues that new technologies enable linguistic creativity and that texting in particular is the manifestation of language’s plasticity. In 2008 Crystal wrote, “In texting, what we are seeing, in a small way, is language in evolution.”5 He cites studies in which texting actually increases and improves childhood literacy, he discusses how individuals have different styles of texting that reveal their backgrounds and aspirations, and he quotes poems written via text message to exemplify creativity in this new medium.

So what does this mean in terms of looking at art that incorporates text? Or, as is the case with a few works in Art=Text=Art, art that is about the obvious lack of text? When considering text in art, we should bear in mind that for many of us, our experience with text today is different than it was just a decade ago. Thanks to technology, and especially to text messages and e-mail, writing and reading have become a communicative intrusion in spheres where it previously did not appear, such as during a conversation or a lecture, a drive, a business meeting, in the bedroom and bathroom, at the gym, and so on. It is so ubiquitous that to its many users it has become invisible. This fluid and boundless connection to text influences both the creation of text-based art made in the twenty-first century and the reception of similar artwork made in prior years.

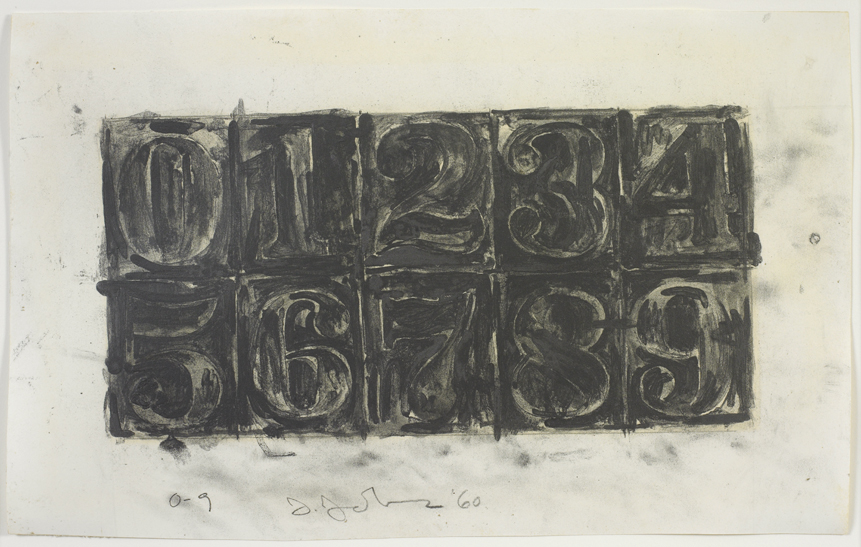

This is not to imply that art created since the advent of e-mail, chat-rooms, and texting is superior to historical works incorporating text, such as the stunningly gorgeous illuminated manuscript the Book of Kells, dating to the eighth century CE. Neither should we assume that contemporary viewers, writers, or readers are more intelligent or perceptive than those in the past. After all, ancient cultures such as the Mayans, Chinese, and Egyptians created highly complex scripts that intertwine image, word, and meaning. The twentieth century alone boasts an impressive roster of artists who incorporated text in their work in novel and influential ways — from Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp, to Jasper Johns and Joseph Kosuth, to Jenny Holzer and Jean-Michel Basquiat, to Glenn Ligon and Shirin Neshat (to name but a few) — resulting in a staggering amount of critical commentary on this topic by scholars, artists, and curators.

