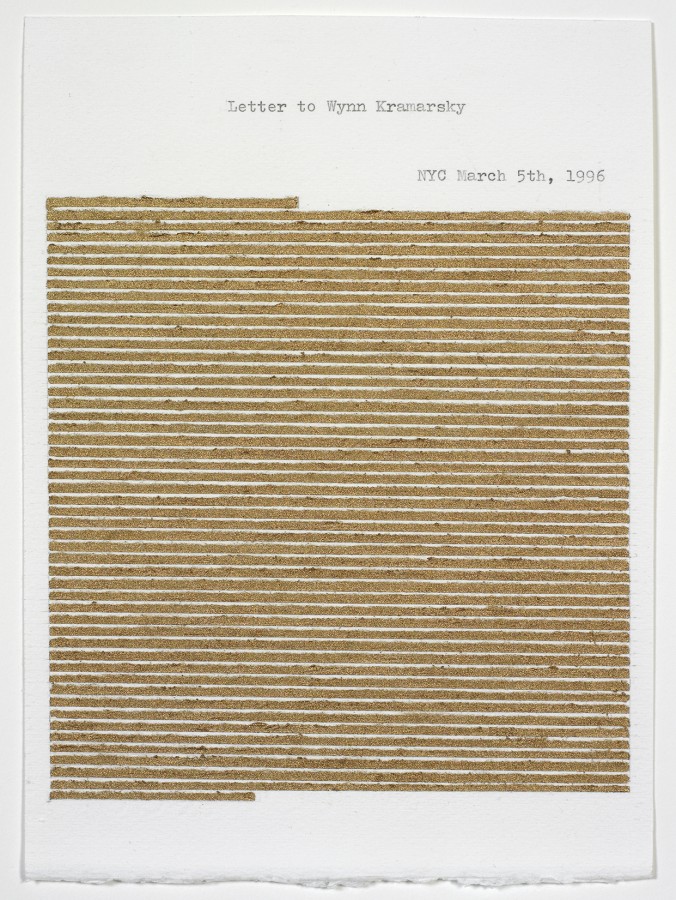

I’m interested this week in looking closely at artists who make a mark, then erase or cross it out. In this time and place of abundance, the purposeful act of removing, erasing, eliminating, crossing out, or discarding lines that have been drawn or written suggests any number of things. Are these instances of self-editing, thoughtful re-considerations, or a tantalizing tease? How does the act of erasing, concealing, or crossing out differ from an empty page or tabula rasa? How is the physical presence of that which once was different from that which has not yet become? A drawing or line of text that has been expressed and then removed leaves a trace that seems more poignant than the empty page. The temptation is always to try to read what has been excised, to reconstruct the drawing that has been erased, to imagine what lies beneath the censor’s black lines. It strikes me as I write that the physical memory of clarifying thoughts is lost to me as I delete and rewrite this text on a computer screen, not physically making marks on paper.

Rauschenberg famously erased a drawing by Willem de Kooning in 1953; it is now in the collection of SFMOMA. Through what the museum’s website describes as “digital capture and process technologies” the museum has discovered the erasures that de Kooning himself enacted in the process of creating the original drawing. How does erasure measure against mark making?

The artists I am thinking about are Bronlyn Jones, Elena del Rivero, John Waters, Jón Laxdal, Christine Hiebert, and Molly Springfield.

Donna Gustafson is the Andrew W. Mellon Liaison for Academic Programs & Curator at the Zimmerli Art Museum. She is also a member of the graduate faculty in the Department of Art History at Rutgers.