Generally the drawings have been made just to make the drawing, and the simplest way for me to do it was to base it on a painting which existed, although they generally don’t follow the painting very closely.

– Jasper Johns, interviewed by Walter Hopps, 1965 1

Jasper Johns distinguishes himself from other artists by almost exclusively drawing after the motif has been rendered in painting or sculpture.

– David Shapiro, from Jasper Johns: Drawings 1954-1984 2

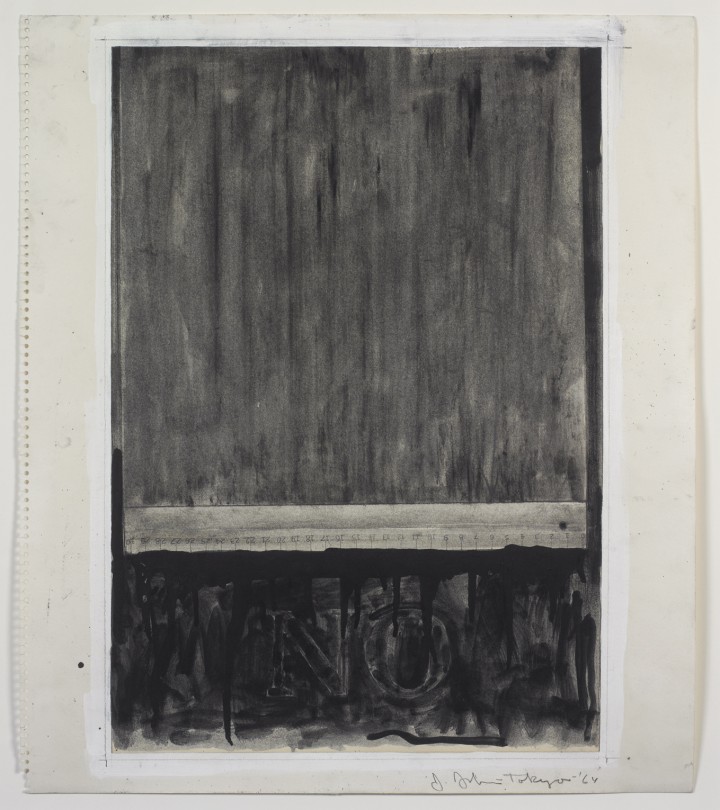

What does it mean to make a drawing after a painting? Chronologically speaking, Johns made this drawing titled No in 1964, three years after he made a painting also titled No, dated 1961. The drawing is one of a pair with similar content that the artist created while living and working in Tokyo for about two months in 1964. The two drawings and the 1961 painting were shown together at the Minami Gallery in Tokyo in 1965, and both drawings were listed in the exhibition catalogue with the same title: Drawing for “No.” These drawings relate to notes found in the artist’s sketchbook from that period, in which he references the idea that the Japanese phonetic “no” signifies the possessive “of.”3

Traditionally, the relationship between drawing and painting is one of progression. That is, ideas are “worked out” in preliminary drawings, and the conclusions manifest in a final painting. Barbara Rose was one of the first critics to analyze Johns’s reversal of this order. She wrote that his drawings and prints, created after paintings and sculptures with similar iconography, allowed him to push certain ideas to their aesthetic conclusions, enabled largely by the inherent flatness of the surface of paper.4

Comparing the 1961 painting No and the 1964 drawing No confirms Johns’s own comments to the curator Walter Hopps (cited above) regarding his atypical approach to the relationship between the two mediums. Although the drawing and painting both share a grayish tone and the appearance of the word NO in the artist’s favored stencil font, the drawing features a combination of additional motifs that the artist was using in his paintings from around this time.5 These include a ruler being dragged across the surface; the word scrape drawn above the ruler, with a vertical line running from the top of the paper to the word; and an arrow from the e in scrape down to the top of the ruler. In his paintings Passage (1962) and Out the Window Number 2 (1962), for example, Johns attached actual rulers to the canvases, incorporated arrows, and scribed the word scrape.

However, unlike the physical rulers fastened to Johns’s canvases, the ruler in the drawing No is a visual representation composed of three lines, a band of lighter gray gouache and liquid graphite, and some numbers written in pencil, spaced appropriately to denote centimeters.6 There is no rendered dimensionality to the object, but the viewer recognizes this form as a ruler through linear and textual clues and through its perceived activity, ostensibly measuring the width of the paper and scraping the liquid medium down the piece of paper and onto the word NO.

Around the time he made this drawing, Johns was interested in the Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s assertions that a word derives meaning through the context of its use and, likewise, that an object can be identified by its use versus its name. In the drawing No, the ruler, much like Johns’s flags and targets in earlier works, is a tool rendered useless; it cannot perform its intended function because it is part of an artwork. Here we experience an optical fallacy—that is, the illusion of the object pressed into service. However, Johns was neither scraping nor measuring with this ruler. Instead he was drawing the process of drawing, creating a completely self-conscious artwork that refers to itself in image and in word. As a tautology, the visual and textual scrape is both a verb (an explanatory word, an action, and a command) and a noun (a picture, a result of an action, and a caption), describing what is happening, what we see, and what we read.

Akin to words within a language, which can be employed independently but are reliant upon their interrelatedness to create meaning, Johns’s No from 1964 and many of the drawings made after his paintings and sculptures operate simultaneously as hermetic works of art and as pieces fully woven within the context of Johns’s overall creative output.

1. Walter Hopps, “An Interview with Jasper Johns,” Artforum, 3 no. 6 (March 1965), included in Jasper Johns: Writings, Sketchbook Notes, Interviews, edited by Kirk Varnedoe and compiled by Christel Hollevoet (New York: The Museum of Modern Art and Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1996), 112.

2. David Shapiro, Jasper Johns: Drawings 1954-1984 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1984) 23. The italicized “after” appears in the original text.

3. from Johns’s sketchbook, Book A, p. 53, 1964, as reproduced as Plate 9 in Jasper Johns: Writings, Sketchbook Notes, Interviews.

4. Barbara Rose, “The Graphic Work of Jasper Johns, Part One,” Artforum (March 1970), 39-45 and “Part Two,” Artforum (September 1970), 65-74.

5. Johns is known for altering paintings even after they have been exhibited, as was the case with No from 1961. It is difficult to determine whether the painting we see today is dramatically different than when Johns first considered it completed.

6. Interestingly, both of the 1964 No drawings feature images of metric rulers with centimeter units rather than inches, which was more typical of Johns’s work at this time. This suggests that Johns worked from rulers available to him in Japan, where he made the drawings.

Jasper Johns Biography

N. Elizabeth Schlatter Biography