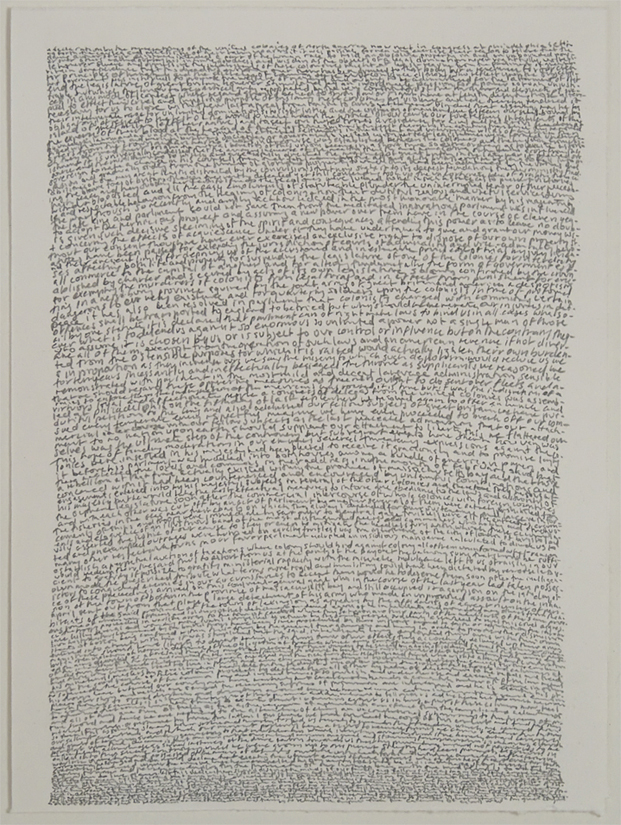

Due to their evolving relationship to text, contemporary art viewers bring an expanded range of interpretation to their “reading” of artwork that incorporates text. For example, compare William Anastasi’s two drawings titled Word Drawing Over Short Hand Practice Page, both from 1962, with Annabel Daou’s The Declaration of the Cause and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, from 2006. All three works feature the artists’ handwriting and content originally authored by someone else. The former includes shorthand exercise sheets and the latter is a handwritten copy of a 1775 document prepared primarily by Thomas Jefferson to explain why the colonies had begun arming themselves in the lead-up to the Revolutionary War.

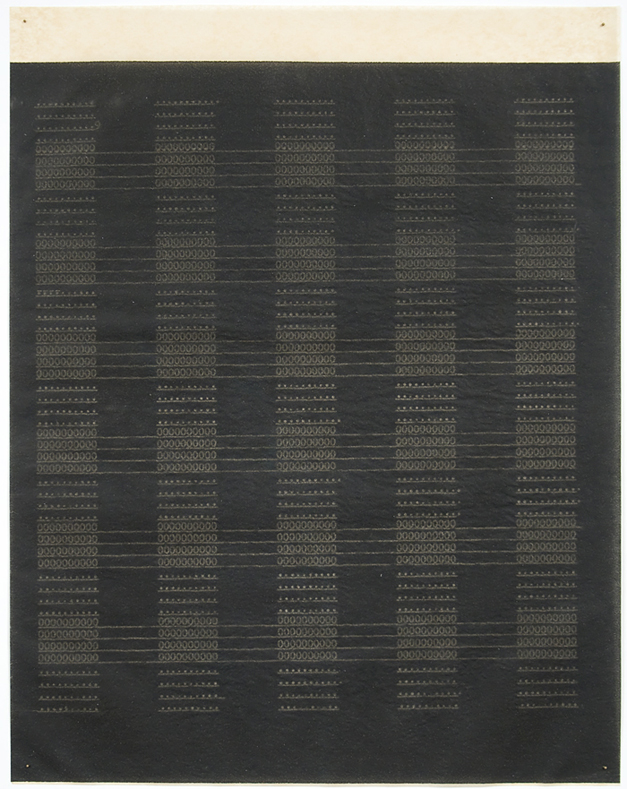

Anastasi, along with other so-called first-generation text artists such as Lawrence Weiner, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Barry, employed characteristics and strategies that tested the definition of art, such as immateriality, temporality, de-skilling, and de-authoring. These artists explored modern currents in philosophy and semiotics, interrogating the relationships between language, image, and meaning. The pre-printed shorthand symbols in Anastasi’s Word Drawing Over Short Hand Practice Page bear no relation to the longhand words the artist wrote next to the symbols, and this combination of words and symbols challenges the viewer to contemplate how meaning is personalized and conveyed in text. However, many observers today would likely consider shorthand an antiquated skill, if they even recognize what shorthand looks like at all. Thus, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, Anastasi’s two drawings not only exhibit semiotic connotations, they also suggest the diminishing utility of systems of handwriting in particular (shorthand and longhand) as a means of notation and communication.

