by Jonathan D. Katz

Why? I think I would rather be

a painter, but I am not. Well,

for instance, Mike Goldberg

is starting a painting. I drop in.

“Sit down and have a drink” he

says. I drink; we drink. I look

up. “You have SARDINES in it.”

“Yes, it needed something there.”

“Oh.” I go and the days go by

and I drop in again. The painting

is going on, and I go, and the days

go by. I drop in. The painting is

finished. “Where’s SARDINES?”

All that’s left is just

letters, “It was too much,” Mike says.

But me? One day I am thinking of

a color: orange. I write a line

about orange. Pretty soon it is a

whole page of words, not lines.

Then another page. There should be

so much more, not of orange, of

words, of how terrible orange is

and life. Days go by. It is even in

prose, I am a real poet. My poem

is finished and I haven’t mentioned

orange yet. It’s twelve poems, I call

it ORANGES. And one day in a gallery

I see Mike’s painting, called SARDINES.

— Frank O’Hara, “Why I Am Not a Painter”

Frank O’Hara’s poem “Why I Am Not a Painter,” perhaps the most celebrated meditation on the relationship of painting to language, turns on what’s shared in painting and writing and what isn’t. In the poem, the symmetry is made neat: a painting has the word “sardines” in it, while a poem is about the color orange. Most critical commentary turns on the way O’Hara’s 1957 poem underscores how far both successful poetry and painting can move from their initial conception, developing according to a medium-specific logic of their own. The painting by Michael Goldberg that O’Hara addresses in his poem ends up losing the image of sardines, retaining only the vague suggestion of these letters at the bottom of the image, while O’Hara’s twelve-poem suite, Oranges: 12 Pastorals, never even mentions that color in the body of the poems. Like distant echoes only partly heard, the poem seems to suggest, language reverberates through art, a palimpsest of lost thoughts and changed ideas.

The result is that, despite O’Hara’s protestations, the line between poetry and painting in both works begins to blur. O’Hara’s language evokes a series of mental images denoting color, form, and contrast ahead of any narrative arc — snot on a white linen field — images which in turn lend themselves to a painting concerned with the selfsame values. Language, in short, is liberated from utilitarian drudgery—telling us something—and assumes the conditions of abstract painting, in which significance is not a tidy package of meaning passed from speaker to receiver, but rather something intended to induce or conjure in the mind’s eye. All art, of course, can mean in manifold different ways, but the use of words in images explicitly turns the viewer into a reader as well, converting an ostensibly passive act into a very active one, underscoring how meanings are always the result of readings, of individual interpretive acts. We call this shift in emphasis away from the author and toward the reader as the maker of meaning “readerly,” as opposed to “writerly” art. So poetry, like painting, is readerly, in that it seeds thoughts that are not spoken, engages ideas it doesn’t narrate. Both painting and poetry work in the gap between the denotative and the connotative, in the space between the artist and the audience.

That space, because its meanings are quite precisely not spoken, not narrated, is an unruly space, a private space in a public forum. And because it’s private, it can call up or rouse thoughts and feelings that are not in accordance with dominant narratives, not acceptable thoughts. In fact, it can serve to educe a self at war with one’s public self: that private self that exists in all of us, watching the public self perform identity and putting the brakes on if things get out of hand. Art and poetry, both, can thereby achieve the remarkable prospect of opening a space wherein meanings consonant with the demands of the mainstream meet and occasionally fall down before a range of other interpretations that are actively suppressed or policed. And that’s my point: that words became a newly popular vehicle in the visual art of the Cold War era precisely because, during the constrained and anxious socio-political context of the Red and Lavender Scares, a political moment in which dissent was deemed unpatriotic and calls for social justice were aligned with treason, art and language’s inbuilt multivalence, their ability to carry different, even contradictory, meanings at once, created a place for individual acts of ant-conformist thinking, private flirtations with ideas unauthorized by then dominant socio-political realities. From the artist’s perspective, words in art offered a permanent alibi. If one was understood as having said something one shouldn’t have, it was entirely plausible to say that any such meaning was a product of the reader’s interpretation, not the artist’s intent. But even more significantly, words allowed an artist to seed the work with multiple, sometimes conflicting, significances, to figuratively speak out of both sides of the mouth. Artists who used words in their art repeatedly claimed that any resulting interpretations belonged wholly to the viewer, not to the artist. “Meaning belongs to the people,” is how Robert Rauschenberg phrased it.

