Before his untimely death at age thirty-one in 1979, Donald Evans painted almost four thousand stamps featuring an enormous variety of plants and animals, people, and landscapes. Miniature tokens of an imaginary world of astounding intricacy, Evans’s stamps represent forty-two make-believe countries from the around the globe. He made at least one issue of stamps for practically every year from 1852 to 1973, experimenting with every permutation of language, color, shape, repetition, variation, and abstraction that occurred to him. No stranger to philately (the study of stamps and postal history), Evans meticulously recorded the names, issue dates, countries of origin, and exhibition histories of his stamps in an omnibus that eventually stretched to more than three hundred pages. He called it the Catalogue of the World.

Evans was born in 1945 in Morristown, New Jersey. He started collecting stamps when he was about six years old. During the summer, he spent much of his time on the shores of a nearby lake, building all manner of structures of sand. Indoors, he constructed little villages out of Dinky Toys, plastic houses, and tiny cardboard boxes that he painted to look like buildings. In an effort to make these invented communities seem more real, Evans decided to make stamps for them. Drawing inspiration from the stamps in his collection, Evans had produced nearly 1,000 stamps from about forty different imaginary countries by the time he was fifteen.

Unsure about what to do upon entering high school, Evans thought about becoming an artist, although his interest in stamp making had subsided since adolescence. In 1963, he graduated and went to Cornell University, where he earned a degree in architecture in 1969. He moved to New York and got a job working for Richard Meier’s firm, where he proceeded to work on a number of prize-winning projects. He also began showing his childhood works to his friends. Their enthusiastic responses, combined with a growing dissatisfaction with the architectural profession, convinced Evans to become a professional artist. In the winter of 1972, he quit his job, packed up his watercolors, and flew to Holland to stay with a friend outside of Utrecht.

Once in the Netherlands, Evans began making stamps again–lots of them. In 1972 alone, he made 561 stamps from twenty invented countries. He always worked at actual stamp size, first sketching his designs with a pencil and then meticulously building up his stamps with watercolor and pen and ink. In a similarly painstaking fashion, Evans used the period key of a typewriter to produce the “perforation” lines of small, regularly placed black dots that surround his stamps. Throughout the next seven years, he would use his work as a kind of journal, recording and celebrating his own world. An inveterate traveler, he often named his imaginary countries after friends he had made or towns he had visited during his perambulations through Holland and the rest of Europe.

In addition to his watercolor paint set and #2 Grumbacher brush, Evans always traveled with a set of antique ivory and ebony dominos. He liked the way that they looked and sounded, so in 1973 he invented the Republic of Domino, a former French colony in which the game of dominos was both the national sport and the primary industry. Alongside his individual stamps, Evans created full sheets of stamps of a single value. Etat Domino Stamp Sheet (1973) features thirty-six three-franc stamps printed, Evans imagined, by the Imprimerie Dominoise (the Domino Printing Office) for the Etat Domino (Domino State) in 1938. Evans’s domino stamps and stamp sheets, in particular, represent some of the artist’s most abstract stamps. They possess a monotonous, serial organization reminiscent of work by Sol LeWitt or Donald Judd. To this abstract grid Evans appended the delicate shadows associated with ivory dominos; their subtle variability forms a charming complement to the severe regularity of the otherwise identical bricks.