Daou’s transcription of a historical document written at the beginning of the American Revolution is initially visually intriguing because of the large amount of handwritten text squeezed onto a relatively small piece of paper. When was the last time any of us have written so much by hand? And why copy in longhand a document that surely exists in printed form? Daou’s choice to handwrite in 2006 comes from motivations different from Anastasi’s choice to write in cursive in 1962. With the pervasive use of laptops, smartphones, and touchscreen tablets, combined with the free availability of historical documents on the Internet, to write a pre-existing text in longhand is a means to internalize that text both mentally and physically. This important link between text and hand — as a highly personal, time-consuming, and out-dated mode of communication — is readily but perhaps not consciously recognized by a contemporary viewer. This subtext of hand-scripted words contributes to the depth of meaning in Daou’s work, particularly when combined with factors such as the artist’s personal history (Daou was born in Lebanon and lives in New York), American history and politics, and, like Anastasi, semiotics.

In light of the blistering pace at which communications technology is evolving and the delivery of text via computers, smartphones, and e-readers, there is a possibly unintended but nonetheless strong sense of nostalgia pervading some of the art in Art=Text=Art. Donald Evans’s stamps from the 1970s that he created for imaginary societies, Ray Johnson’s mail art from the 1970s and 1980s, and Buster Cleveland’s ART FOR UM subscription series from the 1990s are no less fascinating today, but it is difficult to view them now without being reminded of the waning usage of the postal service. A few works made within the past ten years purposely incorporate means of recording, delivering, and receiving text that are declining in popularity. By using aging and yellowed pages or endpapers from books, John Fraser and Suzanne Bocanegra suggest opaque narratives with materials that are instantly recognizable and evocative. Allyson Strafella and Stefana McClure employ the unmistakable mark of typewritten impressions yet render them ineffective as communicative means. Karen Schiff references the structure of the placement of text and image in newspapers and illuminated manuscripts. These later works of art almost seem to negate text altogether, to promote the contemplation of the role of text in our lives by rendering it incomprehensible or absent where it should normally occur.

New communication technologies also foster new patterns of reading, specifically the literal physical act of moving the eyes to locate and recognize meaningful letters, words, and sentences. For example, frequent Internet users learn to “power browse,” rapidly skimming over text and images on a website to find the most relevant or interesting content. While efficient for seeking discrete bits of information, this style of reading may preclude the capacity for content retention and for a deeper comprehension and engagement with longer texts, such as novels.6

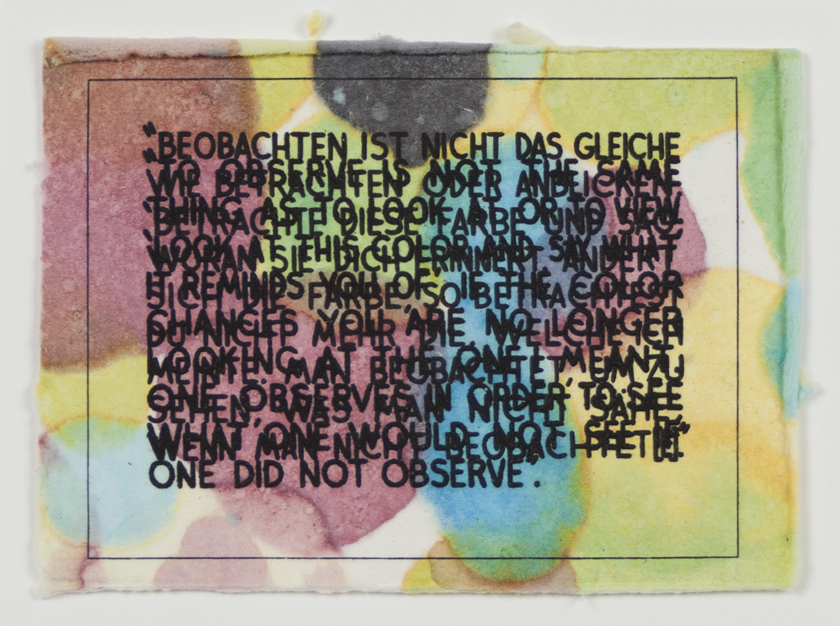

Several artworks in the exhibition remind us that reading is a learned physical activity that adapts to visual obstacles. Mel Bochner’s series of monoprints entitled If the Color Changes…, from 2003, feature rectangles or ovals of brightly colored inks, on top of which he has printed in black sans-serif capital letters a quotation from the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s unfinished work Remarks on Colour, from 1950-51. The excerpt is printed in both English and German, with one translation overlapping the other. Bochner is playing with ideas about the opacity and transparency of language (a constant theme in his work), the definition of color, and the inability to simultaneously “see” a work of art aesthetically and read text that exists on or within the same visual plane. Although Bochner’s prints seem most obviously to be about the subjective nature of words and of color, they are also about reading. One must visually tease the words out from under each other to read and comprehend the quote.

