“Johns is consciously searching to discover every possible nuance of which a medium is capable.”

— Ruth E. Fine1

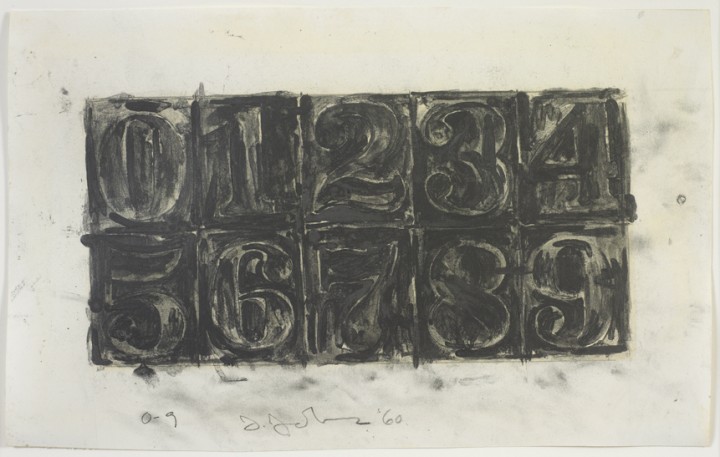

Jasper Johns is well known for his drawings and paintings of numbers. His works on paper 0-9 (1960) and Numbers (1996) provide two examples of Johns’s ability to make the medium part of the subject of his work. In 0-9, the two-by-five grid and sequential inclusion of numerals zero through nine emphasize the idea of a structured and closed set. The graphite wash employed in this work allowed Johns to create varying shades and to toy with the separation between figure and ground. Here, brushstrokes often play an integral part in defining the forms of the numerals and in directing one’s eye from one number to the next. Graphite dust is sprinkled noticeably on the paper surrounding the image. The visible juxtaposition in texture between the proper grid of numbers and these seemingly incidental, powdery smudges highlights the physical conversion of the dry graphite into a wet wash.

This conversion mimics both the shifting roles that numbers play in day-to-day life and the ways in which they function in Johns’s work. When written, numbers transform easily from abstract ideas to concrete symbols, thus relaying necessary information. Because Johns displays these numbers without any mathematic context or implied application, he demonstrates how numbers can further transition from symbols to graphic forms, designed for aesthetic contemplation.