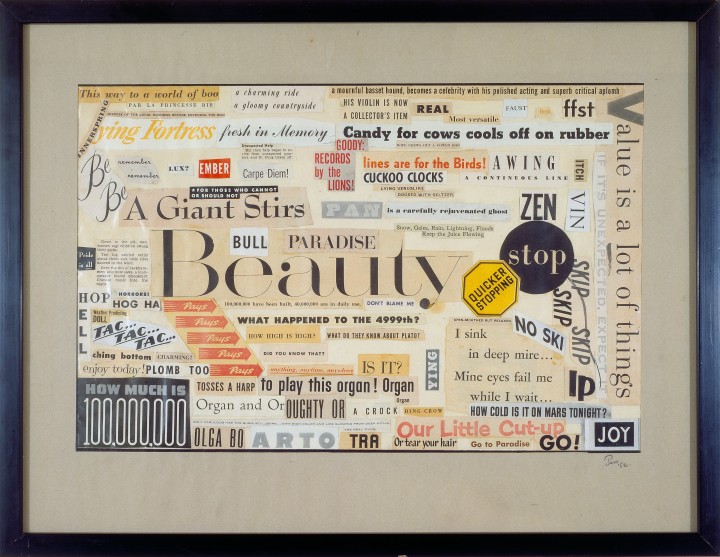

This decentering of meaning from the artist to the audience was, if anything, even more instrumentalized in the work of queer artists. It should perhaps come as no surprise that the leading figures in the renaissance of words in post-war American art were, like Frank O’Hara himself, initially almost exclusively homosexual. Queers had long deployed an encoded form of speech, taking advantage of the multiple shadings of common words to carry queer meanings under the very noses of a hostile public. Camp, as a species of this process, extended this embedding of contradictory significances into familiar forms of inversion such that, for example, men became ladies, and women butches. Here speech acts become a form of political engagement with the world, and language a weapon of social liberation in a context of grave political constraint. No wonder queer artists such as Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Jess, Ray Johnson, John Cage, and Robert Indiana each made the deployment of language central to their practice at this time. And for each of them, words worked in art in part as a means of at once multiplying and thus de-authorizing normative meanings, making evident the multiplicity of readings always attendant upon viewing art.

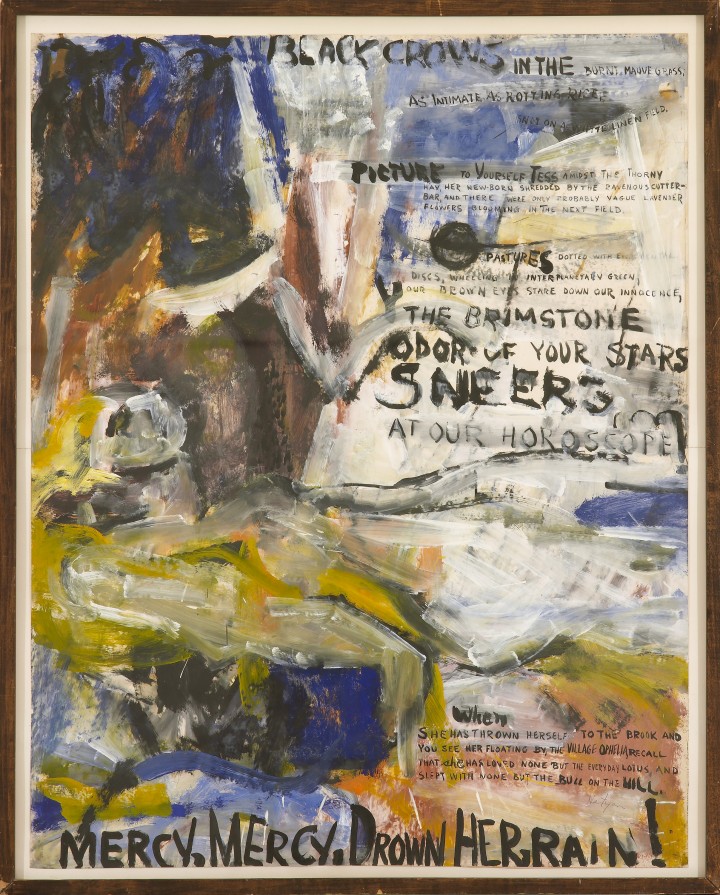

Yet even in the carefully constructed environment of language in the visual arts, the meanings of words, phrases, even whole sentences will differ depending on the viewer. Let’s return to Hartigan’s Black Crows (Oranges No. 1). While all of us can see the horizontal woman reclining in the bottom third of the picture—at least once it’s pointed out (you see her floating by, the village Ophelia)—seeing it doesn’t make it emerge; only words can do that, calling forth this abstracted supine blonde woman into existence the moment I name and categorize her. Yet the very lines from O’Hara’s “Oranges No.1” that Hartigan quotes above the supine form (Picture to yourself Tess amidst the thorny hay / her new-born shredded by the ravenous cutter- / bar, and there were only probably vague lavender / flowers blooming in the next field.) not only set up a mental picture, but pace it, opposing the intimations of heedless violence in the first part of the sentence with the leisurely, wandering intonations in the second. The point is that we often see what’s in front of our faces less well than what we imagine in the mind’s eye. Language thus retains a certain priority, even in the act of seeing, and Oranges can still be somehow about the color orange (or the fruit—there are, after all, a dozen “Oranges” in the suite) even when that word is never used, and Goldberg’s painting is called Sardines even when “All that’s left is just letters.”

This Duchampian notion, that the mind sees as well as, or better than, the eyes, was one that quickly came to define an enormous share of post-war art, for it was a valuable shortcut toward an art that distrusted the appearance of things. And no formal device was more anti-appearance than language. That distrust in appearance, the idea that sight was insincere and that knowledge required piercing the veil of the visible, would only grow stronger as the ‘50s became the ‘60s and beyond. Now we can’t even trust the once-sacrosanct photograph to tell us the truth of things, for the visible is so easily manipulated. But long before computers manipulated appearance, various ideologies deployed images to achieve the same kind of propagandistic manipulation: Clement Greenberg’s famous essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” specifically called out Soviet agitprop in this regard as early as 1939, and Surrealism, to name just one art movement, counted on the lie of appearance for the lion’s share of its effects. As we grew to increasingly doubt that we could trust what we saw, language assumed an ever more particular role in our art. The very specific social conditions that led homosexual artists to redeploy language in art in the post-war world quickly came to serve other artists for other purposes. But no matter the artist and era, when words enter the picture, the fluid, utilitarian transparency of language slows to a halt, meaning eddies, and words begin to clot and scab, dotting the surface of art. And like all scabs, these newly visible words cover a wound.