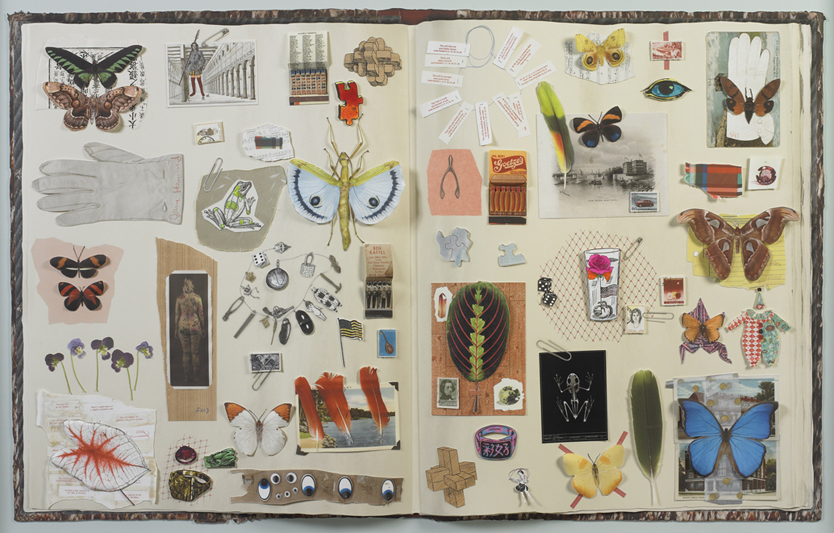

Both Cy Twombly’s Untitled (1971) and John Waters’s 35 Days (2003) test the limits of legibility in handwritten forms.7 Ed Ruscha’s Gray Sex (1979) and Susanna Harwood Rubin’s 102 boulevard Haussmann (2000) exploit the mind’s automatic capacity to cognize words with minimal visual cues and to then immediately imbue those words with personal references. Alternately, within the context of Art=Text=Art a few works suddenly become more “readable” or at the very least more textual than they might be if displayed alone. Examples include Jane Hammond’s Scrapbook (2003) composed of a selection of elements from her personal visual vocabulary; Christine Hiebert’s three study drawings, Untitled (Brand Markings) from 1998-99, which feature what appear to be newly invented letterforms; and Joel Shapiro’s Untitled (1969), with small fingerprints on a grid suggesting a potentially disturbing record keeping of human activity.

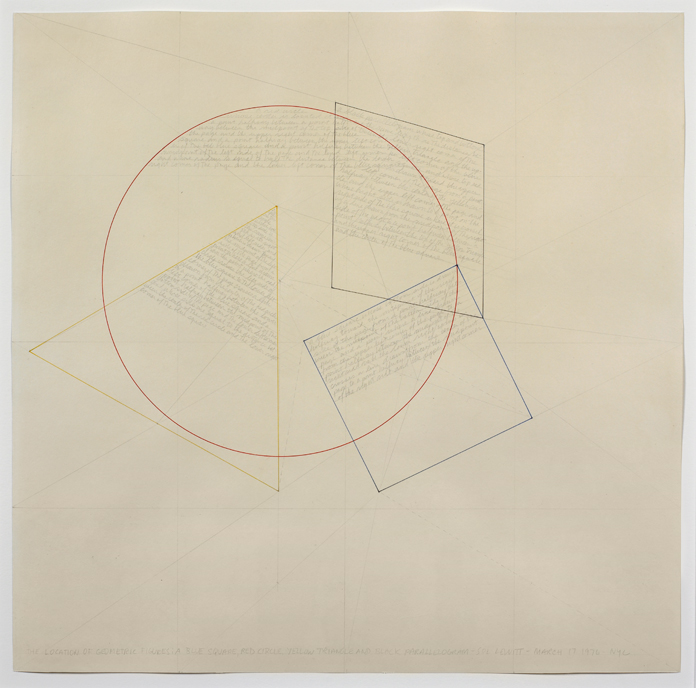

Finally, several of the pieces in Art=Text=Art relate to data visualization. Data visualization has been around for centuries,8 but the explosion of computer-assisted data visualization over the past ten years — from relatively simplistic word clouds to complex and interactive infographics — as well as its increasing use in the popular media, minimizes the conceptual leap from information to static visual forms. Older examples from the exhibition include Mark Lombardi’s Casino Resort Development in the Bahamas c. 1955-89 (Fourth Version) (1995), which diagrams a complex and corrupt network of power relations and money flow between organizations and people, and choreographer Trisha Brown’s Untitled and Drawing for Pyramid (both 1975), which were created to help her dancers visualize the concepts of accumulation and de-accumulation of movements in a performance.