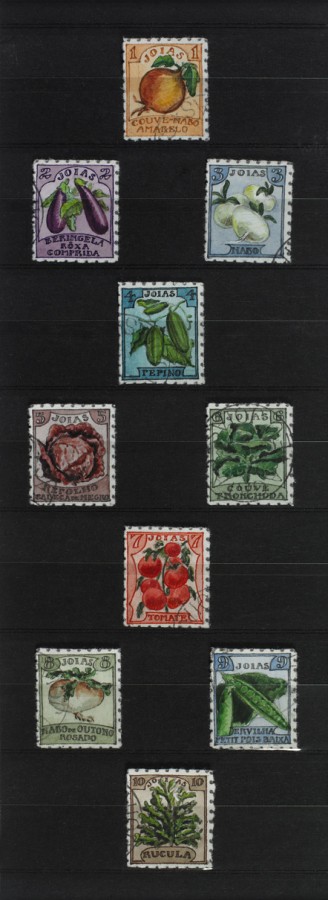

Evans’s Joias series of ten stamps (ca. 1975) takes its name from the Portuguese word for “jewelry,” and with their bright colors and astonishing detail, these stamps have an almost gem-like quality. Indeed, Evans’s depictions of red cabbage (Repolho) and spring greens (Couve) might be described as multifaceted, while his turnips (Nabo), tomatoes (Tomates), and peas (Ervilha Petit Pois Baixa) look like tiny vegetal diamonds, rubies, and emeralds. Evans often mounted his stamps on black paper because he valued the verisimilitude it added to the typewritten perforation lines that limn his stamps. Here, the black of the mount also serves to intensify the brilliance of Evans’s Iberian vegetables-cum-jewels.

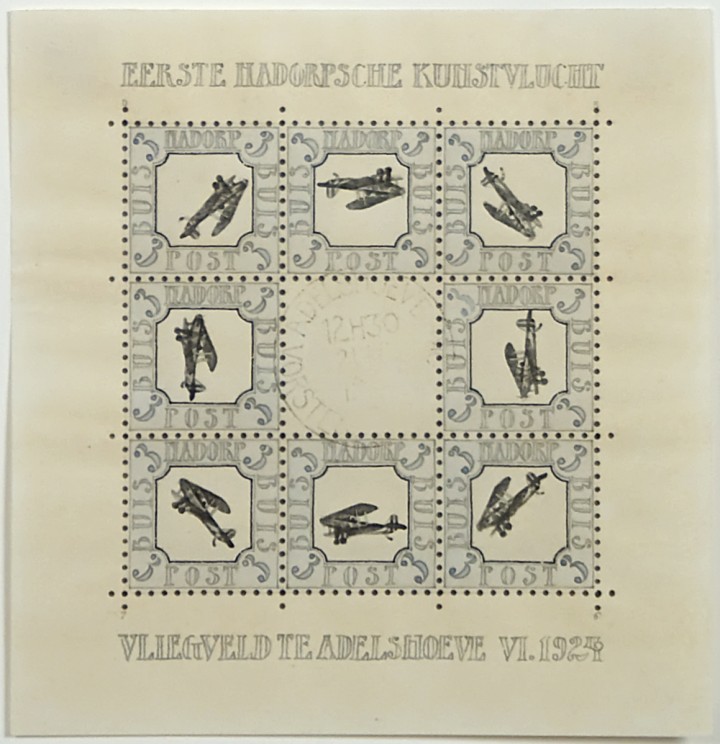

In colloquial Dutch, Nadorp means “After the Village.” It was also the surname of a friend of Evans’s whom the artist crowned as prince of this small Northern European country. Evans created a wide range of stamps for Nadorp, featuring typically Dutch subjects ranging from ships to windmills to the vegetables found in every country garden. He also created stamp series that celebrated the principality’s luchtpost (airmail service) based on photographs of early airplanes. Evans’s Nadorp 1924 Stunt Flying in souvenir sheet (1976) celebrates the first kunstvlucht (literally art flight, or stunt flight) in Nadorp. In the world of Evans’s stamps, the flight took place at the vliegveld (airfield) of Adelshoeve in the summer of 1924. To commemorate the occasion, Evans depicted a Blackburn Ripon biplane performing a loop-the-loop across eight stamps of a perforated sheet. To create the faintly visible cancellation mark in the center of the composition, Evans carved a unique rubber stamp using an X-Acto Knife.

In a 1975 interview, Evans explained, “I’ll cancel over the stamp to deliberately obscure things or just to be perverse, to establish a certain layer of distance from the work.” He continued, “To my knowledge there are no artists who make stamps the way I do. But there very well may be.”1 More than thirty years later, Evans’s art remains astounding, not only in terms of the intricate world it imagines, but also in terms of its distance from the 1970s New York art scene from which it emerged. Evans’s postal oeuvre, his Catalogue of the World, manages to be both comprehensive and singular.

1. Donald Evans, “A Portfolio of Stamps of the World,” Paris Review 62 (1975): 77. Willy Eisenhart’s 1980 monograph on the artist, The World of Donald Evans (New York: Harlin Quist), was also especially useful in the writing of this essay.

Donald Evans Biography