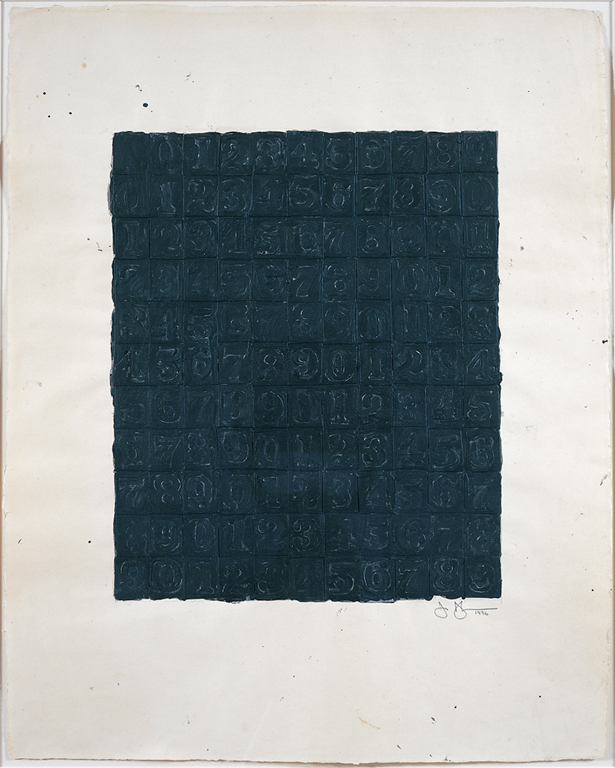

In Numbers, Johns created an expanded closed system of numbers by sequentially repeating twelve times the numerals zero through nine in an eleven-by-eleven grid. By leaving the first square of this grid blank, Johns allows the viewer to read the numbers in numerical order both horizontally and vertically. If read diagonally from upper left to lower right, the numbers are ordered by even and odd integers: 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 or 1, 3, 5, 7, 9. If read from upper right to lower left, the diagonal rows consist of identical numbers: all 9s or 8s or 7s, and so on. Despite this well-planned layout, the collage technique that Johns uses, which involves cutout squares and stenciled numbers, graphite, and acrylic, encourages the viewer to lose him- or herself in a multi-layered field of physical pattern with no particular hierarchy. Perhaps one might first notice the network of lighter areas in the dark paint surrounding the numbers, or another viewer might observe the work’s undulating surface, created through the uneven application of the grid’s individual collage units. A different set of eyes may be most engaged with the lumpy patterns caused by the inconsistency of the paint. The metered repetition of numbers here allows each viewer to examine, compare, and appreciate fully the visual subtleties of each unit.

In 0-9 and Numbers, Johns works with his medium in a way that physically mimics the intellectual process of understanding numbers. In both the transformation of dry graphite into wash and the physical layering of collaged pattern units, these works float between abstraction, representation, and aesthetics in much the same way that numbers do.

“But numbers exist only in the imagination. We write them every day, we use them all the time, but they remain stubbornly abstract in a peculiar way.” — Michael Crichton2

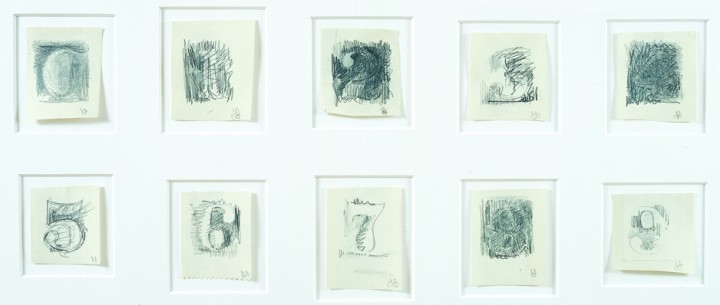

Jasper Johns’s decision to feature numbers—“things the mind already knows”—in his work has allowed him to expose the complex relationship between form and the perception of numbers. In Numbers from 1960, Johns transforms the ten individual digits from theoretical notions to concrete works on paper. In front of this piece, the viewer spends time reveling in the artist’s adept handling of the pencil and eraser, two of the simplest of artistic tools. Each numeral, ranging from zero to nine, exhibits unique line work; no two numbers look alike. In some instances, a number barely emerges into the foreground through a dense frenzy of crosshatched lines. In other instances, Johns has applied layers of fine lines that mimic a delicate concealing mesh. The contours of the numbers, while not always completely continuous, are often defined by a singular line, perhaps referencing Johns’s frequent use of stencils.

Never missing an opportunity to deepen the complexity of his work, Johns leaves the viewer to wonder how to understand Numbers. Should one view this array of numbers as a counting instrument, like a modern abacus? Should one merely read the figures as one would if they were located in a written text? Why did Johns opt to depict these numerals with such an expressionistic hand, rather than to employ the smooth contours and solid lines of handwritten or typed numbers? Perhaps the subject herein lies more in the beauty and possibility of the graphite line than in the coherent forms of the numbers themselves.

Johns’s use of scribbled lines, inside, around, and across the numerals’ borders, supports this reading. Far from careless marks, these lines reveal the rhythmic motion of Johns’s hand; almost as an afterthought, they also reinforce the shape of a number. The occasional erasures, still visible, prove that Johns carefully considered the effects this line work would have on the overall reading of the piece. It is this expressive line that unifies these ten small drawings. The inclusion of each digit, and their appearance in sequential order, allows viewers to do more than read the numbers exclusively as symbols. Here, one can also marvel at the network of lines used to portray these common figures and observe the artist’s complication of his subject.

1. Ruth E. Fine, “Making Marks” in Drawings of Jasper Johns, Nan Rosenthal and Ruth E. Fine (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1990), 53.

2. Michael Crichton, Jasper Johns (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994), 32.

Jasper Johns Biography