A few contemporary works in Art=Text=Art relay information in a similar fashion but seem particularly poetic because of their embodied, personal interpretations, their irregularities in transcription as opposed to standard algorithmic constructions, and their apparent lack of practical purpose outside of artistic expression. Jill Baroff’s Untitled (Tide Drawing) (2006) is part of a series of works informed by recorded water levels at different locations during a period of about two or three days, yet the image seems more focused on emulating the overall sense of the rhythm of waves than conveying actual measurements. Suzanne Bocanegra’s Brushstrokes in a Victorian Flower Album: Long Headed Poppy (2000) mimics and categorizes the brushstrokes used by the illustrator in a nineteenth-century publication. In her artist’s book Breaths #1 (2010), Jill O’Bryan punctured sheets of paper with a pin, each hole marking one breath taken by the artist, and then rubbed the raised portions of the paper with graphite. But O’Bryan’s intent is not to record an action or series of actions but rather to refer to the fluidity of images and to the concept of air as floating and moving through bodies, just as it moves through the holes in the book when one turns the pages.

Situating the art in Art=Text=Art within the framework of new modes of textual communication underscores the continued relevancy of art incorporating text. The older works from the 1960s to 1990s maintain their original content but also acquire new import thanks in part to the role of text in today’s society. Meanwhile the most recent works were created amidst the infiltration of text into our everyday lives, and that contemporary context pervades both the production and the reception of the work.

Ultimately, Mia Farrow’s character’s pronouncement about change rings true for both language and art. Flexibility ensures the continued use of English despite novel modes of communication. Art, however, progresses somewhat differently. While the kind of art being made changes according to the times in which it is created, most art, once made, doesn’t radically change (except, of course, when one of the primary characteristics of the art is change). But viewers’ perceptions do change. And the art that withstands time is, like language, ideologically flexible enough to retain a core content while accommodating new meanings and interpretations. Experiencing a contemporary exhibition about text in art allows us to consider that flexibility from a distinct vantage point, and leads us to wonder how people will see and “read” the same art in the future.

1. For an extensive analysis of texting’s impact on language see David Crystal, Texting: The Gr8 Db8 (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2008). This essay for Art=Text=Art refers only to the English language, but Crystal’s book provides examples of inventions and adaptations occurring in dozens of languages worldwide.

2. Variations of text as a noun meaning “wording of anything written” date back to the fourteenth century and as a verb meaning “to write in text letters” as early as the 1590s. However, in 2005 dictionary sources added the definition “to send a text message.” Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. (accessed: 3 July 2011)

3. For an interesting analysis of the discussion of the written word in Plato’s Phaedrus and its relevance to electronic media today, see “If Socrates Had E-mail,” a speech given in February 1997, by Kenyon College president, S. Georgia Nugent.

4. One oft-cited example of this concern is discussed in Nicholas Carr, “Is Google Making Us Stupid: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains,” The Atlantic July/August 2008. (accessed: 3 July 2011).

5. David Crystal, “2b or Not 2b,” The Guardian 5 July 2008. (accessed June 25, 2011). Crystal defends his theories in this entertaining clip from the BBC television show “It’s Only a Theory,” originally broadcast in 2009. Other linguists have noted that technology can also help vivify nearly extinct languages. See Margaret Rock, “ITTO: Teenagers Revive Dead Languages Through Texting,” Mobiledia, 29 June 2011. (accessed 13 July 2011)

6. For references to a British study of online reading habits see Carr, op. cit.

7. Waters collects Twombly’s art, and he referred to Twombly’s handwriting as “both violent and erotic,” in a lecture at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2009. For a description of that talk see Howard Kaplan, “John Waters on Cy Twombly,” Eye Level, Smithsonian American Art Museum, 30 March 2009. (accessed 24 June 2011)

8. For the history and analysis of data visualization, see Edward Tufte, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press, LLC, 2001).