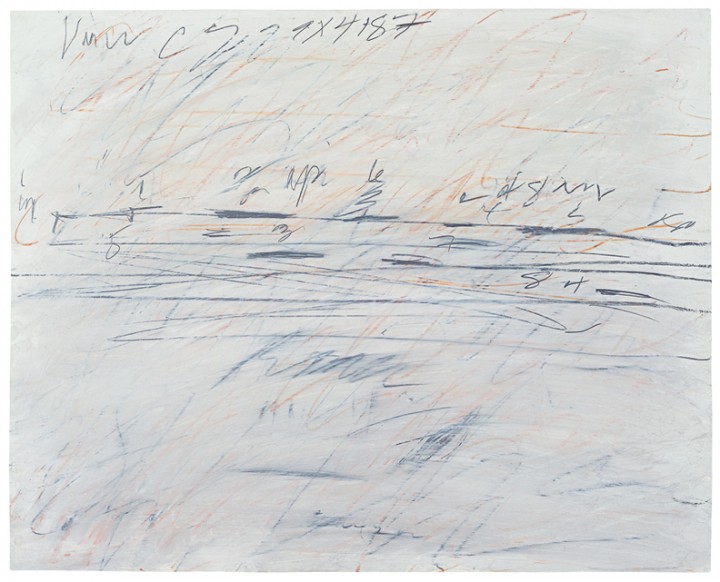

Cy Twombly’s genius as an artist lies in creating intuitive, emotional forms that investigate both the process of drawing and its relationship with writing and language. His work often incorporates textual references to Greek and Roman mythology and engages the techniques of Surrealist-inspired automatic writing, through which Twombly studies the physical act of mark making. Individual characters, words, or phrases can occasionally be extrapolated from within the fury of Twombly’s dynamic line, yet in Untitled (1971) it is difficult to decipher precisely his scrawling notations. When viewing the drawing, one can pick out the numbers 8 and 4; here and there an X or a C rise to surface. Is that the letter P and the word of or up? Can we make out the word lightly smeared across the center of the paper? As with much of Twombly’s early work, here too it is impossible to avoid searching for recognizable letters or trying to make out the coded language he seems to convey. Because Untitled does feature some identifiable characters, it is only natural for the viewer to read these markings as signifiers of language and thus innately to assign meaning to the image.

Untitled is related to Twombly’s “Treatise on the Veil” paintings, a series of works made between 1966 and 1971, which feature broad grey-ground planes spanned with marks resembling either mathematical measurements or musical notation. As a sort of study after his larger “Veil” paintings, Twombly included some of the same cryptic markings in Untitled. How did Twombly intend these works to be deciphered? Did he intend his works to be understood at all? Does his inclusion of familiar characters and letters imply that the viewer must interpret the drawing as one would a text? Perhaps the viewer is meant to explore Twombly’s writing as just another form of mark making, like hatch marks in an engraving or brushstrokes in a painting. The marks in Untitled are not necessarily meant to be read concretely, but rather provide an opportunity to explore the intricacies of language and the very process by which we associate meaning with the written word.

As John Berger writes of Twombly’s work: “[His] paintings are for me landscapes of this foreign and yet familiar terrain. Some of them appear to be laid out under a blinding noon sun, others have been found by touch at night. In neither case can any dictionary of words be referred to, for the light does not allow it. Here in these mysterious paintings we have to rely upon other accuracies: accuracies of tact, of longing, of loss, of expectation.”1 Indeed, Twombly’s work is not clear or legible; the mystery of his mark making affords viewers the opportunity to examine their individual relationships with language.

1. John Berger, “Post-Scriptum” in Audible Silence: Cy Twombly at Daros, eds. Eva Keller and Regula Malin (Zürich: Scalo Publishers, 2002).

Cy Twombly Biography